Van Dyke Parks’ Song Cycle, an excerpt from the 33 1/3 series

19.10.10

It had been a year since racial tension, long festering in Detroit, gave way to the massive insurrection triggered during the summer of 1967 by the Twelfth Street riot. Twelve months on, the city was visibly in decline; it remains so. In a January 1, 2003 NY Times interview, author and Detroit native Jeffrey Eugenides recalled his hometown’s Jefferson Avenue: “During my whole life, it was crumbling and being destroyed little by little.” He could have been describing the city itself. One simply became accustomed to things getting worse with each passing year, the civic infrastructure becoming ever more neglected and battle-scarred. And, sadly, one got used to the idea that it wouldn’t recover.

It had been a year since racial tension, long festering in Detroit, gave way to the massive insurrection triggered during the summer of 1967 by the Twelfth Street riot. Twelve months on, the city was visibly in decline; it remains so. In a January 1, 2003 NY Times interview, author and Detroit native Jeffrey Eugenides recalled his hometown’s Jefferson Avenue: “During my whole life, it was crumbling and being destroyed little by little.” He could have been describing the city itself. One simply became accustomed to things getting worse with each passing year, the civic infrastructure becoming ever more neglected and battle-scarred. And, sadly, one got used to the idea that it wouldn’t recover.

The city’s core, while still commercially active, had already changed. There was a distinct vibe of “playing in the ruins,” though at its margins there was liveliness in the makeshift retail sector cobbled together by area hippies: the repertory cinema where I sat eating Kentucky Fried Chicken through most of Andy Warhol’s eight-hour portrait of the Empire State Building; faux-Anglo mod clothing boutiques (Hyperbole!); and lots of record stores. Raised on radio, I was drawn to those stores. I was still very much a novice, though, without compass in an ocean of vinyl.

My rounds of a given Saturday often took me to Ross Records, a dingy little shop in downtown Detroit’s Harmonie Park enclave. This was a real record retailer, not merely a series of bins adjacent to where hi-fi gear was sold in a department store like Hudson’s. The store was not so user-friendly as all that; clearly some decoding was in order, prior to making choices. I couldn’t deny the feeling of being stonewalled by a language I didn’t speak. There was much to decipher: the bilious, homely nudes adorning the UK edition of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland; bins filled with “party albums” recorded by Redd Foxx and Moms Mabley, their sleeves darkened and gummy at the edges by years’ worth of fingertips stained with testosterone and malt liquor; unpronounceable musicians credited on Indian records from the World Pacific label; Esperanto liner notes on jazz albums from ESP-Disk and, in ever increasing numbers, those “psychedelic” records.

Record companies were obviously doing a land offce business with the latter. As I was equally new both to the majority of this music and to the FM broadcasts where I might likely hear it, in the store I could only stare at the packaging and play my hunch. The records intended for the growing audience of “heads” had their own visual syntax, the common denominator being minor variations of showy, trendy, self-conscious takes on what passed for “weird” at that point in time — the gnomic visual language of newly stoned musicians recording for newly stoned audiences. The record companies’ art directors, themselves often much older, scotch ’n’ soda types caught up in cracking this code, tended to follow the path of least resistance. Their “psychedelic” look invariably pulled from the same gamut of pastel colors in the service of manufactured bliss. The titles were spelled out in drippy, bastardized Art Nouveau typefaces inspired by The Yellow Book. The musicians might be portrayed as either visiting dignitaries from another planet or Hindu deities, or the mutant products of sex between Visigoths and cowboys, or the inhabitants of a Salvador Dalí landscape. If these bands weren’t from San Francisco, it appeared obvious that they wanted to be.

There seemed to be a constant, lurking subtext having something to do with the musicians in question possessing the Answer. It was as though coded messages pulsed from these sleeves: if you were as loaded as the guys who made the record — and if you bought their record — you would receive the Answer. I bought a few of these records, but not many; I’m still waiting for the Answer. In retrospect, I’m amazed that any of these records, the ones wearing countercultural credibility on their sleeves, spoke to me on any level. It all seemed so forced, even to a tyro like myself.

There seemed to be a constant, lurking subtext having something to do with the musicians in question possessing the Answer. It was as though coded messages pulsed from these sleeves: if you were as loaded as the guys who made the record — and if you bought their record — you would receive the Answer. I bought a few of these records, but not many; I’m still waiting for the Answer. In retrospect, I’m amazed that any of these records, the ones wearing countercultural credibility on their sleeves, spoke to me on any level. It all seemed so forced, even to a tyro like myself.

