TALKING TO HIMSELF: On Lars von Trier’s The Five Obstructions

13.04.15

If there was ever a well-meaning, fallible filmmaker who just could not find the right human being to talk to, it would be Lars von Trier. I am both riveted and horrified by his films. I think he’s a genius with a camera. But, by God, he’s the absolute king of digging out someone’s heart with a coffee spoon and making a complete bloody mess of it. You won’t hear me admit much sympathy for Lars, but I must say, I think that is a very lonely, frustrating thing. Imagine, wanting to share feelings with someone all your life and always turning it into a bloody mess—and not only that, but in so doing making everyone think you’re a complete asshole.

I don’t think Lars is a complete asshole, and neither do I think he is misunderstood. I think he’s just Lars, as fallible and in need of love as any of us, and maybe a little too oafish in imposing his will on others. I feel privileged to make all these rather excessive statements about the personal life of a man I’ve never met because Lars once dramatized these shortcomings in a film about friendships and conversations. It was a very good film, in fact, one of my favorite of his. It is called The Five Obstructions.

The basis of the film is Lars’ idea: “I’m going to help Jørgen Leth.” I don’t know exactly why Lars thinks Jørgen needs his help; the film never makes it clear what he thinks is Jørgen’s problem, nor why he’s the one to solve it, but it seems to have something to do with Jørgen’s inability to be honest with himself about who he is, and Lars’s pathological need to tell everyone—himself included—just what’s wrong with them. He tends to do this by picking on them with insult after insult until they’re forced to scream out the truth.

Jørgen is Lars’s cinematic mentor. He’s the creator of a short film called “The Perfect Human” that Lars has seen some 20 times and that he claims to love. Lars’s way to help Jørgen is by challenging him to remake “The Perfect Human” five times. He’s going to have a conversation with Jørgen through this process. The truth-inducing insult he’ll deliver is that he gets to impose whatever ridiculous conditions he wants on Jørgen’s remakes. These challenges are going to get his mentor to reach some catharsis—although no matter how many times I watch The Five Obstructions I never really get what Lars expects to happen after that. Is catharsis just an end of its own? Is this a prelude to some kind of healing? Or maybe it’s just Lars’s ego running amok again.

Lars’ little project always reminds me of “The Hunger Artist,” Kafka’s infamous story about a man whose art is in starving himself. He just sits in a cage and doesn’t eat anything, and the people who watch him find some kind of beauty in it. This is art. Absurd as it is, this is art. It’s popular to think of art as this potted flower that must be nurtured with unceasing enthusiasm and Guggenheim fellowships, but Kafka tells us that art isn’t so fragile. You couldn’t kill your art if you wanted to. To the contrary—your art is precisely what kills you. You can’t even really share it with anyone: it’s is a lonely little cage that people watch you through.

I’m inclined to go with Kafka on this one, because I’ve not yet found anyone who understood art better than he. I’m big enough to grant you your own idea of it, but I will always side with those who feel the ache of Kafka’s hunger. I’ve found this ache to be good for very little else, except perhaps for instilling a demented drive toward truth at all costs. I’d say Lars feels this drive too much. He’d certainly be much happier if he didn’t have to feed his hunger, but I don’t think that’s an option. No, I’d say his best option is the one Sigmund Freud offered us: art as psychotherapy. It wasn’t the flower that we currently patronize it as, and it wasn’t Kafka’s tapeworm either, it was something more like a mirror for peering into your soul. Art as therapy. No. Art as dialectic. Better. Art as conversation.

The Five Obstructions begins by shoving you right into the midst of Lars and Jørgen’s conversation. There’s Jørgen with his hair oddly short and those two ever so slightly bucked front teeth that pop out like flags whenever he smiles. There’s Lars, head shaved, little pockets of stubble oddly dispersed around his face, looking like the kind of person he would cast as an Eastern European criminal. The camera is tight on them, the angles are all skewed, there are all kinds of miscellaneous junk in the background. This is the cinematic equivalent of that mess of stereo cables in your living room that you keep trying to hide when you have people over.

