The Pools Beneath a Guillotine: A Review of Comemadre

21.12.18

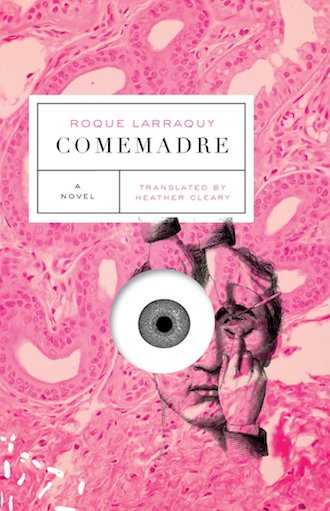

Comemadre

Comemadre

by Roque Larraquy

Translated by Heather Cleary

Coffee House Press

152 pp. / $16.95

Comemadre by Roque Larraquy, translated by Heather Cleary for Coffee House Press, tells a story of bawd and the limits of experiment.

The plot follows a group of doctors in a sanatorium in Temperley in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1907. A vain and judging doctor, Quintana, voices the narration for the first half of the novel. He mocks his coworkers, holds no quarter for their simpering affectations, while secretly suffering in many of the same ways. He fantasizes about Menéndez, the head nurse at the sanatorium, much loved by all the doctors, and the object of Quintana’s secret desire.

The action begins with a sinister proposition, upon learning that a decapitated head remains alive for nine seconds, one Doctor Ledesma suggests, “If we could corroborate it scientifically, we’d be answering a great many questions. We’d be exploring territory that has, until now, belonged exclusively to religion: what is death and what comes after death.”

“This is what I propose,” he continues: “We select a group of terminally ill patients and sever their heads without damaging their vocal apparatus…We then ask the heads to tell us what they observe.”

It’s a silly proposition, with all of the inevitable gore of a camp horror film. The novel’s charm comes in the mundane college novelesque vying for position of the doctors. They begin to do terrible things, worrying mostly about the logistics. Many of the best jokes have to do with Quintana’s incompetent attempts to woo Menendez, not to mention the foolhardy, “Argentine National Character.” In tenor, it reminds me of certain dark comedy films by Chabrol or Zulawski, films that are ostensibly thrillers, but are actually comedies of manners.

The overall mood is wise cracking and self-aware. There is a thread of modernism that centers wholly on institutes and hospitals. For people from the early 20th Century, the pettiness and systems of control that came to symbolize an emergent world. It’s evident in Franz Kafka, and Maurice Blanchot. Jakob von Gunten, the 1909 novel by Robert Walser, imagines an institute for servants. Walser lived out most of his adult life in a sanatorium. Thomas Mann’s 1924 masterpiece, The Magic Mountain, takes place in a sanatorium in the mountains of Switzerland. Antonin Artaud famously experienced hallucinations, living in asylums until his death. So this is, of course, a tongue-in-cheek evocation of high modernism.

The second half of the title wades into some common themes. There is an uncanny double. The art of the decomposing organism is highlighted, recalling Peter Greenaway’s bravura A Zed and Two Noughts, and some cliché thematic material on an enfant terrible of conceptual art.

And its familiarity with these tropes again allows Larraquay to focus on the style of storytelling.

Wit is almost priceless in literature, it makes any novel buoyant. Comemadre has wit in excess, spilling out over the pages, like an army of red ants, or the pools beneath a guillotine.

There’s a 1945 Three Stooges horror parody called: If a Body Meets a Body, complete with floating skulls, murdering butlers, and yes, dead bodies. In Larraquary’s text, “Comemadre” is the name of the flesh eating plant the doctors use to dispatch bodies. As you might imagine, it makes quick work of the corpses.

But in the afterglow, the information aura sticks around, to everyone’s dismay. The doctors and the artists, every character does horrible things, with little apparent incentive. So the best part of the book has to do with weak people being petty and jealous and mean to one another, forging a terrifically funny read. The action is all violence and humor without moralizing. And just maybe the meanness is the message, because like with Moe, Larry, and Curly, physical humor has an element of the embodied, and the many brain deaths of the Stooges mirror the inevitable critique in Comemadre of 19th century phrenology that localizes thinking or even the soul inside the head.

As the Three Stooges say, it’s ok if you have brains, just don’t let them get to your head. Bawdiness, lusty physical humor all emphasizes humans as thinking through bodies and the exchange of body experiences. Comemadre drives this home, and begins to explore the paradoxical way that after the bodies disappear, the thinking passes on in a hysterical danse macabre.