The Zombie Monologues

30.10.09

On a blissful Saturday afternoon late in the summer of ‘sixty one, while entranced by the cathode-ray transmissions of the one-eyed sailor with the smoked-ham biceps, bladder jaw and segmented chin, my mother padded into our living room in a frayed chemise, her feet bare and gray with ash, stood in front of the screen of our bulky black & white, and announced we were going to watch a ‘spooky movie’.

On a blissful Saturday afternoon late in the summer of ‘sixty one, while entranced by the cathode-ray transmissions of the one-eyed sailor with the smoked-ham biceps, bladder jaw and segmented chin, my mother padded into our living room in a frayed chemise, her feet bare and gray with ash, stood in front of the screen of our bulky black & white, and announced we were going to watch a ‘spooky movie’.

To my considerable annoyance, she turned the dial to WNEW’s channel five. And, as Popeye pummeled Bluto into coo-coo bird stupidity, the carnival gaiety of trilling pipe-whistles abruptly gave way to the foreboding thrum of jungle drums. A ‘kooky’ New Yorker-style graphic of turtle-necked beatniks hobnobbing in an espresso bar with disk-lipped cannibals displaced Popeye’s pinwheel of spinach-fueled punches. Clouds of cigarette smoke coalesced in cross-fade into the legend, Drive-in Jungle Jive on Five.

A peevish scowl crinkled my brow. I’m missing Popeye for this?

Now, I had never seen a ‘spooky movie’. Or at least not in its entirety. I didn’t avoid them. I simply wasn’t aware of their existence. I was only seven. The closest I had ever come was the oddity of watching Sean Connery wrestle a yard gnome in Darby O’Gill and the Little People. A year would pass before the creature’s face from the drive-in quickie I Was A Teenage Frankenstein––re-colored in putrid greens, bilious yellows and, of course, abattoir reds––would etch itself on my retinas in jolting close-up. And before Mr. Bennie, our neighborhood druggist, in a moment worthy of the younger Lon Chaney’s lycanthropic-transformations, would exchange a pair of quarters for my first issue of Famous Monsters of Filmland. I was a long ways off from becoming the monster-obsessed geek I am today.

My fondness for Mad magazine; the jigglesome curves of Little Annie Fanny; Rocky & Bullwinkle; Three Stooges shorts; The Loves of Dobie Gillis’ Maynard G. Krebs; Slinky coils; pink gobs of Silly Putty; Etch-a-Sketch screens; Pez dispensers; chocolate Devil Dogs; Kool-Aid; McDonald’s 15 cent cheeseburgers; and the wayward offspring of tv’s Ernie Kovacs––Sandy Becker, Chuck McCann and Soupy Sales––over-rode all other concerns in my nascent life. And my love for the Fleischer Brothers’ Popeye cartoons transcended even these. So my mother’s intrusion was a breach bordering on the unforgivable.

Nonetheless, as she joined me on the sofa, I retracted my sulky lip, nestled into a burrow of her pungent underarm, and resigned myself to watching the gloomy procession of ghouls lumbering across our tv screen. My mother, a psychiatric nurse, bore no qualms about inflicting needless trauma on my delicate and impressionable psyche, so she unilaterally decided––Popeye be damned!––I would watch my very first ‘spooky movie’ in all its wretched cinematic glory on that blissful Saturday afternoon. Truthfully, until that day on the sofa, my only real encounter with a ‘spooky movie’ happened after a game of mock domesticity in the dirt lot behind the building my family occupied in the late nineteen fifties.

The building was in a neighborhood just on the outskirts of Yale. It was populated by a community of blacks and Latinos who never really benefited from the monies pumped into New Haven’s urban revitalization programs. As I remember it, it was a place noisy with the constant sounds of doo-woppers in harmonized caterwaul; transistor radios crackling with seriously fonky rhythm and blues; and the mambo of spit-curled Puerto Ricans. Lacquered coifs wrapped in neon-colored doo-rags was the order of the day.