In other words, it’s a Dogme95 film. This is what I love about Lars—only someone of Lars’ sensibility could have come up with Dogme95. And that’s because he doesn’t try to hide the shit. You know the shit exists, I know the shit exists, Lars certainly knows the shit exists. So okay. Let’s stop trying to pretend it’s not there, and let’s talk about it.

And what a glorious way to talk about shit: we’re going to remake “The Perfect Human” five times, says Lars, with a little mischievous look on his face. I’ve never really figured out why Lars loves “The Perfect Human” so much. This is a bizarre, 17-minute film that Jørgen made in 1967, a kind of pseudo-documentary where he films the “perfect” man and the “perfect” woman doing everyday things like trimming their nails and brushing their hair and walking around their infinite little room. There’s a voice-over where the narrator makes naïve remarks regarding his curiosity toward their perfect nature, talking as if they’re caged animals. The set is spotlessly white, and the “perfect” man and “perfect” woman are all-around embodiments of not-a-spot-of-lint-ness. Every time I watch the film, it makes me think of a very well-tended, very, very clean mental hospital.

As Lars and Jørgen watch the film on Lars’ sad little television set, you have to ask yourself, What exactly makes Claus Nissen the perfect man? One day as I watched him dancing around in a tuxedo against a background white as infinity, it hit me: he’s annoying as hell. He’s just dancing around the frame with some hip little sunglasses on, smiling at me like he knows something I’ll never figure out, clearly aware that the camera is on him and not on me, because the camera is drawn to beauty and symmetry and normalcy, and he knows that he’s all those things and I’m not. He’s perfect because he’s just happy to be dancing there, perfectly inhabiting his body with a satisfaction that only the gods and movie actors could ever know. And this complete satisfaction with the fact of being oneself is hugely, hugely annoying—this is just what being the perfect human is. I want to punch him in the face. I bet Lars would like to punch Claus Nissen in the face too.

Lars and Jørgen are not perfect humans. They don’t inhabit a perfect white, infinite room, they inhabit Lars’ disheveled little workspace where he keeps pouring himself more white wine and it’s obvious he still has a drinking problem. Jørgen and Lars are both depressives who have done a lot of bad things in the name of themselves, and they’ll probably keep doing somewhat bad things all their lives. Lars in particular seems like he’d be a handful. For one thing, he can’t stop talking about everything he thinks is wrong with himself. He’s one of those people who turn trauma into a heroic personal attribute and just shove it up your nose until you can’t breathe. Jørgen on the other hand is that monolith of a friend whose psychological depths you’re never going to tap. I can see the grey in their hair, but the mannerisms and behavior are that of boys. Overgrown boys. These boys certainly have personality issues, and they’re essentially feeding their egos in making a movie about themselves making movies, but out of all these bits and scraps of self-indulgence comes something truly interesting, and interesting to watch. One begins to get a sense of why artists are driven to make art, and why any non-artist should give a damn about what they make.

With obvious relish Lars lays out the first set of obstructions:

1. No edit will be longer than 12 frames.

2. Jørgen will answer meaningless rhetorical questions he posed in the original film.

3. It will be shot in Cuba.

4. Jørgen will not be permitted to build a set.

The idea of constraint in art is by now a rather old glove. It received its full due in ’60s France—an unrestrained place if ever there was one—where a group of writers, of male writers mind you (Dogme95 is a little boys’ club too), got together and decided to form a treehouse that they were going to call the Ouvroir de littérature potentielle. And what were to be the tools in this workshop? Constraints. Weird little rules that they set themselves before writing. By far the best-known of these is Georges Perec’s injunction against himself to ever use the letter e in his book La Disparition, which he then wrote as an existential fairy tale about a search for the missing “Anton Vowl.” Lars reportedly made his own workshop of potential films in just 25 minutes. He said he couldn’t stop laughing the whole time. And at the end of that humorous half-hour he had a “vow of chastity” restricting filmmakers to a series of rules, mostly to do with limiting the scope and technology of the project: filming must be done on location; props and sets must not be brought in; only diegetic sound; handheld cameras; no special lighting; etc.

