A Supposed Return of Disco pt. 1: New York’s House of Slightly Less Jealous Lovers

29.05.08

Perhaps you’ve heard about this hypothetical disco renaissance happening in the abstract downtown of New York, New York. Evidence of some kind of scene includes a jumble of Year 2007 band names, DJs, parties, podcasts, labels, and venues both closed and yet-to-be-opened: Holy Ghost!, Hercules & Love Affair, Shit Robot, Lee Douglas, Metro Area, the Jersey-based label Italians Do It Better, Invisible Conga People, Babytalk, Baby Oliver, DFA, Environ, Justin Miller and Jacques Renault’s Tuesdays at 205, Runaway, Santa’s Party House, Santos Party House, Escort, Arcade Lover, Still Going, Rub-N-Tug, Juan Maclean’s “Happy House,” Studio B, No Ordinary Monkey, Prince Language, People Don’t Dance No More, DJ Spun, APT, Rong Music, Tim Sweeney, 205 Club, My Cousin Roy—to say nothing of the thriving disco edit culture, and to say nothing of LCD Soundsystem’s 45:33 or Sound of Silver or Fabriclive 36. Perhaps you’ve heard about some or all this stuff which yes, at the very least, has some semblance of simultaneity. In my mind then the question is this: Besides whether there is some actual to the hypothetical, for whom is disco making a comeback here? Why is it happening now? What does disco mean anymore anyway?

Perhaps you’ve heard about this hypothetical disco renaissance happening in the abstract downtown of New York, New York. Evidence of some kind of scene includes a jumble of Year 2007 band names, DJs, parties, podcasts, labels, and venues both closed and yet-to-be-opened: Holy Ghost!, Hercules & Love Affair, Shit Robot, Lee Douglas, Metro Area, the Jersey-based label Italians Do It Better, Invisible Conga People, Babytalk, Baby Oliver, DFA, Environ, Justin Miller and Jacques Renault’s Tuesdays at 205, Runaway, Santa’s Party House, Santos Party House, Escort, Arcade Lover, Still Going, Rub-N-Tug, Juan Maclean’s “Happy House,” Studio B, No Ordinary Monkey, Prince Language, People Don’t Dance No More, DJ Spun, APT, Rong Music, Tim Sweeney, 205 Club, My Cousin Roy—to say nothing of the thriving disco edit culture, and to say nothing of LCD Soundsystem’s 45:33 or Sound of Silver or Fabriclive 36. Perhaps you’ve heard about some or all this stuff which yes, at the very least, has some semblance of simultaneity. In my mind then the question is this: Besides whether there is some actual to the hypothetical, for whom is disco making a comeback here? Why is it happening now? What does disco mean anymore anyway?

Disco is not back. Meaning two things. First: True disco culture, as it happened in NYC and San Francisco and elsewhere in the late 70s/early 80s, and as it remains romanticized and pined for by those absent, an uninhibited confluence of pre-HIV intercourse, psychotic drugss, disenfranchised gays and blacks and Hispanics in the midst of self-liberation, record houses flush with rock&roll cash to burn baby burn, kickass soundsystems and impossible dance moves, and (lest we forget) a soundtrack of well-played, well-produced, emotionally raw and utterly danceable positive force tunes we called, as a convenient catch-all, disco—this is not back. Maybe we have the music, and I saw two people make out at the bar once, but it’s not like anybody’s tripping the free bananas or spiking the punch. In a word, there are no more free bananas.

