Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps): Animal Collective’s Oddsac, John Zorn’s Astronome, and Candian Hipster Comic Opus Ivory Tower

28.09.10

In the works since 2006, Animal Collective’s “visual album” Oddsac is the headspace-spelunking, lysergic treat that fans have long been clamoring for. While this album-length art film is a slight step backward musically (taking as it does more cues from their 2007 release Strawberry Jam than 2009’s Merriweather Post Pavilion), visually, it’s the natural next step for a band that’s used its music videos to lure audiences into dark corners before assaulting them with monsters, Stan Brakhage-inspired retinal clutter, and disorienting overlays.

In the works since 2006, Animal Collective’s “visual album” Oddsac is the headspace-spelunking, lysergic treat that fans have long been clamoring for. While this album-length art film is a slight step backward musically (taking as it does more cues from their 2007 release Strawberry Jam than 2009’s Merriweather Post Pavilion), visually, it’s the natural next step for a band that’s used its music videos to lure audiences into dark corners before assaulting them with monsters, Stan Brakhage-inspired retinal clutter, and disorienting overlays.

Oddsac’s director Danny Perez had previously worked with the band on their videos for “Peacebone” and “Summertime Clothes” and the creepy creatures he used there are once again put to good use. Early in the film, a young girl tries to contain the bubbling crude that’s pouring from her wall as a mutant version of band member Avey Tare (David Portner) brandishes an autoharp nearby. In the next scene, a hunched figure rinses objects in a pool, gibbering and muttering all the while. And in the DVD’s most dramatic development a vampiric Deakin (Josh Dibb) bleeds bright latex paint when he’s unable to find shelter from the daylight. The connective tissue between monstrous vignettes like these is often abstract—a close-up on a body writhing in sludge or a mesmerizing, fluorescent wormhole—but as with the band’s albums, Oddsac is simultaneously crowd-pleasing and challenging, alienating and comforting. That said, as band member Geologist (Brian Weitz) has warned in interviews, the intended audience isn’t necessarily the band’s entire fan base, and those who’ve come to them through the relatively accessible Merriweather might want to do a gut check before diving in.

For one thing, there aren’t any catchy earworms that burrow as aggressively as “My Girls” or “Grass” here since much of the DVD is comprised of glittering electronic washes of noise and lazy acoustic-guitar driven journeys through the back country in search of psilocybin mushrooms. “Screens” is an especially fruitful jaunt, splicing Brian Wilson melancholia with Animal Collective circa Sung Tongs to soundtrack Deakin’s journey by canoe. It’s a testament to the wealth of bizarre imagery found here that an undead creature paddling through tar-black water can provide such a pacific moment.

Oddsac may be otherworldly, but it’s not necessarily unfamiliar. The first shot is of a field at night, with a crisp line drawn between illuminated grass and the ominous void beyond. It’s more than a little reminiscent of Michael Vahrenwald’s photography series “Universal Default,” and it demonstrates the disturbingly thin border between the everyday and the tragic that defines much of the film. Later, after administering some smelling salts following about ten minutes of sustained ambient noise and delicately plucked guitar, Panda Bear (Noah Lennox), decked out in a long white wig, surveys a field of stones from his drum kit in the center before pounding away with abandon. If you recognize the footage, that probably means you’ve attended one of his solo shows, in which the rock field scene is often projected during performances of the song “Carrots.” Now it’s the visual accompaniment to a repetitive (not to say boring) track with vocals that scale a vertiginous sequence of notes, always with a comforting cushion of synthetic squish underneath to break any falls.

Being stoned out of your mind can get interminable when all you really want is to get back to reality, and Oddsac can’t avoid the hangover forever. The ending aims for a jubilant bit of creation/destruction like the final scene of Richard Linklater’s Slacker in which the endless verbal speculation and analysis stops and the kids on screen whip out their own camera, only to toss it over the side of a mountain. But on Oddsac the gesture falls a bit flat, maybe because it’s too reminiscent of the Matt & Kim video for “YEA YEAH,” or maybe because the monster’s heart just isn’t in it. Whatever the weaknesses of the ending, Animal Collective’s visual offering barely overstays its welcome at 51 minutes. And as far as endurance tests go, even at its most abstract, it has nothing on the hyper-difficult opera Astronome.