Dogme95 is a kind of banalization of art, a limiting of its means until what is most likely to come out is crap. (I’ve watched plenty of Dogme95 films and can verify this.) Even when Lars isn’t shooting per Dogme95 standards, he still goes out of his way to make his films ugly and unnecessarily restricted and downright banal. But what comes from this method—at least in his hands—isn’t crap. Or rather, it is and it isn’t. The Modernist art movement was largely a movement based on discovering the aesthetic potential of crap. So, obviously, Duchamp sticking a urinal on a pedestal and calling it art. And ever since that day, Modernist art has been dogged by people with no sense of humor decrying it for trying to explore the banal. Thus the guy who sneers at a Jackson Pollock because his son could have made it. Incidentally, you have to understand that when I use the word crap here, I’m using it in a very broad sense, everything from the trash that gets taken away every Wednesday to the kitsch sitting on grandmother’s shelves to all those sharp little unwanted thoughts embedded just behind my eyes. This is the subject that the Modernists chose to explore—and why wouldn’t they? There’s no single thing the modern world has produced in such abundance as crap. The production, consumption, and disposal of crap is the purpose of capitalism. All this crap that sits beneath capitalism is the very submerged iceberg of our way of life, and if there’s one thing Lars has proven his interest in, it’s forcing this truth into the light. His very career as a filmmaker has been a terminal drive deeper and deeper into that immense mound of crap we live atop. And in doing this, Lars is being pathologically honest about us. We all have crap, we all have it in essentially the same few complexes, we all medicate it with the same few substances and activities. It is the lingua franca of our culture, and it is precisely what Lars is trying to make this film—every film—about.

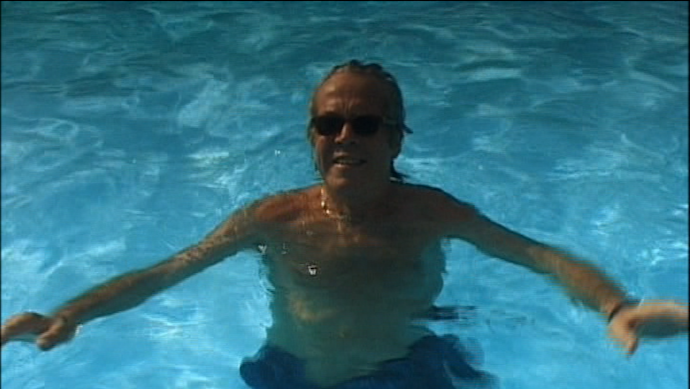

So Lars is saying to Jørgen, Let’s try to explore all that crap in your head, and Jørgen is saying right back, No. My favorite scene from the making of this first remake comes when Jørgen is treading water in the pool in his Havana hotel. It’s a very brief shot, just long enough for Jørgen to utter the following words: “twelve frames are a paper tiger.” This shot is the mate of one that occurs about ten minutes earlier, when Lars lays down the 12-frame obstruction and we see a shot of Jørgen’s face where it looks like that cigar he’s smoking just went in the wrong end. But now Jørgen conquers Lars, and here, for just a moment, he inhabits that pool just as he is meant to inhabit it, like an actor who has finally come to live his role on screen. This is perfection, and Jørgen obviously loves it. I do not, and nor do I think does Lars, either. When I have known this feeling it’s filled me with dread. I envision it now as a sharp, tiny ledge pitched atop an enormous pyramid.