Second: At least in New York City, you’d be hard-pressed to say disco ever really left. Even when Larry Levan’s Paradise Garage shuttered in 87 or something like the Saint in 88, David Mancuso was still finding space for his Loft parties downtown every couple months, and the ex-pats who weren’t on his lists found refuge for their nostalgia in any number of smaller, often outer-borough spots that tried to reproduce the original vibe. Talk to people around for the New York 90s, like Danny Wang, DJ Harvey, Rub-N-Tug, Dan Selzer, Jason Drummond, Morgan Geist of Environ Records, or James Murphy and Tim Goldsworthy of DFA Records, or dig up the risquee flyers advertising parties thrown by Hercules & Love Affair’s Andy Butler, and you’d find out there was still a small but thriving disco subculture happening, with parties like Francois K and Danny Krivit’s Body & Soul, Bang the Party at Frank’s, and the list goes on. Plus it’s worth remembering that first-wave disco music persisted through house and hip-hop samples, while disco’s scientific edge, i.e. its interest in the physics of sound and the pursuit of pleasure via specific interactions of sound, light, and contraband, played out for worse or better in rave culture.

That said. There is a certain stripe of New York, despite the gusto with which the straight white rich have forced out the rest of us, despite Giuliani’s anti-cabaret legislation that, not-kidding, made it illegal to dance, despite all the articles advocating mass exodus to Berlin, despite the grass undeniably being greener and the times having passed us by, there is a stripe of young New York that has embraced the hope and positivity and earnestness of disco. For this crowd it has been a very natural progression, beginning with an interest in postpunk, then into the danceable hybrid strains of no-wave, aka death disco, then into electro-rock and disco-punk, then into straight-up disco tracks I heard just two nights ago, when Don Armando’s “Deputy Of Love” came on at Supreme Trading, a Williamsburg bar that wouldn’t have touched the thing even a year ago. The ripples continued in 2007 with the names I checked above, and now are reaching new heights with what I consider some of late 2007 and early 2008’s truly disco releases: Hercules & Love Affair’s debut LP, Juan Maclean’s “Happy House,” Metro Area’s “Read My Mind,” Holy Ghost’s “Hold On,” Lee Douglas’s “New York Story,” Escort’s “Starlight,” Jacques Renault’s “Magic Games,” Invisible Conga People’s “Cable Dazed,” and who knows what else is in store. These are popular dance tracks succeeding in indie-dance type crowds on their own terms, without what I’d call the macho crutch of rock. Flying in the face of everything you’ve heard about this city, these songs aren’t particularly fashion-forward in the way electroclash was, nor are they sonically conflicted in the way better disco-punk tracks like the Rapture’s “House of Jealous Lovers” or LCD Soundsystem’s “Yeah” so meticulously recombined punk and disco. What they have in common is positivity, a tenacious sort of hope, and a response to the implicit dare James Murphy made five years ago in a song called “Beat Connection”:

That said. There is a certain stripe of New York, despite the gusto with which the straight white rich have forced out the rest of us, despite Giuliani’s anti-cabaret legislation that, not-kidding, made it illegal to dance, despite all the articles advocating mass exodus to Berlin, despite the grass undeniably being greener and the times having passed us by, there is a stripe of young New York that has embraced the hope and positivity and earnestness of disco. For this crowd it has been a very natural progression, beginning with an interest in postpunk, then into the danceable hybrid strains of no-wave, aka death disco, then into electro-rock and disco-punk, then into straight-up disco tracks I heard just two nights ago, when Don Armando’s “Deputy Of Love” came on at Supreme Trading, a Williamsburg bar that wouldn’t have touched the thing even a year ago. The ripples continued in 2007 with the names I checked above, and now are reaching new heights with what I consider some of late 2007 and early 2008’s truly disco releases: Hercules & Love Affair’s debut LP, Juan Maclean’s “Happy House,” Metro Area’s “Read My Mind,” Holy Ghost’s “Hold On,” Lee Douglas’s “New York Story,” Escort’s “Starlight,” Jacques Renault’s “Magic Games,” Invisible Conga People’s “Cable Dazed,” and who knows what else is in store. These are popular dance tracks succeeding in indie-dance type crowds on their own terms, without what I’d call the macho crutch of rock. Flying in the face of everything you’ve heard about this city, these songs aren’t particularly fashion-forward in the way electroclash was, nor are they sonically conflicted in the way better disco-punk tracks like the Rapture’s “House of Jealous Lovers” or LCD Soundsystem’s “Yeah” so meticulously recombined punk and disco. What they have in common is positivity, a tenacious sort of hope, and a response to the implicit dare James Murphy made five years ago in a song called “Beat Connection”:

