Enough, enough, enough, enough enough: Perfume Genius’ Unlearning

28.08.10

Since it was noted by Freud in 1914, psychologists have struggled to understand the phenomenon of repetition compulsion in which a victim is compelled to repeatedly act out past trauma, both tangibly and in the mind.

Since it was noted by Freud in 1914, psychologists have struggled to understand the phenomenon of repetition compulsion in which a victim is compelled to repeatedly act out past trauma, both tangibly and in the mind.

REPETITION IS THE BEST WAY TO LEARN, proclaims one aphorism in visual artist Jenny Holzer’s Truisms series and perhaps that’s one way to understand the compulsion. By re-enacting an event mentally or physically, the individual flattens an experience into knowledge. An image, instead of the direct experience, now occupies the hollow part of the mind where intellect quietly sleeps.

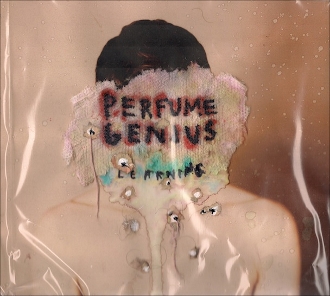

On his debut record Learning, Perfume Genius, a.k.a. Mike Hadreas, seeks vindication from trauma via spatial, textual, and sonic repetition. The 26-year-old Hadreas recorded Learning in his mother’s house in Everett, WA. In an interview with The Line of Best Fit, he describes the process of recording the album: “I started off without any intentions really. It was just sort of a compulsion, almost a therapeutic one. It became a daily thing: writing, recording, making videos. I just had this overwhelming feeling that I was doing exactly what I should be for the first time in my life.”

Many reviewers have written that Learning is a devastatingly sad record—and indeed it is. Perfume Genius shares a similar emotional volatility to their former tour-mates Xiu Xiu. Hadreas’ sings in hushed tones often accompanied only by his own guitar playing or simple piano chords. “I […] always played the piano,” Hadreas has said, “but was really embarrassed of my voice, so I never sang. But a few years ago, after spending a long time alone, I suddenly had something to say and my voice didn’t matter.”

Learning’s songs take place on roundabouts: melodies and tones swirl and recur, as do lyrics. At once, Hadreas’s song lyrics disclose very much and very little, as in the case of the album’s title track, a song built from only five lines of text, leaving mood in the hands of reiteration and rhetoric. “No one will answer your prayers until you take off that dress,” Hadreas sings, perhaps granting new expression to someone else’s disapproval. In the form of a call-and-response, he then addresses the unnamed second person, which may or may not be himself: “You will learn to mind me / you will learn to survive me,” he sings, challenging perhaps both this critic and himself.

Public history and private trauma are intrinsically linked, and Hadreas does a good job balancing his personal despair alongside public events. His songs are well researched and often weave in curious narrative details. Reminiscent of Sufjan Steven’s capsule-biography-in-song “John Wayne Gacy Jr.,” Hadreas’s “Look Out, Look Out” alludes to Mary Bell, a girl from England who, at age 11, was convicted of killing two young boys, one three years old and the other four. The song’s refrain, “Look out, there are murderers about,” refers to a note found in a vandalized nursery during the investigation into Bell’s murder.

The best example of Hadreas negotiating the relationship between public history and private trauma is “Mr. Peterson,” a mournful elegy that expounds on sexual abuse suffered at the hand of a high school teacher. “My work came back from class with notes attached / of a place and time, or how my body kept him up at night,” Hadreas sings. “He let me smoke weed in his truck / if I could convince him I loved him enough.” He pauses for breath. “Enough, enough, enough, enough, enough,” he reprimands himself, as he seeks closure in a hard stop. An emotional turning point follows when Hadreas announces, “When I was 16, he jumped off a building.” This lyric acts as a narrative and emotional hinge, in which Hadreas acknowledges that his disquieting memory is linked to the dead, and that the dead must be forgiven. “Mr. Peterson, I know you were ready to go,” Hadreas eulogizes. “I hope there’s room for you up above—or down below.”

Although Learning is an intimate and morose album, Hadreas does let some light into his songs. He self-reflexively negotiates his own moodiness, rebuking and scolding and sometimes even blatantly mocking his emotionality and predisposition to trauma reenactment. The song “Learning” concludes, “Your father before you and your sister too, your husband blah blah blah blah, you…,” and the piano duet continues; a vocal compression sings “oo-oo-oo” in unison, and the song fades out. Similarly, the album itself concludes with Hadreas chanting “It’s okay, it’s okay,” which is as much a note to self as an expression of reassurance to the listener.

________________________________

Perfume Genius at Matador Records.

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

A Boy Named Xiu Xiu by Mark Gluth

The Queer Child, or Growing Up Sideways in the Twentieth Century by Kathryn Bond Stockton

Stephen Elliott’s The Adderall Diaries: A Memoir of Moods, Masochism, and Murder