A few things you might not know about Lars: he’s so afraid of flying that he’s never been to the United States, despite making two films set in it, and very critical of it; for years he drove from Denmark to France for Cannes, until, in 2011, after he said he expressed sympathy for Hitler, he was banned indefinitely from the festival; he’s filmed live sex in a number of “female-friendly” porn films he made in the late ‘90s, which reportedly led Norway to legalize pornography in 2006; he has a way of making actors declare that they’ll never make another movie after they’ve worked with him; his parents were nudists and took him to nudist camps.

They also didn’t believe in setting rules for children.

Jørgen’s first film is fantastic and Lars is dumbfounded by how damn good it is. He tells Jørgen, “One always feels furious when it turns out there are solutions.” He gives him caviar and vodka and tells him he’s been waiting all morning to get into the vodka. Always before noon, jokes Jørgen as he takes a sip.

It’s here that Lars reveals to Jørgen his secret agenda, that these obstructions are meant to be therapy. Lars doesn’t give a damn about Jørgen making good films. Point blank he says he wants him to make “crap.”

“I want to banalize you,” he says.

If you watch Lars’s films, you’ll see that he loves the idea of ruining oneself as a way to understand one’s demons. Lars himself has been in and out of therapy for years. At least since his second film, 1987’s Epidemic, he’s explicitly said he makes films to cure his depression, and virtually everything since could be considered as a very brutal kind of autopsychoanalysis. Lars knows he’ll never be a normal, moderately happy human, so he makes a farce of the pursuit for normalcy. Almost as a challenge, in each film he bears right down on the banal, and inevitably he always ends up swerving into the sublime. This is Lars’s particular genius as a filmmaker, and this is precisely what he plans on The Five Obstructions being for Jørgen. The very perfection of Jørgen’s art is hurting Jørgen—the only way to help him is to force him to ruin it.

For the second obstruction, Lars tells Jørgen to make a film somewhere where he’ll feel completely uncomfortable. As an example, Lars says Jørgen might ironize a dying child in a refugee camp.

I’m not that perverse, replies Jørgen. Like you, I can hear him add.

The essence of it: Lars wants to get Jørgen to do something that he’s never going to do. As the men haggle over this thing Lars is going to get Jørgen to do one way or another, the next set of obstructions come out:

1. Go into the most miserable place you can think of

2. Don’t show that place in your film

3. Jørgen has to play the perfect human in this location

4. The scene he will remake is the meal scene

Lars is getting personal with this second set of obstructions. The first four were all obstructions in the sense of hurdles: they were meant to make it physically difficult for Jørgen to complete his task. But these are of a different order entirely—they’re mindfucks. This is a subject Lars excels at to a rare degree. My guess is that he can’t help but fuck with the minds of people he’s close to.

I, for one, would not want Lars trying to fuck with my mind.

