The Air We Breathe: Artists and Poets Reflect on Marriage Equality

08.12.11

The Air We Breathe:

Artists and Poets Reflect on Marriage Equality

Ed. Apsara DiQuinzio

SFMOMA

$19.95

144 p.

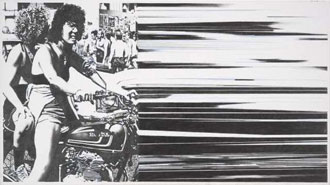

At first glance The Air We Breathe seems to be the typical plush printed volume that accompanies any major exhibition––in this case the show of the same name at SFMOMA. Conceived and edited by Apsara DiQuinzio, the project’s book form actually predated the show. The result is unconventional marriage itself––a combination of an “art book” (complete with lovely full page prints and critical/contextual essays) and an illustrated poetry anthology. Subtitled Artists and Poets Reflect on Marriage Equality, the wide variety of those reflections begin with a clever cover design taken from DL Alvarez’s piece You Need A Civil Rights Bill, Not Me. On the front are lines upon lines, some wide and wavelike, some small and lightly colored. The title is embossed upon these in graceful, generic, silver letters that invoke weddings, anniversaries, and other formal occasions. The effect is a generalized dignity––musical and abstract. Imagine Sol Lewitt working for Hallmark Cards. On the back however are two women straddling a motorcycle in the midst of a 70’s Gay Pride Celebration. Joyous and gritty, they bring “Born To Run” immediately to mind. Front and back images seem to be of very different worlds, until opening the book fully the entire image can be seen. Now the edge of the bike bleeds into the graphic lines, transforming them into seismic skid marks, sound waves––the musical score for these gals’ big machine and the Springsteen song the are definitely going to fuck to when they get home. The hellion energy of Alvarez’s piece may be tamed by the flat elegance of the book’s title, but the combination makes a fitting summation of the multiple, often contrary positions found on the pages within.

In her opening essay “My Gay Marriage,” Eileen Myles points out the “wobbly singularities” and personal journeys that queer/LGBT individuals face before becoming married to their larger community. Riffing playfully and insightfully on the “gay” and “straight” qualities of each piece and contributor, Myles sets the stage for the passage back and forth between the erotic, the poignant, and the outraged that make The Air We Breathe so satisfying. Will Alexander’s “On Osmotic Attraction” pits the enormity of desire against state control, asking, “How can the extrinsic regulate the feral?” This tension is further exemplified in the poems I Do by Ariana Reines, “Shards” by George Albon, and Elliot Hundley’s dynamic collage (also titled The Air We Breathe).

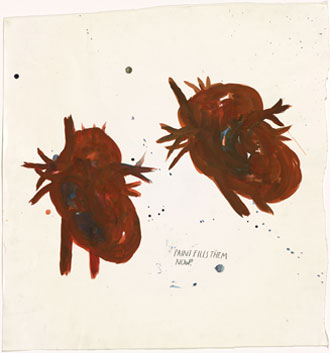

On a more domestic but no less socially challenging note, Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian speculate on the shifty language of partnership in their dialectic lyric “Behold the Bride/Groom.” Taking on historical representations of unsanctioned union and desire, Colter Jacobsen’s The Boy’s Book of Magnetism evokes obscure 19th century yearnings and half-memories with illustrative, shadowy graphite, while works by Matt Keegan, Carlos Motta, and Sharon Hayes recall the hard-edged graphic images and brassy identity polemics of the 90’s culture wars. Robert Gober contributes a scrawled off post-it note that begins with “first they came for the gays…” and ends with “so who gives a shit?” Gober’s ironic acid is matched by the sincere tenderness found in Nicolas Paris’s delicately formal Amantes (lovers), Raymond Pettibon’s loose and gentle painting of two hearts No Title (Paint fills them) and sensual portraits of female couples by Nicole Eisenman and Laylah Ali. In a decisive move to reaffirm the project’s agenda, the book concludes with Frank Rich’s editorial writings on gay marriage, Martha C. Nussbaum’s essay on the history and philosophy of marriage, and Untitled (one day this kid…) by David Wojnarowicz. The innocent, open face of young Wojnarwicz surrounded by the horrors of his future are a hard reminder of the consequences of the lack of civil rights.

On a more domestic but no less socially challenging note, Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian speculate on the shifty language of partnership in their dialectic lyric “Behold the Bride/Groom.” Taking on historical representations of unsanctioned union and desire, Colter Jacobsen’s The Boy’s Book of Magnetism evokes obscure 19th century yearnings and half-memories with illustrative, shadowy graphite, while works by Matt Keegan, Carlos Motta, and Sharon Hayes recall the hard-edged graphic images and brassy identity polemics of the 90’s culture wars. Robert Gober contributes a scrawled off post-it note that begins with “first they came for the gays…” and ends with “so who gives a shit?” Gober’s ironic acid is matched by the sincere tenderness found in Nicolas Paris’s delicately formal Amantes (lovers), Raymond Pettibon’s loose and gentle painting of two hearts No Title (Paint fills them) and sensual portraits of female couples by Nicole Eisenman and Laylah Ali. In a decisive move to reaffirm the project’s agenda, the book concludes with Frank Rich’s editorial writings on gay marriage, Martha C. Nussbaum’s essay on the history and philosophy of marriage, and Untitled (one day this kid…) by David Wojnarowicz. The innocent, open face of young Wojnarwicz surrounded by the horrors of his future are a hard reminder of the consequences of the lack of civil rights.

Even a quick glance through The Air We Breathe affirms that its partner, the SFMOMA show, is a powerful public display––and certainly, one major aspect of the right to marry is the right to legitimate public display. But the deeper side of the issue is the legitimacy of intimacy, both sexual and domestic. It’s here that the print version of The Air We Breathe does its work. We may enter a museum for a public experience, but a book is capable of entering our homes. A book becomes a domestic object that allows words to be lingered over, lines of an image to be traced with the finger. Held in the hands, read in the favorite chair or in a bed still rumpled from lovemaking, The Air We Breathe becomes a series of private conversations. The nearness of voice and vision that pervades the book gives one the feeling that these poets and artists are showing us something private about the intimacy of bodies, about lives learning to join with other lives, about the love and struggle that is at the heart of the marriage equality issue and, of course, marriage itself.

More from Donal Mosher, filmmaker (October Country and an upcoming documentary on Bigfoot, Suicide and God) here