Real Escapism: Kentucker Audley and Team Picture

03.11.08

You can’t really talk about Team Picture without mentioning Mumblecore at this point, which is unfortunate, considering how many things the film does as you watch it, and what an accomplished stylist the director clearly is. Mumblecore might have died a slow death as a conversational segue into a group of films and filmmakers Kentucker Audley has fallen in with, the most active verb of which has been Cassavettes, but Audley’s Team Picture has a much wider array of precedents, and Audley especially seems too full of ideas and idiosyncratic talent to pitch his tent for very long in anyone’s camp.

You can’t really talk about Team Picture without mentioning Mumblecore at this point, which is unfortunate, considering how many things the film does as you watch it, and what an accomplished stylist the director clearly is. Mumblecore might have died a slow death as a conversational segue into a group of films and filmmakers Kentucker Audley has fallen in with, the most active verb of which has been Cassavettes, but Audley’s Team Picture has a much wider array of precedents, and Audley especially seems too full of ideas and idiosyncratic talent to pitch his tent for very long in anyone’s camp.

What people tend to say when they leave a mumblecore film, whether they get on board and sit through it or get fed up and leave early, is that nothing happens. And yet the directors of these films will tell you that they would rather present things as they happen than conspire to arrange dramatic incident and emotional theatrics. Certainly Audley talks about wanting to avoid rigging things in his films. “I don’t want to make art films where you’re waiting for a character to accomplish a specific thing.” That’s an interesting ambition within a culture where every word must mean something and every action must lead somewhere, but to say making this kind of film is closer to real life is probably more than a little disingenuous. Real life is full of incident, and people build narratives for themselves in order to understand who they are and what they’re doing, and why. In real life, people talk more often than not, and bring to their conversations ever-shifting agendas and desires. In real life, you’re performing from the moment you’re aware of yourself, gauging reactions, reacting accordingly, modifying your demeanor and expression to steer interaction or events in ways which make you feel alive. In real life, narratives collide indiscriminately. It’s true that not a lot is going on in Team Picture, not in terms of plot, at least in the way plot is generally constructed in films. That has more to do with film than with reality, and it might not be your thing. In fact, this kind of movie seems more like a reaction against the ceaseless, posturing emptiness of reality and its messy collisions of narrative than an investigation into the fantasy of what reality is alleged to feel like.

There’s also the fact that to make a movie, even one made as cheaply as Team Picture reportedly was, one organizes and structures and controls. The impression one has watching a movie of Team Picture‘s pace and pitch is that the camera was simply set up and allowed to run. Often, the directors of these films contribute to this mistaken impression of cinema verite, not just by saying they aim to represent the real world and real people but because, like Audley, they often assert that they’re merely playing themselves when they move from behind the camera and step in front of it. Being oneself in front of a camera is a contradiction of terms. It isn’t easy to do, if it happens to be possible, and anyone who attempts to do it is immediately faced with the question of who he is exactly and what it is to be that. You’re going to need a boom for this kind of film, if you want things to sound realistic, rather than merely videotaping the drama, and someone will have to listen for traffic. If a car passes and you can’t work the car into the scene in a way which feels authentic to the narrative at hand, you’ll need to back up and repeat the line. Try being yourself, whatever that is, after saying the same bit of dialogue ten times, let alone four. Try to imagine what a person like you would do in a situation like this without dispensing at least partially with fixed ideas about identity. To come across as oneself on film, as people tend to construe that, typically belies an out-of-body experience and involves a great deal of make-believe.

Team Picture presents Andrew Nenninger as the character Kentucker Audley, a name which also happens to be a pseudonym for its director. Kentucker is acting with people who are not his parents but pretend to be. In directing his movie, which is meant to reflect real life, he will need to make arrangements with various locations to use their property: a restaurant will have to agree to quiet everything down for a time, which might mean closing or allowing access after hours. A restaurant which isn’t open but pretends to be isn’t a real restaurant in the way most people conceive of one. People pretending to eat in such a restaurant automatically become characters. If Kentucker can’t use his own house he will have to borrow someone’s. Three separate locations might have to be used to represent a single dwelling on film. Java Cabana will have to agree to allow yet another filmmaker to use its premises as a generic-looking artsy coffee house. His real girlfriend might play the girlfriend he breaks up with. She might sit by while he hooks up with another girl, telling herself what he tells her: it’s only a movie.

Team Picture presents Andrew Nenninger as the character Kentucker Audley, a name which also happens to be a pseudonym for its director. Kentucker is acting with people who are not his parents but pretend to be. In directing his movie, which is meant to reflect real life, he will need to make arrangements with various locations to use their property: a restaurant will have to agree to quiet everything down for a time, which might mean closing or allowing access after hours. A restaurant which isn’t open but pretends to be isn’t a real restaurant in the way most people conceive of one. People pretending to eat in such a restaurant automatically become characters. If Kentucker can’t use his own house he will have to borrow someone’s. Three separate locations might have to be used to represent a single dwelling on film. Java Cabana will have to agree to allow yet another filmmaker to use its premises as a generic-looking artsy coffee house. His real girlfriend might play the girlfriend he breaks up with. She might sit by while he hooks up with another girl, telling herself what he tells her: it’s only a movie.