And nobody’s falling in love/

Everybody here needs a shove/

And nobody’s getting any touch/

Everybody thinks that it means too much/

And nobody’s coming undone/

Everybody here’s afraid of fun/

And nobody’s getting any play/

It’s the saddest night out in the U.S.A.

***

The first time I heard Holy Ghost!’s “Hold On” was early into the night of February 10, 2007, at DJs Dave P and JDH’s popular Fixed party at Studio B. Over the last few years the peaktime vibe of Fixed has switched up from more melodic electro and disco-friendly rock a la Erol Alkan’s Trash parties to harder, tougher-sounding French-filter-metal type fare; the crowd the party attracts has changed along with the metamorphosis. That night’s guest was Lindstrøm, who was to perform a live set sometime after midnight—which is to say most people weren’t there yet for early DJ Tim Sweeney’s set, and the people there weren’t exactly revved up yet. But then Sweeney played this song. The main figure, this skittering synth with a chilly Ghostbusters-like feel to it and a big kick, the chorus awash in confident clavinet chords and breathy pretty-boy vocals—there was this lightning rod-type effect that zapped people onto the floor, a jolt of blindsiding positive energy, something I’ve imagined happening but never seen anything like it. A line seven- or eight-deep waited on the side of the big booth, only to ask Sweeney what he was playing, the song whose lyrics went:

The first time I heard Holy Ghost!’s “Hold On” was early into the night of February 10, 2007, at DJs Dave P and JDH’s popular Fixed party at Studio B. Over the last few years the peaktime vibe of Fixed has switched up from more melodic electro and disco-friendly rock a la Erol Alkan’s Trash parties to harder, tougher-sounding French-filter-metal type fare; the crowd the party attracts has changed along with the metamorphosis. That night’s guest was Lindstrøm, who was to perform a live set sometime after midnight—which is to say most people weren’t there yet for early DJ Tim Sweeney’s set, and the people there weren’t exactly revved up yet. But then Sweeney played this song. The main figure, this skittering synth with a chilly Ghostbusters-like feel to it and a big kick, the chorus awash in confident clavinet chords and breathy pretty-boy vocals—there was this lightning rod-type effect that zapped people onto the floor, a jolt of blindsiding positive energy, something I’ve imagined happening but never seen anything like it. A line seven- or eight-deep waited on the side of the big booth, only to ask Sweeney what he was playing, the song whose lyrics went:

Why do the good things happen in the past /

Streamline the news and trim the fat /

I love the city but I hate my job /

And this old city loves me back

Hold tight, don’t make no plans /

And don’t talk, don’t say no words /

And be still, now move like this /

And hold on, until it kills.

These are really simple words, nude and brutally honest and not particularly cool ones, delivered as both this admission of the city’s more exciting days and a refusal to let its current incarnation keep them down, “a scream inside a scream” too, as if to acknowledge the triteness of this very sentiment to begin with. “They’re all vaguely melancholy,” says Nick Millhiser of his bandmate Alex Frankel’s lyrics, over drinks at Williamsburg’s Roebling Tea Room. “But at the same time not brooding, oddly optimistic in their melancholy.”

Millhiser and Frankel played together in the New York hip-hop sextet Automato, whose Capitol debut was curiously produced by the DFA’s James Murphy and Tim Goldsworthy. “We kinda doubted they knew rap, and they kinda doubted that we knew anything at all,” says Frankel. Between looking for records to sample for new instrumentals and Murphy/Goldsworthy pushing music on them, Frankel and Millhiser came across a ton of disco records. “It would be, ‘I actually like this four-minute track even though I shouldn’t,'” Frankel explained. After Automato broke up, Millhiser and Frankel continued working together on instrumentals at more danceable tempos, keeping friends James Murphy and Juan Maclean abreast of their progress.