Being stoned out of your mind can get interminable when all you really want is to get back to reality, and Oddsac can’t avoid the hangover forever. The ending aims for a jubilant bit of creation/destruction like the final scene of Richard Linklater’s Slacker in which the endless verbal speculation and analysis stops and the kids on screen whip out their own camera, only to toss it over the side of a mountain. But on Oddsac the gesture falls a bit flat, maybe because it’s too reminiscent of the Matt & Kim video for “YEA YEAH,” or maybe because the monster’s heart just isn’t in it. Whatever the weaknesses of the ending, Animal Collective’s visual offering barely overstays its welcome at 51 minutes. And as far as endurance tests go, even at its most abstract, it has nothing on the hyper-difficult opera Astronome.

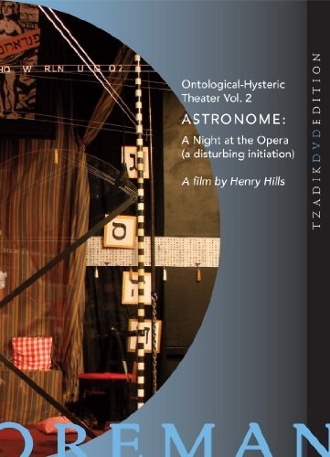

Sultan of saxophone skronk John Zorn and doggedly anti-narrative playwright Richard Foreman have more in common than just their MacArthur “genius” Fellowships and a yen for the avant-garde—they also love to play in the muck. For Zorn that means swapping genres midstream like Looney Tunes composer Carl Stalling, engaging in noise-for-the-sake-of-noise, and turning Ornette Coleman numbers into addle-brained anti-jingles. For Foreman it’s directing his actors to pantomime the basest human acts and covering the floor of his Ontological-Hysteric Theater with all manner of garbage: tarot cards, shredded gypsy costumes and makeshift eruvs (the suspended strings that allow observant Jews to carry objects on the Sabbath). No one would deny that the two aspire to high art, but they often enter through the service entrance, eschewing language and traditional structure in favor of noisy, sweaty spectacle that’s practically impervious to interpretation or empathy. So when Foreman used Zorn’s pocket opera Astronome as a jumping-off point, it felt like a natural fit. Enter Astronome: A Night at the Opera (A Disturbing Initiation), the bulkily titled result, with experimental filmmaker Henry Hills responsible for melting six live performances down into this DVD release from Zorn’s record label Tzadik.

‘Tzadik’ is the Hebrew word for “righteous one,” but the closest thing to righteousness in the world of Astronome is the corpse of a false messiah hanging from the rafters. As in Foreman’s Wake up Mr. Sleepy! Your Unconscious Mind is Dead! and most of his oeuvre, Astronome is a Brechtian assault that makes no attempt to pass for reality or build a story. Instead it’s a bizarre succession of human figures interacting with semi-recognizable objects—like a slug marionette, or the broken pair of pince nez from the Odessa steps sequence of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Between tableaux, the cast all but disappears, revealing a litter-strewn stage that looks like it’s ready for the night janitor. At other times the characters clean walls, masturbate with pepper mills, or get into knife fights. Like Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou, Astronome isn’t a collection of symbols waiting to be decoded; it’s a tasting menu of (hopefully) moving images, meant to be experienced on a pre-verbal level.

The characters who populate the stage describe quite a flavor palette: a man in greenface chokes himself with his own necklace, an enormous schnoz and an enormous mouth sits impassively before chowing down on an actor, and the rest of the cast—kitted out in veils, fezzes and aprons—sometimes reacts to Zorn’s score and sometimes remains oblivious, which is no easy task as the music’s pretty hard to ignore. Astronome is one of the albums that Zorn composed and then delegated to other musicians. Here, Mr. Bungle’s Mike Patton and Trevor Dunn layer guttural, stuck-pig vocals and thudding Stone-Age basslines over Joey Baron’s drumming, producing a collective wallop that feels like tectonic plates slipping over each other. Sludgy, THC-laced metal gives way to moments of acoustic violence capable of separating Pangaea, and a jazz groove slowly evolves from the primordial mud. The musical planet being created is now able to sustain life, and Patton breaks the near-silence with a few bird calls, and some booming pronouncements that sound like God hovering over the surface of the waters.