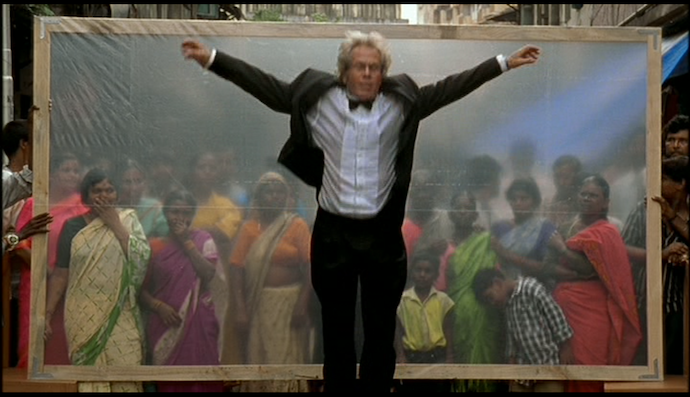

Jørgen’s second film is a cop-out: he eats the fish dinner with a transparent screen behind him, beyond which you can see vaguely impoverished Indian citizens looking confused and somewhat bored. This is a complete dismissal of Lars’ second rule—don’t show it. Lars’ idea was that Jørgen was going to go and soak up the misery of this place he had sentenced himself to, and then he was going to sublimate it through his consumption of the meal, and it was going to be some godawful Jørgen-style trainwreck. But Jørgen won’t let so much of a breath of air inside of him, certainly not the pain and suffering of complete strangers, so instead we see a bunch of confused people through a screen, and Jørgen never gives any indication that he even realizes that they’re there. It’s another perfectly acceptable film, real capital-A Art, and Lars is incensed because it means that once again Jørgen hasn’t so much as flirted with banality. What I would say he’s done, what he does with each of the six perfect humans, is he skims the smooth surface of art. He handles this film as coolly and efficiently as he’s probably handled every last thing in his life. But still, Jørgen shows us something here, perhaps without realizing it: that screen is how he sees the world. It’s the distance between him and Lars, between him and those Indians, between him and every other thing on Earth. Lars is right: the man has placed a tiny little perimeter of infinity all around him. You can see it every time those two big front teeth emerge in one of his impenetrable smiles.

After they watch the second remake Lars is very displeased with Jørgen. He goes from playing the loving God to the vengeful one. I get the idea this is something that happens a lot with Lars. People who place themselves under Lars’ direction somehow transgress the rules he has constructed for them and—boom! Vengeful Lars. Just like the Christian God, Lars’s punishment for Jørgen comes in the form of a choice: either go back to Bombay and remake the film the way I told you, or make a film with no strings attached whatsoever.

Jørgen looks aghast: “I’d rather have something to hang on to.”

We subsequently see Jørgen walking around a hotel in Brussels, the simple predicament of being unable to find one’s room turned into a claustrophobic, existential dilemma. I’ll bet anything that Lars cut this scene because this is so utterly Lars: making a dull little predicament that everyone has been through at least once into a vertigo. There’s a great shot of Jørgen staring out to the left of the frame while, behind him, a hotel corridor drifts off in rectilinear perspective. This is exactly the corridor toward our self that none of us will ever finish traveling, the corridor toward the truth that Lars traverses untiringly. But you see, Jørgen is staring out away from it, not the least bit interested in traveling down it.

The crazy thing about film number three is that it stars, as the perfect human, a 65-year-old Patrick Bauchau, 36 years after he stared in Eric Rohmer’s film, La Collectionneuse. I absolutely love La Collectionneuse. And Jørgen loves it too. He calls it “Rohmer’s most important film.” Whatever does he mean by that? Could it be that deep within Jørgen’s cold Nordic heart he really does believe in romanticism? Or maybe he just found the disturbingly pre-pubescent body of a 20-year-old Haydée Politoff . . . inspiring. The truth is that Jørgen has fucked lots of suspiciously young women in all kinds of Third World locales. He even, at the ripe old age of 73, made a film about it called The Erotic Man.

It was not received well. Although as Jørgen noted rather enthusiastically on his blog, the “very satisfying premiere” featured “no walk-outs!”

But anyway, Patrick Bauchau. Now this is a strange choice. Claus Nissen was a sweet doddering oaf who took a child-like satisfaction in doing things like smoking a pipe, tying his shoes, and walking back and forth. I don’t think Patrick Bauchau would be caught dead smoking a pipe instead of a cigarette, but if he did he certainly wouldn’t be capable of putting that pipe in his mouth without making it into a sexual proposition. Perfect human version Patrick Bauchau is a sexually predatory, elegant macho trotting around with a gun in his briefcase. Perfect human version Claus Nissen is an asexual manboy in a little white sanatorium, chaste as a Ken doll, and if you took of his perfect pants I doubt there’d be much to see.

