45 More Stories by Donald Barthelme

24.01.08

Flying to America: 45 More Stories

Flying to America: 45 More Stories

by Donald Barthelme

432 pages

Shoemaker & Hoard

(October 28, 2007)

ISBN-10: 1593761724

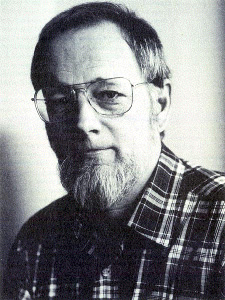

Barthelme. Even the name is strange, with what seems to be a superfluous syllable of mysterious pronunciation dangling precariously from the end. That uncanny flourish, scored into the very meat of language, suits one of the United States’ greatest men of letters. “Man of letters” particularly suits Barthelme: his work’s meaning often resides not in imagery (though his technique birthed it prodigiously, miraculously, the way seeds sprout a garden), but in the semiotic payloads of typographical characters themselves. His stories tended to be short––a couple pages, maybe five or six––which perhaps explains his emphasis on the tiny moving part over the greater mechanism: compression wasn’t a luxury for Barthelme, it was mandatory. And when every letter is a world, you don’t need too many of them to flesh out a cosmos.

This tendency to treat language as an object unto itself, not just a conduit for meaning, is manifest in many of Barthelme’s well-known stories, from “Margins,” where a white square analyzes a black protestor’s handwriting for revelations of his character, to “The President”, in a description of an anklet where “each tiny silver circle held an initial: @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@.” It is also manifest in Flying to America: 45 More Stories, which collects all of Barthelme’s stories not previously collected in 40 Stories and 60 Stories, as well as a few that have never been published.

In “You Are as Brave as Vincent Van Gogh,” Barthelme makes fireworks for us:

* ! * !] * !! * [! * ! * and * % % * +&+&+ * % % *

And in “This Newspaper Here,” Barthelme, who’d amassed newsroom experience as a reporter at The Houston Post, again blurs the line between form and content, signifier and significance. “Sometimes on dull days,” he writes, “the compositors play which makes paragraphs like…” Then a block paragraph of patterned punctuation. In “Van Gogh”, text on a page mimics fireworks in the sky, and those fireworks, once established as such, reappear in another story to mimic words on a page. It’s a revealing alchemy from a writer whose wordplay always strived toward the pyrotechnic, by way of diacritical orgies or sonorous puns (such as the “verymerrywine” sipped in this volume).

In “The Big Broadcast of 1938,” Barthelme hums a few bars in a common parlance that, with pointedly chosen syllables, pay homage to a conceptual movement whose assaults on convention paved the way for his own, which, through sheer brio, would find a frequent home in that bastion of traditional fiction, The New Yorker: “da-da, da da da da da da da-a.” And Perpetua, a character who appears in several of these stories (most notably the title story and the one that takes her name) is named for a typeface: one whose elegant slenderness of form alludes to her legendary beauty. Literally “legendary”: the title story begins the volume with a riff on The Iliad’s opening lines:

Sing, goddess, the brilliance of Perpetua, who came then to lend her salt-sweet God-gift beauty to the film. Sing the beauty of the breasts of Perpetua, like unto the cancelment of action at law against you, sing the redness of her hair, like unto the anger of Peleus’ son who put pains a thousandfold upon the Achaeans.

But Perpetua is more than an object of desire: she’s also a revolutionary, a trumpet player in the New World Symphony Orchestra. Revolution and desire are close kin, and they are the twin engines that animate almost all of Barthelme’s writing (the stories in this volume are particularly taken up with the conceptual emancipation of various marginalized groups, particularly women and the elderly). His novel The King was located at such a pivot, between archaic chivalry and modern technological warfare, as was Snow White, positioned between entrenched patriarchy and burgeoning feminism. Numerous stories in Flying to America––“The Piano Player,” “The Bed,” and “You are Cordially Invited,” just to name a few––reside in the same sort of interstice, hanging not on the moment of epiphany but the one just before it, with an effete construct on one side and terrifyingly unknown one on the other. And it’s worth noting that the Perpetua typeface harks back to the transitional style, the high contrasts and horizontal serifs that bridged archaic typefaces and modern ones––a period, in other words, of typographical upheaval, the nebulous in-between space––whether between life-stages or between cultural revolutions––that so much of Barthelme’s writing inhabits. In this way he draws Perpetua the revolutionary and Perpetua the object of desire in one deft, coded stroke.