The song, at first just Millhiser’s initial rhythm and synth intro loop, was stuck forever in quadruple limbo: Frankel couldn’t figure out the right words or vocal melody until they threw down wurlitzer and clav tracks a year later; Murphy and Goldsworthy and engineer Eric Broucek remain perfectionists when it comes to the recording and production process; Murphy himself was on the road touring Sound of Silver; the song itself was a chancy record for DFA to begin with. “It’s very positive, that track, kinda risky in a way,” says labelhead Jon Galkin at the label offices in West Village. “They really put themselves out there, and it’s pretty easy to get knocked down hard. It’s a lot easier to put out an instrumental track and be safe about it in the world of techno or electro. You know the rulebook. There’s a lot not to be tasteful about when you’re making a real pop song like that, doing real vocals, and I think people responded to that.”

***

Tim Sweeney, the young New York-based DJ who trumpeted “Hold On” before it was released—whom Holy Ghost! credit as “a huge reason” the song ever came out—might not be the architect of the new disco sound, but he’s documented its genesis through his Beats In Space podcasts over the last year. His January 8, 2008 show, which was a rundown of his favorite 2007 tracks, bore witness to songs with the same positive, oddly hopeful attitude found in “Hold On”—what Millhiser called “the light at the end of the tunnel.” It’s different from the late 70s/early 80s sort of positivity, in which the music’s energy was an escape from the popular acrimony existing for toward gays, blacks, and Hispanics in the country—so I wonder if this new disco’s new positive attitude is born rather of the city’s mounting socioeconomic anxieties, and the extent to which this locks up the city’s musically creative opportunities, which typically have required, among other things, cheap rent and commercially indifferent ears. Just going through Sweeney’s January 8 playlist, you can hear the hope in melancholy: Hercules and Love Affair’s “Athene”, whose smoothed-out Arthur Russell vibe might as well be disco shorthand for “hope in melancholy”; LCD Soundsystem’s “45:33 Part 1,” an ode to Celestial Choir’s self-explanatorily positive gospel-disco tracks “Stand On The Word”; Baby Oliver’s electro-funk number “Shot Caller”, a brash and campy novelty-like track though without the safeguard of irony; Lee Douglas’s monstrous big room instrumental “New York Story”; Juan Maclean’s “Happy House”; Invisible Conga People’s “Cable Dazed.”

Tim Sweeney, the young New York-based DJ who trumpeted “Hold On” before it was released—whom Holy Ghost! credit as “a huge reason” the song ever came out—might not be the architect of the new disco sound, but he’s documented its genesis through his Beats In Space podcasts over the last year. His January 8, 2008 show, which was a rundown of his favorite 2007 tracks, bore witness to songs with the same positive, oddly hopeful attitude found in “Hold On”—what Millhiser called “the light at the end of the tunnel.” It’s different from the late 70s/early 80s sort of positivity, in which the music’s energy was an escape from the popular acrimony existing for toward gays, blacks, and Hispanics in the country—so I wonder if this new disco’s new positive attitude is born rather of the city’s mounting socioeconomic anxieties, and the extent to which this locks up the city’s musically creative opportunities, which typically have required, among other things, cheap rent and commercially indifferent ears. Just going through Sweeney’s January 8 playlist, you can hear the hope in melancholy: Hercules and Love Affair’s “Athene”, whose smoothed-out Arthur Russell vibe might as well be disco shorthand for “hope in melancholy”; LCD Soundsystem’s “45:33 Part 1,” an ode to Celestial Choir’s self-explanatorily positive gospel-disco tracks “Stand On The Word”; Baby Oliver’s electro-funk number “Shot Caller”, a brash and campy novelty-like track though without the safeguard of irony; Lee Douglas’s monstrous big room instrumental “New York Story”; Juan Maclean’s “Happy House”; Invisible Conga People’s “Cable Dazed.”