One Saturday late in 1968, I selected a record (based on little more than the questionable appeal of its graphics) and took it to the cashier. (For the longest time I couldn’t have told you which album I’d initially selected. Perhaps because such notions are still in vogue, repressed memories now figure into my account. The past denied is liable to surface when least expected; so it is that only now do I remember nearly buying something by It’s a Beautiful Day, a band that actually was from San Francisco.) I presented my find to the long-haired guy behind the counter; we had become acquainted over the course of previous Saturdays, as he patiently fielded my questions and endured my opinions.

Dan Turner was regarded as something like a Jedi knight amongst Detroit record clerks. I hesitate when mentioning his ability to summon the minutiae of an artist’s career in an instant, or citing his rhetorical skills in gently flattening a customer’s argument made on behalf of a substandard album from a band Dan knew could do better — to do so is to risk invoking a nerdy stereotype. Dan was nothing like the comic book store guy from The Simpsons, nor did he resemble the cutting, self-impressed characters staffing the shop in the film version of High Fidelity. Rather, he was quick witted and affable, definitely a character but someone with knowledge to impart. Years later, as the ’80s began, mutual friends introduced me to the rock writer Lester Bangs during his final years in Manhattan. My knowledge of him was confined to a couple of conversations. Even so, it appeared that living up to the funny, raunchy, opinionated character Bangs had created for himself in print wasn’t doing much for his health.

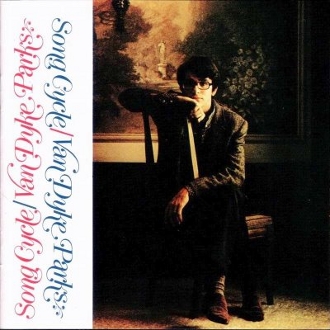

Dan Turner, by contrast, didn’t have to break a sweat — a decade and more before, he already was that character. Dan cast a baleful eye on my choice. Strolling over to the “P” bin, he produced a long player I had failed to notice earlier. The sleeve graphics seemed more appropriate to a poetry paperback than a rock album. There was a photo of the artist, a man named Van Dyke Parks, seated in a dining room chair, a very adult setting rendered in the colors of autumn. His look was best defined as “academic”: tidy haircut, by the measure of the day; tweed sports jacket; suede loafers — though he appeared barely older than I was at the time. The signs and signifiers of his portrait connoted intelligence, that much was undeniable. He did not appear especially au courant, however. Handing me the record, Dan made his point with scant few words, “You’ll be happier with this.”

And so, with little ceremony, Song Cycle entered my life. That Saturday proceeded as several before it had, and as would a great many that came in its wake: I returned home and dropped the disc onto the turntable, expecting to be entertained through the ensuing afternoon. That Saturday afternoon was different, which is one of the reasons I’m writing this book.

Song Cycle established its presence immediately. There was no warming up to it, nor was there any sense of time lost waiting for it to sink in over the course of multiple plays. Its music was nimble-footed, at times appearing slight as gossamer, while its lyrics often alluded to very serious subjects. Sunny and pert, it seemed an album that could only be made by a resident of Southern California. Its lyrics were sung with the exuberance of youth (refreshing, as the average late ’60s artist seemed intent on shouldering a burden of experience out of all proportion to his or her actual age), but these lyrics spoke of troubling subjects: racial inequality and dashed hopes and war and loss. Parks’ songs spelled out many of the hard lessons of history, though often by elliptical means. The music floated between the speakers, a silver cloud with a dark lining.

Song Cycle possessed immediacy and verve and, most importantly, a sense of engagement with the listener. I hadn’t realized, prior to this juncture, the extent to which most of the records I had played were set up to elicit passive responses from their listeners. There was nothing passive about this record. Posing more riddles than the average sphinx, with its decipherable answers pointing somewhere dark, Song Cycle was anything but passive. Seemingly implicit in its design was the beginning of a dialog, as though this Van Dyke Parks (whose name alone intrigued me, and had me wondering if his parents were both painters) was inviting a response from his listeners. Having already seen hippie bands play with their backs to the audience, the thought of late ’60s musicians being interested in their listeners was a concept bordering on revolutionary. It was apparent that Song Cycle was crackling with ideas, seemingly all of them worthy of investigation.

