The 2010 New York Film Festival

24.09.10

By far the most frequently asked question your Fanzine correspondent has been getting about the 48th New York Film Festival—which opens tonight at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall—is whether “that Facebook movie” is any good. And the answer is, I don’t know. As usual, many of the most hotly anticipated films in the NYFF lineup won’t be screened in advance for us journos until after we go to press, and that includes David Fincher’s The Social Network, the festival’s much-hyped opening night selection about the origins of the website everyone loves to love-hate.

By far the most frequently asked question your Fanzine correspondent has been getting about the 48th New York Film Festival—which opens tonight at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall—is whether “that Facebook movie” is any good. And the answer is, I don’t know. As usual, many of the most hotly anticipated films in the NYFF lineup won’t be screened in advance for us journos until after we go to press, and that includes David Fincher’s The Social Network, the festival’s much-hyped opening night selection about the origins of the website everyone loves to love-hate.

Sight unseen, though, The Social Network is representative of a general trend in this year’s programming. The estimable NYFF selection committee (comprised of critics Melissa Anderson, Scott Foundas, Dennis Lim, and Todd McCarthy, along with Film Society of Lincoln Center Program Director Richard Pena) appears to have gone whole hog this September for movies that are not only heady and intellectual—which is to be expected—but also relevant. Movies, that is, that attempt to explain where we are now and how the hell we got here. Is that what we want?

Earlier this week, The National Bureau of Economic Research declared that our current recession was not only over, but had actually been over since June of 2009. This won’t mean squat, of course, to the millions of Americans who remain unemployed, nor to those who have low-paying jobs and still can’t make ends meet. Traditionally, during hard times, these folks have gone to the movies in large numbers, in part to escape their troubles. It’s no accident that Hollywood’s first Golden Age coincided with the Great Depression. But with Netflix and quality cable TV offering cheaper and increasingly better options than what you’ll find at the multiplex, domestic box office receipts are down, way down. Meanwhile, a clueless American film industry seems to think the solution is to slap crappy 3-D effects onto their films, post-production, and then to raise their ticket prices. All of which is to say, that this year’s festival—though it includes middlebrow Oscar fodder like The Social Network, Clint Eastwood’s Hereafter, and Julie Taymore’s The Tempest—has stayed true to its highbrow roots, and is no one’s idea of populism.

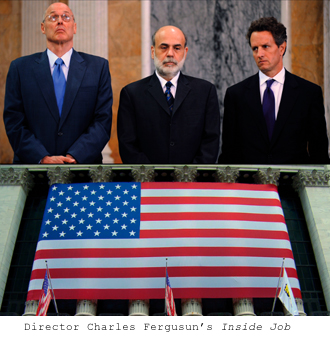

Now, I can’t wait to see Jesse Eisenberg (a talented young actor whom I like to think of as the anti-Michael Cera) play the world’s youngest billionaire, Mark Zuckerberg, as a consummate asshole. But is Charles Ferguson’s muckracking new documentary about financial deregulation, Inside Job (which, admittedly, I haven’t seen yet), really what recession audiences are looking for? Frankly, I thought Ferguson’s previous effort—No End in Sight—was bloodless. Or, if you prefer, I found it a little too fair and balanced, assigning blame for the Iraq War on mere poor judgment, rather than a toxic combination of poor judgment, greed, corruption, and mendacity. In any case, Robinson in Ruins—a pretentious and incoherent look at our economic meltdown from a UK perspective, which I have seen—is definitely not the kind of NYFF movie that’s going to bring the masses back to theaters.

Now, I can’t wait to see Jesse Eisenberg (a talented young actor whom I like to think of as the anti-Michael Cera) play the world’s youngest billionaire, Mark Zuckerberg, as a consummate asshole. But is Charles Ferguson’s muckracking new documentary about financial deregulation, Inside Job (which, admittedly, I haven’t seen yet), really what recession audiences are looking for? Frankly, I thought Ferguson’s previous effort—No End in Sight—was bloodless. Or, if you prefer, I found it a little too fair and balanced, assigning blame for the Iraq War on mere poor judgment, rather than a toxic combination of poor judgment, greed, corruption, and mendacity. In any case, Robinson in Ruins—a pretentious and incoherent look at our economic meltdown from a UK perspective, which I have seen—is definitely not the kind of NYFF movie that’s going to bring the masses back to theaters.

And still, I have to confess that some of the most rewarding pictures on this year’s NYFF schedule—the films I have been most impressed with—can hardly be called escapist fare for the common man. Indeed, two of them in particular are as preoccupied with recent international events as any of the films I’ve already mentioned, and their point exactly is to reconcile yesterday’s papers with today’s headlines.

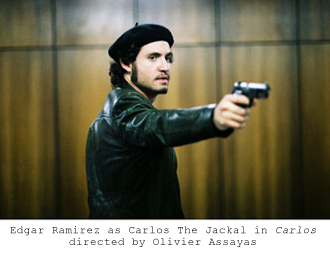

The first of these films is Carlos, Olivier Assayas’s three-part, 319-minute biopic of Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, the Venezuelan born terrorist-for-hire who, under the nom de guerre The Jackal, caused havoc around the globe for more than three decades until French authorities finally captured him in the mid-1990s. Carlos, which stars Edgar Ramirez (Domino) in a career-making performance, will air on the Sundance Channel (one of the movie’s financial backers) in October, and thereafter be released in theaters in both its full-length triptych version and in a more accessible two-and-a-half hour cut. Shot on location in Europe and the Middle East, Carlos posits the gradual transformation of its protagonist from lean Marxist idealist to fat capitalist mercenary as an allegory for our times, a way of understanding how our geopolitics transitioned so seamlessly from the Cold War epoch to the age of terror.