“I feel like there’s something really warm and positive in a lot of those records you mentioned, not in an overbearing, ‘Let’s Celebrate!’ way, but in a more relaxed, comfortable, less self-conscious way,” writes Justin Simon in an email. Simon, along with Eric Tsai, records for the Italians Do It Better label as Invisible Conga People. “I definitely feel that way about James’s thing [45:33]. Somehow it doesn’t sound like it was painstaking to make, even though it sounds really complete and full. I get a good feeling from records like that, where it seems like the artist is comfortable with his or her aesthetic and enjoying making music, rather than coming off as trying to pull a fast one on you, or trying to make a buck or something. I definitely feel it in the new Juan song too. That song is all positivity. And I think one of the reasons [Brooklyn disco act] Escort is so successful is because there’s not a trace of irony in their music. It has a sort of femininity or sensitivity to it, or at least doesn’t come across as macho or ‘bad’ aggressive (as opposed to ‘good’ aggressive). Maybe male New York is getting in touch with its feminine side?”

Which is to say if we’re approaching a new definition of New York disco, though these tracks come from vastly different places sonically, maybe there does exist a similar attitude among them. “It’s so hard to have a sound of the city because of the internet,” says Sweeney at a Flatbush bar this past February. “Everything’s local all at once. I think it’s kind of sad because there’s rarely any DC go-go, Baltimore club-type scene sounds. But it’s interesting because it has since happened here in New York. (There are people in London doing similar things too.) When you’re giving music to your friends, when you’re making music, trying to impress your friends, see what their reaction is—if your friends are everyone that we just mentioned, I think there’s going to be some correlation between sounds. Although I think everyone’s always trying to do something new too. I don’t think Morgan [Geist]…Morgan’s always gonna want to be onto some other thing, still be a step ahead.”

Speaking of Geist: “I see no common ground among half of this stuff,” he writes over email. “Superficially, yes, but as someone who makes music and listens to music carefully I just can’t sense it… As far as heart-on-sleeve, I think some of it has that, and some of it doesn’t. It’s personal. A lot of new music, I don’t feel the earnestness. It’s something you sense. I don’t sense it. Sometimes I don’t sense the earnestness in my own shit, even though I think it’s there. It’s hard to quantify.” Geist, along with Metro Area’s Dharshan Jesrani, Dan Balis and Eugene Cho from Escort, John Selway, Jason Drummond aka DJ Spun, and Rong artists like Lee Douglas, Danny Wang when he lived in New York, Rub-N-Tug’s Eric Duncan and Thomas Bullock––as much as their music fits into the vibe Sweeney identifies, these acts seem either to be predating it or simply existing outside of it. As Geist writes, “My most precious moments with music have been alone, concentrating on the music itself. I’m not a club person.”

Speaking of Geist: “I see no common ground among half of this stuff,” he writes over email. “Superficially, yes, but as someone who makes music and listens to music carefully I just can’t sense it… As far as heart-on-sleeve, I think some of it has that, and some of it doesn’t. It’s personal. A lot of new music, I don’t feel the earnestness. It’s something you sense. I don’t sense it. Sometimes I don’t sense the earnestness in my own shit, even though I think it’s there. It’s hard to quantify.” Geist, along with Metro Area’s Dharshan Jesrani, Dan Balis and Eugene Cho from Escort, John Selway, Jason Drummond aka DJ Spun, and Rong artists like Lee Douglas, Danny Wang when he lived in New York, Rub-N-Tug’s Eric Duncan and Thomas Bullock––as much as their music fits into the vibe Sweeney identifies, these acts seem either to be predating it or simply existing outside of it. As Geist writes, “My most precious moments with music have been alone, concentrating on the music itself. I’m not a club person.”