The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band had appeared recently enough that “classically influenced albums” and “concept albums” were being talked up in the papers; this last term, then new to me, indicated several songs linked via an overarching theme. Of course, Frank Sinatra had pioneered the conceptually managed sequencing of his albums as far back as 1954’s In The Wee Small Hours, but even if I’d known that at the time, it would hardly do to remind anyone about Frank Sinatra in the face of the Beatles’ achievement, late ’60s types believing as they did that their music erased the past and purified the cultural playing field. Song Cycle, in welcomed contrast, was a concept album that acknowledged the “better living through chemistry” era into which it had been released as well as the earlier, more romantic era peopled by Sinatra and his generation. In fact, by dint of its plain-spun title, Song Cycle indicated that Van Dyke Parks was comfortable extending his musical purview back to the original “concept albums,” the song cycles of nineteenth-century composers such as Beethoven (his An die ferne Geliebte is considered the seminal song cycle by most) or Schubert (Winterreise). In light of this consideration, rock records that claimed to be “classically influenced” by dint of featuring a cello or a flute seemed somewhat anemic.

Often the links of late ’60s concept albums were made literal in the form of unbanded album sides, whose music played continuously without break. Each of the dozen tracks comprising Song Cycle possessed defined introductions and codas and could play as stand-alone pieces, unlike the songs from Sgt. Pepper’s and its kin, where a song’s boundaries often were smeared with cross-fading and sound effects. But I never played individual tracks from Song Cycle. Indeed, it wasn’t so much a matter of listening to the record as the thought that I viewed it from start to finish, just as I would a film. These songs existed as appropriately integrated melodies and observations within their own right, but the album dictated its own presentation, a testament to the means by which its songs were interlocking modules constituent of a greater entity.

A chain of questions followed by answers: this was how composer and guitarist Lou Reed described the structure of his songs’ placement on the albums recorded by the Velvet Underground. Van Dyke Parks seemed to have something similar in mind, though his discourse was often achieved on a more purely musical level, by addressing the mechanisms of his songs and designing flow and contiguity into melodies that would yield implied connections between his songs and the topics that they broached. It was clear that Parks had an overarching design in mind. The signs were everywhere: an ingenious modulation from one key to another structured as a punning reference to some chestnut of Tin Pan Alley songwriting; the considered relationship between the chord sequence of one song’s coda and the intro that followed; melodies, these sometimes represented only fractionally, resurfacing at intervals; the revolving-door array of instrumental timbres.

The record’s allure was compounded by the intrigue of each song being set in its own virtual landscape, one created with specific textures of echo and reverberation and peripheral sounds — weather, insects, the footfalls and voices of passersby. It was the first time I’d ever taken notice of this aspect of record production. One song described a discovery in the family attic; reaching past previous examples of impressionist composing, the song’s acoustic contours suggested mustiness, rarely visited space, perhaps a lowered ceiling. In time I would read the press generated by Song Cycle, with at least a few of its favorable reviews marveling that Parks played the recording studio as much as he did the piano. Song Cycle introduced me, and doubtless many others who came to regard the multi-track studio itself as an instrument in its own right — and I would certainly include in this number the English polymath Brian Eno, whose solo albums from the ’70s received the same accolade — to the potential of a record’s production to suggest scenery and location, a sense of movement in the shadows.

Song Cycle seemed to play longer than any of the other albums I’d experienced to that point. In fact, at 35 minutes and 30 seconds, it turned out to have a shorter running time than many of my records. Parks was composing in the time-honored sense of the term and, expanding upon that notion, he was composing with the advantages and the limitations of existing technology at the forefront of his consideration. It enhanced the already palpable sense of adventure that informed the whole of this unusual disc, that sense born of the pooled imaginations of Parks, a prodigiously talented artist, his producer, a daring rookie named Lenny Waronker, and his engineers Lee Herschberg and Bruce Botnick, the technicians who, respectively, recorded and mixed the music of Parks’ solo debut.

Needless to add, this resembled nothing that I’d encountered on the radio, nor anything that I’d heard in the collections of other kids I knew who liked music. The only comparisons available to me — and even these connections were tenuous at best — were to the records my father enjoyed. For most adolescents at that juncture in history, such a realization might be a deal breaker, full stop. Luckily for me, it was through his record collection that my father stayed in touch with his inner nonconformist. The crisp diction of Song Cycle’s vocalist was comparable only to the diamond-cutting consonants of jazz singer Blossom Dearie, and the engaging wordplay of Parks’ lyrics reminded me of my dad’s beloved Gilbert and Sullivan operettas (the D’Oyly Carte recordings for which he literally sold blood in order to afford during his college years). There was nothing ostensibly comedic about Song Cycle, though it was undeniably witty. It often moved at a dizzying clip and the painstaking craftsmanship evident in its recording seemed somehow related to the albums of double-time musical slapstick crafted by Spike Jonze and his City Slickers, that successful “novelty act” of the ’50s whose records were in heavy rotation on the paternal hi-fi.