“Not a mark has been left on you,” says Lars to Jørgen, and Jørgen looks back at him with a rich, disdainful smile. You can almost hear him saying, what crap, Lars, what godawful nonsense. Jørgen wants nothing of the kind of emotional vivisection Lars does by pure instinct; it freaks him the fuck out. What Jørgen does well is, he gives the appearance of doing what Lars actually does. Lars tells him to go root through the crap, and each time Jørgen makes something perfect in its hermeticism. Impermeability is Jørgen’s image of perfection, an impermeability that you’ve convinced yourself is more than porous enough. And this, really, this is Jørgen’s inability to ever so much as flirt with the banal, because Jørgen is not a man of pores, he’s a man of sleek, smooth surfaces. It’s all in there, by God, every last thing you would ever want to know is there, but you have to be willing to push as hard as Lars does to break through. Jørgen is content with making a mockery of the whole venture.

I must admit, my own innate sympathies will always be with dead-end truth-tellers like Lars, because I’ve lived my life with that ache for self-knowledge. I have no idea what I’m here for if not to feel this ache, as fatuous a life as that may seem. My ache is surely banal to anybody who doesn’t feel it, but it is mine, it’s my hunger, it’s the only thing I have to feed. And so I do it. I see quite well why Lars cannot stand Jørgen’s impermeability, it must be said, our good Jørgen is being a good sport. He’s giving Lars his chest to try and dig into, it’s just that Lars keeps failing. Far better to have such shameless honesty than to have to deal with those who contrive a false hunger from baroque language and empty erudition.

One feels bad for Lars, trying to force this into Jørgen, even as it’s becoming clear that Jørgen’s getting bored with the whole thing. He wants to see those last crumbs forced out, he tells Jørgen, those last things that no one wants. Yeah, yeah, says Jørgen. I want you to feel like a turtle on his back, advises Lars. Right, turtle, says Jørgen, let me write that down.

I’m going to make a very, very, very, very simple rule for the next obstruction says Lars. And I can’t imagine it’ll be anything but crap.

The fourth obstruction is that Jørgen must make a cartoon.

Both men make it clear that they despise cartoons.

Lars has gone all out. This is total war. Crap, by any means necessary.

“I think it’s an interesting exercise, actually,” Jørgen says, safely ensconced in his beloved Haiti. What confidence. You can see that he’s already figured out how to impose that distance, to once again get beyond the frame of his own creation and become the cool, detached observer. Jørgen is perfect. Lars is fucked. Jørgen hasn’t even made the fourth film yet, but it’s clear that he’s discovered how to impose a masterful defense that Lars will never breach. The game is over.

What Jørgen does for this fourth film, and I think this is complete cheating, what Jørgen does is to hire a cartoonist living in Texas to do all the work for him. Jørgen just tells him what he likes and what he doesn’t. We can’t help looking for a solution that satisfies us, says Jørgen. A solution to a problem. This is Jørgen’s approach, and this is why Lars has such a hard time with this conversation he’s trying to have with Jørgen: he’s not interested in truths, he’s interested in solving problems.

This fourth movie is a mélange of Jørgen’s first three remakes, plus the original perfect human. Finally, we can’t help but notice something that has been going on the entire movie: these films are becoming more and more self-referential. And this makes sense, because with each new set of obstructions Lars has been digging ever deeper with his insults, Jørgen digging ever deeper into a defense. His defense is brilliant: rather than let the insult force its way into himself, Jørgen is deflecting it into the film they are co-creating. In other words, if this film is a conversation, then the conversation between Lars and Jørgen is deteriorating. It’s becoming one of those degenerative conversations where, instead of arguing about the stuff you’re supposed to be arguing about, you start arguing about the language you’re using to argue. A meta-argument. The Five Obstructions is becoming a commentary on itself.

After they watch the fourth film Lars tells Jørgen he’s a tease, and it’s true—Jørgen is a tease. He knows it. He laughs when he hears Lars call him a tease, because now he’s made a freaking cartoon of all things. The two men hang up their phones and Jørgen, who’s in Haiti, says very legalistically and more than a little guiltily that Lars admitted it was a cartoon. Lars sits in his sad, messy little room eating caviar alone with the cartoon image of Jørgen on the television screen behind him.