Sweeney’s relationship to DFA began prior to the label’s founding: He DJed the early slots at an East Village bar on 3rd Street called Plant Bar. Known for playing a lot of postpunk and no-wave on the speakers, Plant Bar was, in a way, the Who’s Who Ground Zero for a lot of the disco-unfamiliar downtown’s future re-embrace of disco: Luke Jenner, the lead singer of the Rapture, was a Plant Bar bartender; Dan Selzer, who runs Acute Records, spun postpunk and no-wave and disco from the booth; James Murphy, who installed the Plant Bar soundsystem, DJ’d there with Tim Goldsworthy; Marcus Lambkin, aka Shit Robot, who was a co-owner; Dominique Keegan, another co-owner, who put out the Sound of Young New York compilations; DFA recording engineer Eric Broucek who, not knowing anybody there, just happened to hang out at Plant Bar during his college days at New York University; Jon Galkin, who credits his first night at Plant Bar as a major inspiration for DFA Records. The Rapture’s work with the DFA, particularly “House of Jealous Lovers” and “Out of the Races and Onto the Tracks,” one could reasonably say were the product of this sort of environment where rock and dance and krautrock and hip-hop and funk were precariously inhabiting the same space. “I remember going and listening to [James Murphy’s] set, and being taken aback by what he was playing,” says Galkin. “I knew what he was playing but it was being recontextualized for me.”

***

I bring all this up because, hindsight being hindsight, it’s fairly obvious how much the DFA helped midwife New York’s greater interest in straight-up unadulterated disco, largely by straddling indie rock and dance in oddly trustworthy terms, and crucially right at a time when indie rock audiences were opening up to non-indie rock music. It could have backfired but it didn’t. Murphy was fluent in rock’s production vocabulary from working with Bob Weston; Goldsworthy, a co-founder of the UK-based Mo’ Wax label, had deep knowledge of house and techno and funk music, further well-documented in his sample-heavy productions for Unkle and other David Holmes affairs; Galkin, who lived in Chicago for the tail end of house and acid house, remembers sneaking into clubs as a teenager. There was something beguiling about the label’s goals—something that inspired some of their future employees to seek them out. “I took baby steps away from rock,” says Justin Miller, who works as DFA’s assistant label manager and DJs alongside Jacques Renault. After hearing “House of Jealous Lovers,” Miller, who was working at a record store in Long Beach, California at the time, “fantasized about coming to DFA, just dropping on their doorstep.”

Eric Broucek, who was studying at NYU at the time and now serves as the DFA’s primary assistant engineer, says the DFA was “a big eye opener.” An intern for Philip Glass at the time, Broucek said over coffee in West Village that he “felt like the label was speaking right towards where I was going, combining all these things I was getting into, these rocky rhythmic bands. I was excited to see how all these cheesy dance moves were done, even if I didn’t necessarily love the context they were used in. Cutting and sampling, quantitizing, treating live music more like a DJ would use it, in terms of EQing or drum sounds to really have a physical presence, I was learning how to make the most effective physical picture that makes you want to dance.”

The extent to which I realized people really go for DFA, really trust Murphy especially, was at an LCD Soundsystem afterparty at 205 Club, a vaguely exclusive two-floor club-lounge in the Lower East Side, after the band’s second show at New York’s Bowery Ballroom. Murphy and Pat Mahoney came down to the basement floor sometime after midnight, and worked his way to the DJ stand cramped in the back corner near the bathrooms, surrounded by Andy Butler, Eric Duncan from Rub-N-Tug, Jacques Renault of Runaway, and played a number of disco tracks that would make their way onto the DJ duo’s Fabriclive 36 mix: the Theo Parrish edit of GQ’s “Lies”, Mouzon Electric Band’s “Everybody Get Down,” Punkin’ Machine’s “I Need You Tonight.” To an extent there was an element of celebrity DJness to the event, but what struck me was that the LCD Soundsystem show I had seen the night before had been very much a rock show, very fierce, to some extent almost fratty how the movements were less about the groove, much about the violence. The basement was packed and yet despite what was a 100% disco night, the crowd totally trusted Murphy’s selections, went nuts with him and danced, until the place was so packed that yours truly had to dance on top of a floorspeaker the whole night.