But Perpetua is more than an object of desire: she’s also a revolutionary, a trumpet player in the New World Symphony Orchestra. Revolution and desire are close kin, and they are the twin engines that animate almost all of Barthelme’s writing (the stories in this volume are particularly taken up with the conceptual emancipation of various marginalized groups, particularly women and the elderly). His novel The King was located at such a pivot, between archaic chivalry and modern technological warfare, as was Snow White, positioned between entrenched patriarchy and burgeoning feminism. Numerous stories in Flying to America––“The Piano Player,” “The Bed,” and “You are Cordially Invited,” just to name a few––reside in the same sort of interstice, hanging not on the moment of epiphany but the one just before it, with an effete construct on one side and terrifyingly unknown one on the other. And it’s worth noting that the Perpetua typeface harks back to the transitional style, the high contrasts and horizontal serifs that bridged archaic typefaces and modern ones––a period, in other words, of typographical upheaval, the nebulous in-between space––whether between life-stages or between cultural revolutions––that so much of Barthelme’s writing inhabits. In this way he draws Perpetua the revolutionary and Perpetua the object of desire in one deft, coded stroke.

Barthelme. The name contains a swarm of associations: foundational postmodernist, acrobatic humorist, formal renegade, satyr and satirist, mordant cultural critic and steel-eyed prophet (this is a man who predicted reality TV some three decades before its advent, in the menacingly surrealistic story “Shower of Gold”). Not an aloof writer––when you read him, he might as well be sitting on your shoulder, chuckling into your ear, with his Amish beard and long bright gaze. His writing is at once exceptionally mannered and exceptionally raw––the cross-pollination of his vast erudition and mercurial spirit–nearly every effort an obvious product of urgent inspiration, “at night,” as he says in “Among the Beanwoods,” “in a rage, slapping myself, great tremendous slaps to the brow which will fell me to the earth.” (Incidentally, while he’s known as a fiction writer, anyone who says that Barthelme was not a poet is a liar who must have the soul of an investment banker.) “Among the Beanwoods” conjures the same sort of glittering dream diorama we might find in Russell Edson, or, more recently, Sabrina Orah Mark:

I am, at the moment, seated. On a chair in the forest, listening. I will rise, shortly, to hold the ladder for you. Every beanwood will have its chandelier scattering light on my exercise machine, which is made of cane. The beans you have glued together are as nothing to the difficulty of working with cane, at night, in the dark, in the wind, watched by insects. I will not allow my exercise machine to be photographed. It sings, as I exercise, like an unaccompanied cello. I will not allow my exercise machine to be recorded.

Flying to America displays the full range of Barthelme’s style: “Edward and Pia” is Joycean stream-of-consciousness, “The Agreement” is an interrogative self-investigation into parental responsibility, “Basil from Her Garden” is a psychological interview, “This Newspaper Here” takes the run-on sentence as its scaffold, “And Then” is an anecdote that becomes an existential parable as Barthelme deftly metes out context. In “Bone Bubbles,” which recalls previously collected works like “Alice,” he abandons the conceit of prose entirely, striking a more Steinian posture: imagistic scraps tremble and shatter into strings of pure glossolaliac verbiage, only to coagulate into image again, in a process perhaps best described as thermodynamic, where meaning can’t sit still:

Flying to America displays the full range of Barthelme’s style: “Edward and Pia” is Joycean stream-of-consciousness, “The Agreement” is an interrogative self-investigation into parental responsibility, “Basil from Her Garden” is a psychological interview, “This Newspaper Here” takes the run-on sentence as its scaffold, “And Then” is an anecdote that becomes an existential parable as Barthelme deftly metes out context. In “Bone Bubbles,” which recalls previously collected works like “Alice,” he abandons the conceit of prose entirely, striking a more Steinian posture: imagistic scraps tremble and shatter into strings of pure glossolaliac verbiage, only to coagulate into image again, in a process perhaps best described as thermodynamic, where meaning can’t sit still:

bins black and green seventh eight rehearsal pings a bit fussy at times fair scattering grand and exciting world of his fabrication topple out against surface irregularities fragilization of the gut constitutive misrecognitions of the ego…

Barthelme’s open-form stories invite reader participation. They demand intimacy and reflection. All but devoid of contiguous social realism (favoring a sort of discordant, aleatoric realism instead), they come to life only within the vault of a radically specific consciousness––yours, mine. They are a hostile microbe within the corpus of narrative convention––and by extension conventional criticism––operating under a set of intuitive and infinitely malleable rules that neither obey nor subvert these conventions. They simply sweep them aside, effectively breaking the rules of the game, which perhaps explains the weirdly personal vehemence with which Barthelme’s detractors revile him. He’s the stage magician who reveals trade secrets at every turn.