Equally topical, but requiring even greater patience from its audience, is a three-hour unnarrated documentary sarcastically entitled The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu. Assembled by one-time Romanian exile Andrei Ujica entirely from the state footage Ceausescu himself commissioned during his years as the Eastern Bloc’s most ruthless strongman, the film is a vision of how the former communist leader must have seen himself. With the exception of the opening and closing scenes, both of which take place after his ouster, the atrocities for which Ceausescu was responsible are pointedly missing from the screen, and barely hinted at. Instead, you the viewer must pay careful attention to the little details pointing, here and there, to the truth—as, for example, when Ceausescu is shown brazenly cheating during a casual game of volleyball. It’s one thing to see this tyrant hobnobbing with a young Kim Jong-il, an aging Chairman Mao, or even a visiting Richard Nixon. But it’s another thing altogether to watch him schmooze Jimmy Carter in the Rose Garden in broad daylight. Like Carlos, Ujica’s wry epic implies that history’s brutes are not abstractions, nor are they outlaws with whom we refuse to negotiate. On the contrary, they walk freely among us.

Equally topical, but requiring even greater patience from its audience, is a three-hour unnarrated documentary sarcastically entitled The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu. Assembled by one-time Romanian exile Andrei Ujica entirely from the state footage Ceausescu himself commissioned during his years as the Eastern Bloc’s most ruthless strongman, the film is a vision of how the former communist leader must have seen himself. With the exception of the opening and closing scenes, both of which take place after his ouster, the atrocities for which Ceausescu was responsible are pointedly missing from the screen, and barely hinted at. Instead, you the viewer must pay careful attention to the little details pointing, here and there, to the truth—as, for example, when Ceausescu is shown brazenly cheating during a casual game of volleyball. It’s one thing to see this tyrant hobnobbing with a young Kim Jong-il, an aging Chairman Mao, or even a visiting Richard Nixon. But it’s another thing altogether to watch him schmooze Jimmy Carter in the Rose Garden in broad daylight. Like Carlos, Ujica’s wry epic implies that history’s brutes are not abstractions, nor are they outlaws with whom we refuse to negotiate. On the contrary, they walk freely among us.

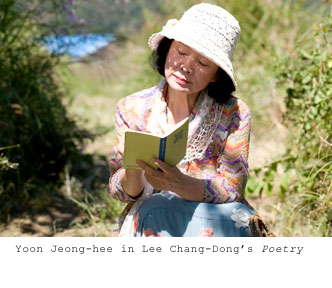

If I’m making this year’s NYFF highlights sound grim, pedantic, and overly political, I certainly don’t mean to. Two of the other standout selections this year, for instance, are films that take on death as their subject, and yet do so with unexpected levity. In Lee Chang-Dong’s Poetry, legendary Korean actress Yoon Jeong-hee plays a sixty-ish woman grappling with the onset of Alzheimer’s while raising a no-good teenage grandson involved in a horrific crime. Bringing together disparate, dark plot elements into an improbably successful and beautiful whole, Poetry shouldn’t feel so life affirming, but it does. Similarly, Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest, Uncle Boomee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, is a movie about dying—in this case, of kidney failure. The winner of this year’s Palme D’Or at Cannes, Uncle Boonmee is a mystical head trip that scans like a Buddhist 2001: A Space Odyssey, as a fellow critic had pointed out, and reminded me of how hypnotic and otherworldly movies can be even, or especially, without the aid of computer generated imagery.

Also worth checking out is Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy, which begins as an arthouse-meet-cute-romcom in which a would-be couple (Juliette Binoche and British opera star William Shimell) go on a date in more-or-less real time, but which slowly morphs into a surrealist, what-the-fuck meditation on originality and identity. I can also recommend—to diehard Beatles fans, at least—LennonNYC, a documentary by Michael Epstein about the Walrus’s final years in Manhattan, when he fought the federal government for his green card. Although the subject has already been covered exhaustively in films like Imagine and The U.S. vs. John Lennon, LennonNYC offers a bounty of unreleased home footage, fly-on-the wall audio recordings from the Double Fantasy sessions, and an amazing radio interview I’d never heard before in which the singer promotes his Walls and Bridges album and talks about his love for the Big Apple. Many New Yorkers, myself included, can recognize themselves when Lennon says, “I’ve met a lot of people in New York who complain about it, but none of them leave.”

Also worth checking out is Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy, which begins as an arthouse-meet-cute-romcom in which a would-be couple (Juliette Binoche and British opera star William Shimell) go on a date in more-or-less real time, but which slowly morphs into a surrealist, what-the-fuck meditation on originality and identity. I can also recommend—to diehard Beatles fans, at least—LennonNYC, a documentary by Michael Epstein about the Walrus’s final years in Manhattan, when he fought the federal government for his green card. Although the subject has already been covered exhaustively in films like Imagine and The U.S. vs. John Lennon, LennonNYC offers a bounty of unreleased home footage, fly-on-the wall audio recordings from the Double Fantasy sessions, and an amazing radio interview I’d never heard before in which the singer promotes his Walls and Bridges album and talks about his love for the Big Apple. Many New Yorkers, myself included, can recognize themselves when Lennon says, “I’ve met a lot of people in New York who complain about it, but none of them leave.”

I did some complaining myself earlier, but the fact is that this year’s NYFF schedule is as solid as ever. There are several features I still haven’t seen but am very much looking forward to, including Cristi Puiu’s Aurora, Pablo Lorrain’s Post Mortem, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme (a title which sounds pretty enticing to me, but which I realize probably sounds like a warning to most everyone else). Hollywood has reached a nadir from which it might never recover, but Lincoln Center’s programming is proof that filmmakers around the world still know how to make motion pictures we can actually get excited about, the kind of movies that will make us smile days after we’ve seen them and thereby help us get through the worst of times.