The spit-polished calypso of Harry Belafonte was also heard frequently in our living room, as it was in many homes from the end of the Eisenhower era onward. During those years, when most of the prime movers from the first great era of rock either had died or were neutralized for various reasons, many record company moguls bought into the thought that calypso would emerge as the next vogue in popular listening tastes. That didn’t happen, but it still amazes me to contemplate that from the late ’50s into the early ’60s, Louis Farrakhan, Maya Angelou and the actor Robert Mitchum, among others, tried to launch their respective recording careers by interpreting the popular song forms of Trinidad. Calypso was a transient blip on America’s cultural radar, but it made a lasting impression in my family home, just as it would on Van Dyke Parks, who was introduced to the vivacious sounds of the Caribbean when he was beginning a career as a folk musician in California. Calypso’s fingerprints were untraceable on Parks’ first album, but that music would reassert its thrall at later intervals in his career; again, I had no way to know any of this in the moment of my coming to terms with Song Cycle.

Indeed, what I didn’t know was probably helpful in my engaging directly with this record. The Beach Boys’ singles were a part of my environment as they were everyone’s, but when I first encountered Song Cycle I had no knowledge of Parks’ collaborative involvement with SMiLE, the anticipated masterwork of Beach Boys’ composer/producer Brian Wilson, nor could I have known that SMiLE and Wilson himself were derailed for all intents and purposes by that point. I was unaware of Parks’ resume as a session player, his credits so remarkable for a player barely out of his teens; prior to making Song Cycle, he was already a denizen of Hollywood’s recording studios, contributing to benchmark recordings by Judy Collins, The Byrds, Paul Revere and the Raiders, Tim Buckley and many others.

In short, I was probably an ideal audience for the premiere offering by Van Dyke Parks, budding solo artist. I came to the record without preconceptions. What I lacked in education, I made up for in part with curiosity and open-mindedness. I didn’t need to dance to his music. I didn’t miss the appropriation of blues motifs by excessively amplified guitarists from England, as seemed essential to every other release in that period. I didn’t need it to rock. For my money, if a record could rewrite the laws of physics to suit its own needs, and successfully adhere to those revised laws for the duration of its running time, I’d tag along wherever it led me. I became aware during its first play that Song Cycle would become a constant companion, well before the stylus hit the run-out groove at the end of its B-side. Evidenced from what I heard that Saturday afternoon, Van Dyke Parks seemed happy to be following his own script, heedless of prevailing fashion; it’s nearly impossible nowadays to exaggerate the appeal this quality held in the late ’60s. It certainly worked for me, up to the point when I returned to the store in a vain effort to find more records that sounded like Song Cycle. Unfortunately, there didn’t seem to be any. Four decades onward, I’ll admit to still looking and will attest that there are no facsimiles, reasonable or otherwise, to be had. Desperate — and I can’t believe that I thought this might pay off — I stooped to auditioning albums made by musicians with weird names. This led nowhere in a hurry. Lincoln Mayorga, for instance, was an accomplished keyboardist who also did extensive session work for pop records. I checked out one of his solo LPs, encouraged by the fact of it being released by an audiophile record label, my first encounter with such a thing. Though he played on a Phil Ochs album to which Parks also contributed, I found out in short order that Mayorga did not have a Song Cycle within him. So much for that idea.

Intrinsic to the pop music of my youth was the notion of songs designed as a series of disposable experiences; whether much has changed in that regard during the past 40 years is open to conjecture. Many of the records that I bought during that first year engaged my attention for a matter of weeks, maybe months, and then they were relegated to the shelf, rarely to be revisited. That was fine, as they were intended to do that. Song Cycle represented unfinished business on some level. It demanded repeat visits. In a time when the turnover in fashion, either sartorial or musical, was especially — indeed brutally — rapid, this curious record built with string sections and keyboards and the boyish tenor singing voice of its author often as not would divert my attention from newer records that I’d bought. It would continue to do this for many years thereafter.