The extent to which I realized people really go for DFA, really trust Murphy especially, was at an LCD Soundsystem afterparty at 205 Club, a vaguely exclusive two-floor club-lounge in the Lower East Side, after the band’s second show at New York’s Bowery Ballroom. Murphy and Pat Mahoney came down to the basement floor sometime after midnight, and worked his way to the DJ stand cramped in the back corner near the bathrooms, surrounded by Andy Butler, Eric Duncan from Rub-N-Tug, Jacques Renault of Runaway, and played a number of disco tracks that would make their way onto the DJ duo’s Fabriclive 36 mix: the Theo Parrish edit of GQ’s “Lies”, Mouzon Electric Band’s “Everybody Get Down,” Punkin’ Machine’s “I Need You Tonight.” To an extent there was an element of celebrity DJness to the event, but what struck me was that the LCD Soundsystem show I had seen the night before had been very much a rock show, very fierce, to some extent almost fratty how the movements were less about the groove, much about the violence. The basement was packed and yet despite what was a 100% disco night, the crowd totally trusted Murphy’s selections, went nuts with him and danced, until the place was so packed that yours truly had to dance on top of a floorspeaker the whole night.

***

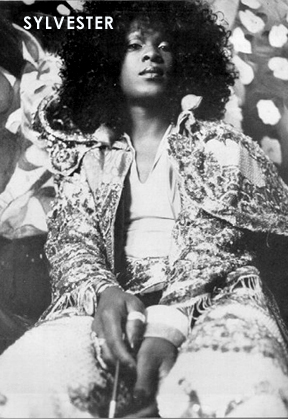

What’s weird to realize is that Hercules & Love Affair’s Andy Butler, who shared DJ duties that night with Murphy and Mahoney and others, came to DFA at maybe the only time the label might have been able to put out records like his––so clearly steeped in dance music, with no rock training wheels, what you might have expected Geist to put out on Environ. Butler’s album is tremendous. Not all the tracks are peak numbers but all of them have what Broucek calls physical presence. As you’d gather from the name of the project, Hercules is both macho-sounding but extremely feminine, sexually charged in a way that channels the early disco’s sensuality, —think Sylvester’s “I Need Somebody To Love Tonight.” “Hercules’ Theme” is, in fact, a theme, a display of the rich sonic contradictions that play out on the rest of the album: alpha-male funk octaves in the bassline next to the breathy male moans, discordant counterpoint chromatic runs on the horns next to a bright and peacocky trumpet solo. The smoothed out “Athene” deals in the same, except with a twist: Athene is the goddess of victory and in-war asskicking, a woman but also a “warman”, which is to say vocalist Kim Ann is “singing a woman/warman’s song.” There’s something virginal about the track too though, desexualized, parthenene. The most swaggering, biggest-beat toughest-sounding house song,”You Belong”, is an admission of defeat: “You belong to him tonight/ there is nothing I can do.”

This being an impossibly smart DFA full-length, explicit sonic references bubble underneath. My favorite is in “Time Will”, which deploys an echo of Frankie Knuckles’s “Your Love” at the bridge, while the vocal harmonies of last track “True False, Fake Real” make a more general reference: So many disco records, even the ones with the terrible bridges, had seriously kick-ass session players behind them. Technically talented musicians played even the cheesiest Philly International string swoops. Granted, the bank to put together a proper disco record is difficult to come by anymore, but Butler, working closely with DFA producer Tim Goldsworthy, enlisted a number of session players for these songs, which are stuffed with sounds and rhythms but the whole thing is mixed and arranged well too: Lush, ready for the Big Room, yet the songs don’t suffer from any kind of claustrophobia. The album is a bold statement, rooted in the past but wholly modern-sounding, to such an extent that you get the sense DFA has always been angling to put out their Hercules & Love Affair, that “House Of Jealous Lovers” and “Losing My Edge” and “Yeah” and everything else was the honey to ready their audience for such blindingly life-affirming music.