In Team Picture, Kentucker goes to Chicago with the other girl he hooks up with, who in the story lives or is staying next door. Are we to presume that he met this girl while the camera was going, and we happen to watch the blossoming of their real time relationship? Driving on the road, he looks at her sleeping in the passenger seat, studying her figure. We see it from his point of view, which means that the cameraman sat where the driver would and filmed the shot, and Kentucker himself, if not holding the camera, was either in the backseat or, possibly, not even in the car at all. The Director of Photography, also acting, i.e. being himself, in the movie, sometimes has someone else hold the camera. The way a film elides all these things and allows you to watch its story without the interruption of the shoot’s circumstances is through control and deceit. The way it creates a convincing, consistent impression of everyday banality is by concealing the real life dramas and interruptions happening off camera, several feet away, or right in front of it, hidden in the director’s head, so to talk about truth in filmmaking, let alone reality, is from the outset a very tricky proposition, itself at risk of dishonesty.

The disparity between what feels real on film and what feels real in real life is so huge as to be negligible. Film is nothing at all like real life in the ways you expect. You don’t point and shoot. You plot, rehearse, wait, and wait some more. To be worried about a shot and to trouble over a scene takes the filmmaker immediately out of real life, unless your real life means you’re making a movie. If your aspiration as a director is to get at something real in a movie, you hardly need to dispense with story, and in fact Audley doesn’t. Team Picture might be blissfully devoid of melodramatic incident, the kind of empty noise celebrated by the film-going public at large, but it tells a story and works within the established rules of narrative, cinematic and otherwise. Its true masterstroke is coming at story in a different way, making its audience conscious of narrative and the neediness we have for it. What happens when you withhold it? How far can you remove its elements before it ceases to be? The brilliance of Team Picture and Audley’s approach (and, be sure, there is one) is that it asks you to be conscious of narrative and motivation in ways reality infrequently calls upon you to do.

The disparity between what feels real on film and what feels real in real life is so huge as to be negligible. Film is nothing at all like real life in the ways you expect. You don’t point and shoot. You plot, rehearse, wait, and wait some more. To be worried about a shot and to trouble over a scene takes the filmmaker immediately out of real life, unless your real life means you’re making a movie. If your aspiration as a director is to get at something real in a movie, you hardly need to dispense with story, and in fact Audley doesn’t. Team Picture might be blissfully devoid of melodramatic incident, the kind of empty noise celebrated by the film-going public at large, but it tells a story and works within the established rules of narrative, cinematic and otherwise. Its true masterstroke is coming at story in a different way, making its audience conscious of narrative and the neediness we have for it. What happens when you withhold it? How far can you remove its elements before it ceases to be? The brilliance of Team Picture and Audley’s approach (and, be sure, there is one) is that it asks you to be conscious of narrative and motivation in ways reality infrequently calls upon you to do.

Team Picture is a gorgeous movie, sad and dreamy in places, with a quality of acting and characterization and an ear for sound and nuance that few movies achieve. I got so excited watching this movie where nothing is said to be happening that I could barely contain my imagination and sit still. I’d watched a music video beforehand. I don’t dance, which is to say I don’t think of myself as someone who does, or don’t wish other people to perceive me that way, but the dancing in the video had a similar effect to watching Team Picture. It made me think about myself differently. It made me want to express a different side of myself, to slow things down or speed them up, to play with time and limits of silence and sound, to burrow in or out of who I think of myself as, to get closer to something about myself or other people. That’s what really good film and insightful performance does to me. It’s an escape of some kind that elicits some well of real feeling. The most patently melodramatic film can put you in touch with reality; scenes of pure fantasy can make you feel more intensely than you normally do, to make you aware of feeling, what it means to feel. People have been seeing themselves in actors for years, and understanding themselves better. The performer in you watches a good actor and learns.

Audley’s delivery recalls the stylized performances of old screwball comedy in certain ways. Comic timing is all about withholding, and Audley takes withholding to extremes, making conversation out of indirection, using only the words most people throw out in an effort to make themselves understood. His performance in Team Picture is so incredibly precise in its indirection that you don’t think of it as a performance at all, adding to the confusion between real and unreal. He isn’t interested in playing other people, he recently said, but read any interview with him online and you’ll see, by contrast, how accomplished his acting here truly is, and what a highly specialized expression of his personality it is, meaning that it conveys several aspects of who he might be to heightened effect. When called upon to explain himself or articulate his ideas, Audley does so with admirable intelligence and a specificity which would leave his character in Team Picture staring blankly back at him. Actors are always playing other people. Conversely, even when they’re playing Shakespeare, they’re playing themselves, drawing on who they are and how they feel and their wealth of experience. Cassavettes played plenty of other people on screen, getting closer and closer to who he was off camera.

Team Picture reminds of Beckett, Antonioni, and even Woody Allen more than Cassavettes, for that matter. It plays with silence and space, action and inaction, in ways Antonioni explored, moves ahead through sidelong steps and speaks in a coded, highly stylized language, like Beckett. Your mind works within those spaces in some fairly interesting patterns. Audley’s performance has the neurotic indecisiveness of Woody Allen on barbiturates. It’s amazing to watch, and makes me excited to see what he’s capable of, as Kentucker Audley or someone else; as anyone at all. His facial expressions recall the silent cinema of Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. His awareness of gesture, conscious or intuitive, is similar to theirs. None of these comparisons could possibly please someone intent on playing himself. Audley might prefer not think of himself as a dancer either.

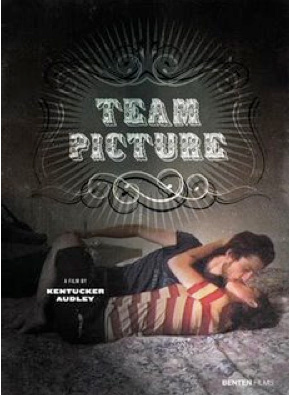

opening photo: Andrew Nenninger as Kentucker Audley playing Kentucker Audley, meeting the girl next door

Read more of Pera’s writing on film at his blog Intermittent Movement.