Song Cycle was, itself, ostensibly pop music, if only for being released by Warner Bros. Records, a label concerned for the most part with pop music. (The album was provisionally titled Looney Tunes, a nod to the antic cartoons famously associated with Warners’ film division.) I bought many albums during my first year of involvement with recorded music; many of those were on Warners or its affiliated label Reprise (an imprint started by Frank Sinatra in 1960 after his departure from Capitol Records, and three years later sold to Warners). There seemed overall to be a vein of intelligence and risk-taking common to many of the releases from these two labels. Enthusiasts of jazz and classical music had long hewed to their own specific brand loyalties. Through the decade previous to my coming of age, fans of rock and pop had sworn allegiance to Sam Phillips’ Sun Records; a few years later a different crowd would hew to the sunny orange and yellow swirl emblazoned on Capitol Records singles, identifiable with phenomenally popular releases from the Beach Boys or the Beatles. Many of the artists in the Warners/Reprise stable seemed to share an impracticable worldview, at once doe-eyed optimistic and, in the next moment, cynical and dystopian. In other words, Warners seemed like a safe haven for artists with complexity and depth of character, humans whose music as often as not required patience and investment of time on the listener’s part. Yet this music, the stuff of Song Cycle and specific other Warners/Reprise albums released in its wake, was still pop music at core. In the course of trying to puzzle out this conundrum, brand loyalty asserted itself within my own tastes and that of numerous others within my age group. As several record-collecting members of said demographic would in time form their own bands and sign with Warner Bros. Records and move a great many units at retail — R.E.M. comes readily to mind in this context — cultivating their allegiance would pay handsome dividends for the label in the years to come.

In the years that have elapsed since the late ’60s, I have spent much time and energy evangelizing on behalf of my favorite music, just like so many (regrettably, most of them male) members of my birth cohort. It was some- thing that we did, and that some of us still do even now, in an unexamined way. Attendant to this activity is a peculiar inverse ratio of received apathy scaled against passionate intentions, one that describes my lack of success converting others to the cause of artists whom I care most about. My list is different than yours, no doubt, but he frustration is doubtless the same.

Of course, my toughest sell has always been Van Dyke Parks. It’s not like I’m alone in this regard, either. If he wasn’t the first example of that doomed breed known as Cult Artists, adored by critics yet all but ignored by paying customers, he was certainly the best publicized. Song Cycle generated more than its fair share of bouquets — “Charles Ives in Groucho Marx’s pajamas” has long been a favorite — and more than a few brickbats in the press of its day. I’ve pored over many reviews from the time of Song Cycle’s release in the course of researching this book. Reading these, and ignoring history for the moment, it’s easy to assume that the album would write its own ticket with record buyers and Warner Bros. shareholders alike, and that its author’s progress was assured. It didn’t turn out that way. But when I read the reviews that give the impression their writers’ lives had been markedly improved by the existence of Song Cycle, I feel compelled to join the chorus and try to present its case, even at this late date. My attempt to do so may resemble the joke about playing the country and western record backward: Your girl comes back, your dog doesn’t die, your pickup runs like a top and, in this case, your deeply personal wunderkammern of an album becomes a success. I can only try.

Weird but true: during the last couple of decades, the impression is deeply received that European and Japanese audiences appreciate Parks’ solo work more than his own compatriots do. All of his writing has struck me as American to the bone, so much so that I’ve assumed it to be undecipherable by foreign audiences. So when a Dutch street orchestra performs “Jack Palance,” the calypso tune personalized by Parks on his second album, or when Parks is accosted repeatedly on the streets of Tokyo by fans, or when he merits a standing ovation at London’s Festival Hall merely for taking his seat at the world premiere of Brian Wilson’s SMiLE, I’m glad for him — doubtless he knows how it feels to be left on the shelf — but it’s all the more bewildering to me. Once I made reference to Parks during an interview with the English singer-songwriter Robert Wyatt, another personal favorite who’s a tough sell for the uninitiated; in his companionable Home Counties accent, Wyatt stopped me mid-phrase, cautioning: “Careful now — that’s a proper musician you’re talking about.”

As mentioned, I bought many records in 1968. Irrespective of which record company released them, Song Cycle remains the only one purchased then that yields the same amount of satisfaction for me in the present day.

____________________

This excerpt is courtesy of Continuum International Publishing Group. You can learn more about the 33 1/3 series here or purchase a copy of Henderson’s Song Cycle.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

Brian Howe on Joanna Newsom’s Have One on Me

The music films of Animal Collective, John Zorn and chess-playing Canadian hipsters