After Jørgen makes a perfectly fine cartoon, Lars says, I prepared myself for this possibility, and he has. In the event that Jørgen once again bests Lars, which he’s obviously done, even if now he’s cheated a second time, the final obstruction will be that Jørgen reads a text written by Lars.

In this simple act Lars has terminated the conversation; in other words, this is that moment when you totally lose your composure by telling off your friend with such an unholy shitstorm of fury that the entire preceding argument is immediately rendered irrelevant. Lars has pulled out the Big Insult, that one thing you shouldn’t do unless if you’re prepared to end the conversation and face the consequences. And in fact, Lars’s Big Insult is extraordinary. Here we have Jørgen credited as the director of a film that consists of him reading a letter that Lars has written, and which Lars has instructed him in how to read. It gets better: this letter is ostensibly Jørgen indicting Lars for being too pushy, forcing us to assume that Lars is now contrite for how he’s behaved for the whole of the film and wishes to express his remorse through Jørgen’s lips—except that Lars’s contrition is roughly equivalent to the husband of the wife with the black eye. And as an added little cherry of metadiscourse on top, as this letter is read we the viewers will see a montage of scenes from the making of The Five Obstructions, i.e., all the “evidence” of the crime that Lars has just perpetrated and that he is now “apologizing” for through the mouth of the man he has been wronging.

So in other words, in this final film, the summation of this whole thing called The Five Obstructions, Lars and Jørgen are plowing through the crap they’ve created in the process of making the film up to this point. They’ve essentially made a pile of crap for the express purpose of digging into that, instead of the pre-existing pile of crap they were supposed to be digging into to begin with. So has anything at all been accomplished here?

I think so. In this era of unsurpassed crap, we’ve turned to making crap about the crap—that is, we’re now at the point of diving into the pile atop the pile, all that angsty crap that we can’t help but simmer over given the fact of there being so much crap in the world. But the thing is, even if we only ever reach that meta-pile, in a strange way we’re actually digging through the pile underneath at the same time. To phrase it all differently, when you’re trying to fuck with your cinematic mentor’s head today, what you’re really doing at the same time is re-examining that time you fucked the head of that Icelandic actress. And that’s one of The Five Obstructions’s great elegances: it does this in a purely original and non-offensive way that so precious few of our sweating, self-conscious, bastardly unperfect artists ever manage.

As far as the meta-pile goes, Lars has a quite distinguished and long-standing history. In fact, in the breadth and depth of the people’s heads he’s attempted to fuck—and his inventiveness in doing so—he’s almost certainly our most accomplished living filmmaker. Making an entire film about bullying Jørgen is just the beginning. He once sent Björk, who was wrecked by Lars when he directed her in his film Dancer in the Dark, a pillow with the words “If I always allow myself the time to feel my feelings, and then tell what I feel, then Lars can’t manipulate me.” This was after Björk and Lars had conducted a number of pissy little power struggles on the set of Dancer in the Dark. She sent the pillow back and Lars has kept it in his office as a memento of something. Charlotte Gainsbourg, whom von Trier has cut off her own clitoris in Antichrist, said of him, “I really have the impression that I was playing him, that he was the woman, that he was going through that misery, the physical condition, the panic attacks.” He finally got inside of Kirstin Dunst’s head after he filmed a scene of her vagina and referred to it as “the beaver shot.” He’s reputed to have hypnotized a pretty club girl for his second film, Epidemic, made her actually think she was seething with carbuncles, and elicited from her the most perfectly blood-curdling non-acting performance scream of his entire career.