The characters who populate the stage describe quite a flavor palette: a man in greenface chokes himself with his own necklace, an enormous schnoz and an enormous mouth sits impassively before chowing down on an actor, and the rest of the cast—kitted out in veils, fezzes and aprons—sometimes reacts to Zorn’s score and sometimes remains oblivious, which is no easy task as the music’s pretty hard to ignore. Astronome is one of the albums that Zorn composed and then delegated to other musicians. Here, Mr. Bungle’s Mike Patton and Trevor Dunn layer guttural, stuck-pig vocals and thudding Stone-Age basslines over Joey Baron’s drumming, producing a collective wallop that feels like tectonic plates slipping over each other. Sludgy, THC-laced metal gives way to moments of acoustic violence capable of separating Pangaea, and a jazz groove slowly evolves from the primordial mud. The musical planet being created is now able to sustain life, and Patton breaks the near-silence with a few bird calls, and some booming pronouncements that sound like God hovering over the surface of the waters.

These serve as a sort of echo to the voiceover (courtesy of Foreman) that divides Astronome‘s scenes. It’s a room-filling yawn that might be God again, but this time half-asleep on the seventh day of creation. This voice delivers pearls of wisdom like “There exists inside me an avenging angel named ‘not,'” and “Remember: it’s very easy to follow the negative path to avoid things that are painful,” in between repeated intonations of the words ‘stage fright.’ Besides reminding the viewer that they’re watching a performance, not reality, the repetition of these two words create a mantra-like rhythm and underscore how Foreman’s plays often adhere to musical structures in the way they revisit themes and follow movements without necessarily providing meaning or motivation.

As with the score, the actors seem only dimly aware of the voice. Even more than Foreman’s Bridge Project plays, which layered video projections onto the live performances as a type of visual soundtrack, Astronome is divided along media lines. The visual tableaux and Zorn’s music would be punishing enough taken on their own, but together they’re wearying, feeling as they do like separate works scrapping for the viewer’s attention. It doesn’t help matters that director Henry Hills’ video is a grainy, visually noisy affair that suffers from insufficient light, and that no attempt was made to overdub the dialogue with the theater’s acoustics in mind. Hills also supplies the DVD’s one featurette: a selection from his own film Emma’s Dilemma cut together with an interview of an unusually humble Foreman. Charming as it is, the interview skimps on the content in favor of interminable footage that winds and rewinds, speeds and slows, as if an editor was dragging the playhead back and forth in Final Cut Pro. For fans of Foreman’s earlier, purely theatrical work, Astronome is a fitfully engaging return to form after a somewhat disturbing flirtation with the movie screen. Zorn fans, however, are probably better off enjoying the album by itself. If nothing else, it’s an opera that demonstrates how any sound can become music and any movement can become dance, simply through repetition.

At the complete opposite end of the taking-itself-seriously spectrum lies Ivory Tower, which is being billed as an “existential sports comedy,” about chess, but more often just feels like an opportunity for Canadian music scenesters like Peaches, Tiga, Feist, and Chilly Gonzalez to moonlight as professional cut-ups—which is not necessarily a bad thing. Directed by first-time filmmaker Adam Traynor of German hip hop/puppet ensemble Puppetmastaz (whose ranks include Gonzalez), and co-written by director Celine Sciamma (Water Lillies), the film revolves around a pair of brothers, Herschel (Gonzalez) and Thaddeus Graves (Juno Award-winning DJ and producer Tiga) whose lives have taken them in very different directions, despite the fact that they share the same guiding star: chess. Schlubby fading prodigy Hersch returns home to his bedridden mother and ex-girlfriend Marsha Thirteen—played by Peaches, who probably frequents the same stylist as Jerry Blank, the unkempt ex-prostitute from Strangers with Candy. During his time away, Hersch has become obsessed with a worthless concept called “Jazz Chess.” It’s “the art and science of chess as Buddha would play it” with no winners, no losers, and no conceivable point. While Hersch was wandering in the philosophical wilderness, his pragmatic brother Thad stepped in, took the Canadian chess world by storm, swept Marsha off her feet, and adopted skinny blue suits and self-aggrandizing wordplay like “The H is silent, the crowds—another story.”