Despite whatever booty Santa stashed in our toy-box Christmas Eve, for me and my friends dirt was still our plaything of choice. It was always filled with surprises: colored glass; animal skulls; Cracker Jack toys; bugs; doll parts; weathered centerfolds of mold-stained white women––the top layer of whole, long-forgotten civilizations. It was versatile, too. You could do anything with dirt from build a house to eat it. If God could make people out of dirt, it was good enough for us.

On the day of my initial brush with spooky films, a pre-pubescent love triangle of Kevin, Sharon and I had just finished a pee-soaked round of our special ‘slum-edition’ of house, in which all of the necessary structures and comestibles were made from dirt. I entered my family’s quarters on the second floor, my legs dusty and streaked with urine, and turned on the Motorola. It was tuned, by chance, to the last tragic moments of King Kong. I gaped at the screen in paralyzed awe; reeling in a vertiginous warp of such mind-bending proportions, I would not have a comparable experience until a blotter of brown-dot surged through my system eleven years later.

A squadron of droning biplanes swarmed the gigantic ape hugging the Empire State. Fusillades of machine-gun bullets fired into his heart. The dying colossus stared at the blood pooled in his palm. He gently laid down the woman grasped in his paw on a ledge of the skyscraper. He swooned. Staggered. Fell. Simultaneously, with a reverberating thud, my eighty-year old babysitter stumbled and died on the upper floor.

Beyond this synchronistic collision between Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion mountain gorilla, and a cowled Mr. Death, I had never seen a ‘spooky movie’ in my life. The movie on that blissful Saturday afternoon was a black and white production from the early 1940s. Charlie Chan’s right-hand man, Birmingham Brown, was in it. Birmingham was played by Mantan Moreland but in this movie his name was Jeff. Mantan made a lot of money jeffin’ in Hollywood. Mantan was famous for his adroit comic timing; bug-eyed double takes; slow burns and the phrase “Feets do yo’ stuff!”

Long before Michael Jackson ‘moonwalked’ through “Billy Jean,” Mantan, a vaudeville veteran of the 1920s, encapsulated the existential plight of the disinherited by mastering the metaphorical social allusion of running at frantic speeds while going absolutely nowhere at all. So it was no mistake he found himself in a production of Waiting for Godot at Lincoln Center in the late nineteen fifties.

Mantan was also a Negro (man tan, get it?). And a lot of other Negroes were in it, too. Dead ones. They all looked and behaved like my clan of alcoholic relatives in New Jersey. I suspect this was the reason why my mother wanted me to watch this movie in the first place. One of the dead Negroes in the movie was played by Song of the South‘s original Uncle Remus, who Zippity-Doo-Dahed his way to an Oscar..

Mantan was also a Negro (man tan, get it?). And a lot of other Negroes were in it, too. Dead ones. They all looked and behaved like my clan of alcoholic relatives in New Jersey. I suspect this was the reason why my mother wanted me to watch this movie in the first place. One of the dead Negroes in the movie was played by Song of the South‘s original Uncle Remus, who Zippity-Doo-Dahed his way to an Oscar..

“Beautiful car.” he says to Mantan, his hair electrified bristles. “I drove car like this for Master.”

“Yeah?” Mantan replied with a dubious side glance.

“When I was alive….”

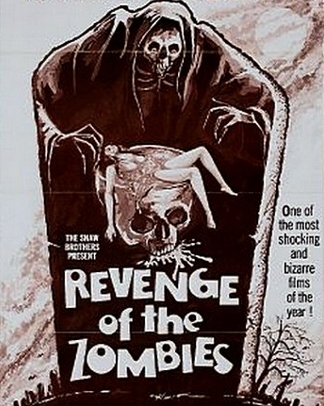

The movie was called Revenge of the Zombies. Its story was set on a former slave plantation in southern Louisiana turned high school science project. John Carradine played the bad guy––Dr. Max Heinrich von Altermann––a hoodoo madman in lab whites. It was Dr. von Altermann who revived my popeyed and stumbling relatives from the dead. With this newly resurrected army of ink-stained Lazaruses, the plan was to conquer the world under the Third Reich’s corporate logo. Unfortunately, as he had never been invited to an outdoor barbecue attended by my pickled kin, and didn’t understand the source materials he was working with, Dr. von Altermann’s plan was doomed to failure from its inception.