I think from this we can conclude that Lars has a history of failing to get others around him to open themselves to his and their hunger, and when that happens he resorts to tricks designed to dig in to the meta-pile. Ever since his first brushes with film and Danish culture, Lars has shown himself to be a remarkably petty, remarkably headstrong person who will do what the fuck he wants, and you can join him or have him fuck your head. Lars knows nothing of authority; he knows Lars, and he’s always been himself, even when he was a dumb little kid with some hand-me-down reels of film. And Jørgen he regards as a mentor of sorts. There’s a story from Lars’ past, when as a star student at the National Film School of Denmark he tried to get Jørgen’s attention, when of course Jørgen was already a big man of Danish film, and Jørgen completely ignored him. Years later, Lars, by then the terror of Danish cinema, whose avowed purpose was pretty much to shake Denmark’s movie industry out of its pathetic complacency, Lars approached Jørgen and made him his mentor. After all, Lars has never met his true father. On her deathbed in 1989, his mother revealed this secret to him, and in a 2009 interview he called it “a bombshell that is still exploding.”

“You are guiltless. You are like a little child,” Lars says to Jørgen as they head into the studio to make the sixth and final perfect human, starring Jørgen.

Perhaps this is just my own immodestly stupid way of seeing it, but I have a feeling here that Lars finally understands—Jørgen’s perfection is impermeability, and this is all Jørgen is ever going to be to him, so he’s going to end this conversation by turning Jørgen into a perfect little singularity. Plus, this being Lars, he’s going to make Jørgen impermeable in his own little perfectly Lars way: no matter how many times I watch this last remake, I can’t decide who’s saying what. Are these Jørgen’s thoughts, or Lars’, or some combination of the two? My opinion keeps changing as Jørgen reads the letter, and then when I watch it again everything switches up. And then toss on top of that the montage of shots from the preceding 80 minutes of film, plus the fact that I’m actually taking this in via translated subtitles, so I can only really guess at Jørgen’s intonations in various stretches, and you can see, it really is a singularity. This final film becomes a text so deep that it makes the man at its center impermeable.

What Lars likes to do is, he likes to end his films by taking you all the way through to the little singularity that the film has been tunneling toward all along, and then pop you out, alone, on the other side in a sea of black as the credits roll. Thus, for instance, his 2011 film, Melancholia, which concludes with the destruction of the entire Earth. Yes, we see a huge planet run headlong right into our precious Earth, and then Lars goes to the credits. This is pretty much the physical, imagistic omega point of every ending Lars has ever made. For Lars these final few seconds before the credits are the ultimate, the degree zero of the story, and after them there is simply nothing left to tell. Nothing. No sequel, no epilogue. That’s it. Such is the case in The Five Obstructions, whose final few seconds consist of Jørgen reading Lars’s words, “This is how the perfect human falls” as a voice-over to footage of Jørgen pretending to fall down. The words themselves are an ironic quote of Jørgen’s original “Perfect Human,” where these words are said when Claus Nissen falls down—perfectly, of course—which is in itself an irony, because there’s obviously no perfect way to fall down. As Lars both calls himself “perfect” and admits to his “fall,” both ironically, and both through Jørgen’s lips, we see an image of Jørgen falling down, ironically again, filmed way back in Bombay when he was practicing for the role of the perfect human in the second remake. What else can be said? The film has collapsed into itself, it has become an infinitely dense black hole of fallenness, the very embodiment of Lars’s too-offensive search for a truth Jørgen doesn’t want to find, a singularity compressed from the very stuff that had once been The Five Obstructions, and this moment—obviously—assumes pride of place as the very last thing Lars lets us see before the end credits. There is nothing else left to be said. The conversation has concluded in the same way that should every single successful conversation, argument, and session of therapy. This dialectic has spiraled itself right into a point of black that tears just a tiny bit through our idea of reality. It has become art.

—————–

Scott Esposito is the coauthor of The End of Oulipo? (with Lauren Elkin). His writing has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, Drunken Boat, Music & Literature, The White Review, The Point, Bookforum, the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, and many others.