***

On March 1, 2008, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, in conjunction with the DFA, hosted the opening party for their Color Chart exhibition, which featured artwork from 1950 onwards that explored the use of color since it became a mass-produced and standardized entity, cf. the commercial color chart. Partygoers were encouraged to wear bright-colored clothing; Jonathan Galkin arranged for the bright lightboxes used in LCD Soundsystem’s “Movement” video to be used in conjunction with the museum’s de facto dancefloor, in the side atrium. The event was sold out, with people on Craigslist offering up to $50 for a scalped ticket. Justin Miller and Jacques Renault, Holy Ghost!, Tim Goldsworthy and Tim Sweeney, and the Juan Maclean were DJs for the night––though one thing that’s worth pointing out, since I’ve been to a bunch of MoMA openings and special events thrown by MoMA’s junior staff Poprally, is that a majority of people come for the art and the free drinks and the possibility of free food and (for lack of a better word) the event’s eventness––not necessarily for the music.

Around midnight, right when Tim and Tim finished up their set and ceded the floor to Juan Maclean, the last record they put on was Dubtribe Soundsystem’s “Do It Now,” whose keyboard and bass figures bear more than resemblance to Juan Maclean’s own “Happy House”—easily the best record of 2008 so far. It was a bit of a gag, one that Sweeney’s done before in his Beats In Space sets, but it left Juan no choice except to play along and put on his “Happy House,” which would come out the following Tuesday. The song’s main two-chord riff, played on a Wurlitzer by Holy Ghost!’s Frankel, resolves into itself but never completely, and so the riff has this propulsive effect, creates this bliss that, musicologically speaking, knows no end. After minutes of build, and after we hear whispers of “bring it back… bring it back…”, vocalist Nancy Whang launches into the verse:

Around midnight, right when Tim and Tim finished up their set and ceded the floor to Juan Maclean, the last record they put on was Dubtribe Soundsystem’s “Do It Now,” whose keyboard and bass figures bear more than resemblance to Juan Maclean’s own “Happy House”—easily the best record of 2008 so far. It was a bit of a gag, one that Sweeney’s done before in his Beats In Space sets, but it left Juan no choice except to play along and put on his “Happy House,” which would come out the following Tuesday. The song’s main two-chord riff, played on a Wurlitzer by Holy Ghost!’s Frankel, resolves into itself but never completely, and so the riff has this propulsive effect, creates this bliss that, musicologically speaking, knows no end. After minutes of build, and after we hear whispers of “bring it back… bring it back…”, vocalist Nancy Whang launches into the verse:

You came to me from my history/

To sweep all the dust away/

Well I never thought I would see today/

So I thank you just for being so damn/

excellent

You are so excellent

You saved me from a rainy day/

Melted all the clouds in the sky/

Yes I always wish it could be this good/

So I thank you just for being so damn/

excellent

You are so excellent

The crowd, dancing when not mugging for event photos, who nonetheless had bought into the disco- and disco-house heavy sets at least since Hercules’s “Blind” had come on an hour earlier, was (or what I’ve realized was) as close to excited as this young, hip, mostly intelligent, mostly straight and white New York crowd can get given the space-time they’re working with. The last words on the last song of Murphy’s last album came to mind:

Take me off your mailing list/

For kids that think it still exists/

Yes for those who think it still exists/

Maybe I’m wrong/

And maybe you’re right

Except that night Murphy was DJing in Paris.

*photo from Polish Sausage Queen’s Flickr