We’re so used to being manipulated by fiction that it can be difficult to see what Barthelme’s doing, even as he spells it out in no uncertain terms. The smattering of stories in this volume that are overtly didactic, with exactly one point, emphasize by contrast how differently than the norm Barthelme’s writing usually operates. “Tales of the Swedish Army” is an example of an unusually narrow Barthelme fable: it’s plainly about the dangers of American power in the world, as a good-hearted but bumbling American narrator unwittingly draws a helpful Swedish soldier into all kinds of trouble. This story, with its fixed center, is an anomaly in the Barthelme catalog, which more often leaves the reader feeling at once electrified and somehow tricked. At one point during the writing of this article, I decided I would try to “interview” Barthelme in the attempt to locate the center of his writing. But I only got this far:

Q: Donald B, are you fucking with me?

A: Always, and never.

There are numerous approaches to Barthelme’s work: you can mine its dense thicket of literary, sociological and philosophical allusions. You can exhume the theoretical and political subtexts that are so fundamental to his work. You can celebrate his spirit of play or his otherworldly yet personable voice, a crucible where the colloquial and the fantastic, the commercial and the aesthetic, seamlessly merge. You can parse it as a series of hermetic formal experiments, or outward-looking social criticism, or postmodernism’s archetypal manipulation, for it is all of these things. But these approaches, individually, are insufficient, for inasmuch as a story like “Views of My Father Weeping” (collected in 60 Stories) is a Freudian allegory, it’s equally about a ball of orange yarn hanging motionless in the air (a fillip of stasis that recurs in the title story of this new volume, this time in the guise of a tossed whistle, caught in the syrupy air of Barthelme’s conceptual space): an irreducible sensory experience that discourages exegesis, encourages the silence of deep perception.

There are numerous approaches to Barthelme’s work: you can mine its dense thicket of literary, sociological and philosophical allusions. You can exhume the theoretical and political subtexts that are so fundamental to his work. You can celebrate his spirit of play or his otherworldly yet personable voice, a crucible where the colloquial and the fantastic, the commercial and the aesthetic, seamlessly merge. You can parse it as a series of hermetic formal experiments, or outward-looking social criticism, or postmodernism’s archetypal manipulation, for it is all of these things. But these approaches, individually, are insufficient, for inasmuch as a story like “Views of My Father Weeping” (collected in 60 Stories) is a Freudian allegory, it’s equally about a ball of orange yarn hanging motionless in the air (a fillip of stasis that recurs in the title story of this new volume, this time in the guise of a tossed whistle, caught in the syrupy air of Barthelme’s conceptual space): an irreducible sensory experience that discourages exegesis, encourages the silence of deep perception.

Barthelme’s skill as an aesthetician and humorist was unparalleled, and sometimes, just deliciously snarky: In “Flying to America,” he notes that stars photograph better because they have “bigger heads” than ordinary people, and imagines torturing a would-be trifler by confining him in a small room “with the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen.” But more often, his bon mots bolstered the radical payload of his stories: like Celine before him, he practiced a laughing-to-the-gallows eschatology. He gets off one of his best bits in “Perpetua,” when Harold, who’s become obsessed with the back of a woman he saw in a men’s magazine, writes to the magazine and asks for her address. When the magazine replies, with royal condescension, that it is “not a pimp,” Harold writes back, enraged: “If the magazine was not a pimp, what was it?” Barthelme’s humor is the mortar that holds his deadly serious themes and befuddling formal mutations together.