At the complete opposite end of the taking-itself-seriously spectrum lies Ivory Tower, which is being billed as an “existential sports comedy,” about chess, but more often just feels like an opportunity for Canadian music scenesters like Peaches, Tiga, Feist, and Chilly Gonzalez to moonlight as professional cut-ups—which is not necessarily a bad thing. Directed by first-time filmmaker Adam Traynor of German hip hop/puppet ensemble Puppetmastaz (whose ranks include Gonzalez), and co-written by director Celine Sciamma (Water Lillies), the film revolves around a pair of brothers, Herschel (Gonzalez) and Thaddeus Graves (Juno Award-winning DJ and producer Tiga) whose lives have taken them in very different directions, despite the fact that they share the same guiding star: chess. Schlubby fading prodigy Hersch returns home to his bedridden mother and ex-girlfriend Marsha Thirteen—played by Peaches, who probably frequents the same stylist as Jerry Blank, the unkempt ex-prostitute from Strangers with Candy. During his time away, Hersch has become obsessed with a worthless concept called “Jazz Chess.” It’s “the art and science of chess as Buddha would play it” with no winners, no losers, and no conceivable point. While Hersch was wandering in the philosophical wilderness, his pragmatic brother Thad stepped in, took the Canadian chess world by storm, swept Marsha off her feet, and adopted skinny blue suits and self-aggrandizing wordplay like “The H is silent, the crowds—another story.”

Marsha is the trophy both Graves boys are ultimately after, but the film lives or dies by the success of its wordy, winningly daft, idiosyncratic sense of humor, rather than the punchiness of its training montages or the dramatic arcs of its characters. It’s a flat, indifferently shot film that in its worst moments brings to mind a comedy sketch stretched long past the breaking point. And even at a slim 75 minutes, it can feel a little draggy once the one-note characters have demonstrated all their tricks. A free-jazz experiment conducted with pawns, queens, and rooks goes on forever, awkward blocking mars a few scenes, and back-to-back dueling commercials (larded with canned motion graphics and inept green screen effects) earn laughs, but in the process transfer some of their low-budget grime to the rest of the film.

At its best, though, Tower gives off the infectious energy of a project seemingly taken up on a whim by a group of friends with talent to burn. Tiga’s deadpan, monomaniacal performance is especially good. When he produces unfortunate rhymes like “It was not always so rad… being Thad… around Dad,” it’s not clear whether he stumbled or leapt into them, and he wears the chip on his shoulder like it was surgically implanted there. Gonzalez pulls double duty as the film’s protagonist and its music composer, overlaying scenes with piano-driven Europop pastiches that have little in common with the Erik Satie-inflected minimalism of his most heralded album, Solo Piano. And even though Feist’s supporting turn isn’t much bigger than a cameo, she makes the most of it, displaying some of the comic chops that she used to warm up Peaches’ fans years ago when they roomed together. It’s a film that doesn’t pretend to offer much more than a few good jokes. Fortunately, aside from a late-film longueur, it mostly delivers on that promise—even if those gags are generally of the wry grin instead of gut-busting variety. And if Ivory Tower pulls some faces at the kind of self-importance found in Astronome and Oddsac—while tossing a few catchy tunes into the mix—all the better.

____________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Forget the Hits: Here is Animal Collective

Daniel Nester Reviews His Friend Eric’s Hard Drive

The Sound of an Electronic Summer: Matmos, Tobacco, The Books and Autechre