The movie also posed vexing questions like: “If the story is framed during W.W. II, the plantation’s original tenants have long since putrefied into some vile-smelling sedimentation, so where did Dr. von Altermann find his army of constipated Negroes? Did he bypass the family plot and cut down what the locals left hanging from the trees?” In addition to Hitler’s new military division––Die Schwarztoten––there was also a wraith-like zombie drifting airily through feathery, moonlit clusters of Spanish moss. And some plantation-era coonfoolery with Mantan and my intoxicated kinfolk but I don’t remember what. Cussing and chicken-thieving most likely.

What I do remember is the piercing voice of a woman who looked and sounded like Aunt Jemima (not in her modern Pearl Bailey incarnation but the handkerchief-headed pancake chef of old) auditioning for the role of Lawrence Talbot in The Wolfman (“Ah’s tire ob’ dis’ hot-ass kitchen!! Can’t ah git off’n dis’ here pancake box an’ makes me de’ big money scarin’ white folks in the monster movies wif’ Frankenstein an’ Dracula?”). The character went by the trite and unimaginative name of Mammy Beulah. However, the actor’s name listed in the credits was ideal for one of Charlie Chan’s yellow-on-high-yellow love interests. Madame Sul-te-wan. Despite her seemingly outrageous name, Madame Sul-Te-Wan (which in truth was Nellie Crawford of Louisville, Kentucky), had the distinction of being a Black American trailblazer. Having worked with such leading lights of American cinema as D.W. Griffith, Lillian Gish and the rest of the monkey people in Birth of Nation and King Kong, she is noted as the first Black American actor to have a genuine movie contract signed by genuine white people with genuine ink that didn’t genuinely disappear!

In Revenge of the Zombies, Madame Sul-Te-Wan stood at the entrance of a fog-shrouded cemetery, and just before a horde of slovenly-dressed Negroes rose from their graves, and shuffled through the gate, she would cry out in eerie blues holler, "Ahhhhhhh-OOOOOOOOO!!!" And the recently arisen would trudge down to the chow wagon for a heaping bowl of cold grits and fly larvae (or whatever it was zombies ate before discovering the nutritional value of the human brain) before beginning another night of undead servitude in the name of the Fuhrer. Arbeit Macht Leiben!

In retrospect, the old woman’s cry had a uniquely haunting quality of its own. It was the movie’s most effective instance of magic. Its echo reverberated in my subconscious for decades thereafter. But, at age seven, I didn’t understand a single emulsified frame in Revenge of the Zombies. I deferred to my mother.

"What’s wrong with them colored people? They drunk? They walk like Uncle Willie."

"No, they’re dead."

I did an owl-eyed double-take. "What you mean dead? Walkin’ don’t come in that package!!"

"They’re special people."

"What you mean special?" I didn’t like the sound of that.

"They’re special because they’re dead people who’ve been brought back to life by voodoo magic."

Doo-doo magic? What this woman talkin’ ’bout? I can take a lump of some stinky old doo-doo, rub it on some dead people and they be up and runnin’ like Remco’s™ Mister Machine? She gone cross-eyed crazy?!!

"If that’s true," I said, remembering the odor that clung to my clothes after I had made pee-pies with the ringworm gang in a nearby empty lot, "why didn’t you let me rub some doo-doo on that lady who dropped dead watchin’ King Kong? The one who used to babysit us? She be sittin’ here right now, smellin’ worse’n Uncle Willie."

"I said Voodoo! Not doo-doo, silly!"