Yet if you look around 45 Stories, in the creases of the tangled pastiche, you find Barthelme telling us exactly what his concerns and methods are, time and again. “Order is not interesting,” Perpetua says in the title story. “Disorder is interesting.” This maxim, which is wholly Barthelme’s own, is restated in “Henrietta and Alexandra”: “I prefer the inane sometimes. The ane is often inutile to the artist.” In “Paradise Before the Egg”: “It’s natural, when you see a loose end, to pluck at it.” Barthelme was the bard of interstices and slippages, as these passages attest, and even at his most inscrutable, there was something open and honest about his writing, which makes no claims to the imposition of narrative on chaotic human experience, instead palpating is-ness.

“Presents,” one of this volume’s most beautiful and confounding works, is more like a series of performance-art photographs than a story: Naked young women (“one dark, one fair”), Henry James, and “giant eggs” boiling in “red plush chairs” reconfigure from panel to panel, striking one vivid tableau after another while staying a step ahead of discernible meaning. This is not the Barthelme who obliquely harangues on the institutionalized depredations of free will and desire (one of his favorite themes, addressed most directly here in “Pages from the Annual Report,” which evokes “The Game” in its examination of egos disintegrating in the grinding gears of a Kafkan bureaucracy––Barthelme, like Perpetua, is interested in “people who are beset by dark malefic forces”). This is the Barthelme who simply looks. After the pressurized mystery of the scenes has mounted to near-explosive levels, Barthelme, sensitive to the reader’s potential frustration, begins to speak to us directly:

“Presents,” one of this volume’s most beautiful and confounding works, is more like a series of performance-art photographs than a story: Naked young women (“one dark, one fair”), Henry James, and “giant eggs” boiling in “red plush chairs” reconfigure from panel to panel, striking one vivid tableau after another while staying a step ahead of discernible meaning. This is not the Barthelme who obliquely harangues on the institutionalized depredations of free will and desire (one of his favorite themes, addressed most directly here in “Pages from the Annual Report,” which evokes “The Game” in its examination of egos disintegrating in the grinding gears of a Kafkan bureaucracy––Barthelme, like Perpetua, is interested in “people who are beset by dark malefic forces”). This is the Barthelme who simply looks. After the pressurized mystery of the scenes has mounted to near-explosive levels, Barthelme, sensitive to the reader’s potential frustration, begins to speak to us directly:

The nakedness of young women, especially in pairs (that is to say, a plenitude) often produces bliss in the eye of the beholder, male or female. If you have an elbow in your mouth, then you are occupied, for the moment, but your mind often wanders away, toward more bliss, wondering if you should be doing something else, with your arms and legs, so as to provide more static along the surface of the situation, wherein the two (naked) young women lie unfolded before you, waiting for you to fold them up again in new, interesting ways. Oh they are good kids, no doubt about it, and brave and forthright too, and mind their manners and eggs, and have hope and ambitions, and are supportive and giving as well as chilly and austere––most of all, naked. That is a delight, let us confess the fact, and that is why we are considering all these different ways in which naked young women may be conceptualized, in the privacy of our studies, dealt like cards from a deck of thin, flexible, six-foot-tall mirrors.

This passage is pure Barthelmismo: The sudden impenetrable image (“an elbow in your mouth”), the “static along the surface of the situation” (this is where the author lives), the conceptual and the desired posited as self-reflecting quantities. Flying to America brims with the stuff, even given its secondary status in the Barthelme canon. After all, he hand-selected the stories to be collected in 40 Stories and 60 Stories, pointedly omitting these, which leads one to wonder––what did Barthelme wish to conceal about himself, in the final tally? A surprising number of these stories are taken up with troublesome relationships between men and women, whether complicated by age or sexual polygons, and perhaps he wished to downplay this more prosaic (yet still fantastically inventive) part of his sensibility. Flying to America gives us a portrait of a writer struggling with stale marriages and the insults of age, but by including one of Barthelme’s earliest published stories (“Florence Green is 81”) with the one he was working on at the time of his death (“Pandemonium”), it also gives us a writer whose zest remained undimmed for the duration of his lengthy career. “Pandemonium” contains Barthelme’s final published sentences: “I wondered about my colleague. Was he, perhaps, skewed in the brain?” One can’t help but wonder the same thing about Barthelme when submersed in the roiling depths of his consciousness (like the job candidate in “The Reference,” “He warp ever’ which way”) while wishing that such heroically skewed brains were not so rare in American fiction.