"You talkin’ ’bout bringin’ dead people back to life with som’ voodoo doo-doo an’ you callin’ me silly? I think you need to stop workin’ at that crazy-house an’ turn my tv set back to Popeye!"

Despite the numerous African masks and assorted carvings of various kinds throughout our home; and the marked influence these objects had on my father’s painting and sculpture, my mother didn’t understand, or chose to ignore, the significance of the masks’ spiritual reality or the function this reality served in African art. She had received her training under Dr. Fredrick Wertham in the psychiatric wing of Harlem Hospital (yes, the very same Dr. Wertham reviled by comics aficionados everywhere); but, apparently, was unaware of the objects d’Africaine in Dr. Freud’s Viennese study. Like many modern Blacks, not only in the U.S. but among the educated classes in Haiti and Africa as well, she associated ‘voodoo’ with the culturally embarrassing and infantile practices of half-naked primitives in Jungle Jim’s movie adventures.

Although her mother, my grandmother, was psychically attuned to ancestral spirits, and delivered messages from the long dead who visited her in dreams; and her father, my grandfather, was schooled by his Choctaw grandfather in the medicinal properties of various roots and herbs found in the woods of South Carolina, my mother dismissed it all as nonsense; the product of superstitious bigfoot country Negroes; not the traditional wisdom that aided American blacks through the long nightmare of American slavery. She had chosen to disacknowledge the obvious presence of Voodoo’s vibrant spirituality in her own life and so she certainly couldn’t explain it on the basis of the film we were watching.

However, I can.

In Revenge of the Zombies, ‘voodoo’ isn’t represented as religion or superstitious folk magic. It is rather a ‘mad science’ in the service of white ‘Aryan’ domination. Here, two evils intertwine––the infernal mechanisms of National Socialism and the transported rites of an imagined Africa. Nazism is transformed into a ‘white voodoo’; a ‘voodoo’ defined by corrupt ideology and ‘science’. And, anticipating Papa Doc Duvalier by eleven years, voodoo becomes an instrument of depraved political power. How?

Neither ‘Nazism’ or ‘Voodoo’ are made explicit in the film. They are left unnamed in the narrative space (which is also an invocative ritual-space). The two words ‘Nazism’ and ‘Voodoo’ exist as blanks in a sentence. The sentence speaks only of an inane ‘science’ with southern-gothic trappings. The word ‘voodoo’ is never spoken. The black bodies shaping the narrative emptiness only suggest it. Dr. Von Altermann boasts he is manufacturing automatons for The Fatherland. Which ‘Fatherland’? He doesn’t say.

The viewer is left to fill in the gaps with a stubby pencil.

The blank and unspoken in cinema can be seen in the analogous light of the Sese funeral drum of the matrist Afro-Cuban Abakua´ society. It is a holy drum. It is not played. It is displayed. Significance is imported through silence.

Curiously, as suggested by Article 249 of Haiti’s Criminal Code, the process of ‘zombification’ is achieved not by bringing the dead back to life, but simulating the appearance of death through the administration of various drugs (then providing a partial antidote to rouse the victim to brain damaged semi-consciousness). At the time of Revenge of the Zombies’ release, 1943, the Nazis were, in fact, experimenting with numerous combinations of drugs for the purpose the film implies: turning humans into ‘soulless automatons’. Funny, too, Dr. Von Altermann conducts his experiments on the grounds of a forced labor camp. The film is prescient in this respect.

Now, what’s important to understand, when my mother and I watched Revenge of the Zombies, the movie was broadcast in the very early years of the nineteen sixties. John Kennedy’s courage was the nation’s inspiration. Dr. King had yet to stage his massive March on Washington. School children sang Stephen Foster’s antebellum pop tunes after reciting The Pledge of Allegiance with hand over heart. The sparkling pink behinds of Dick and Jane rubbed against the dusky booty of Little Black Sambo on the library shelf. And blacks were clubbed and firehosed in Alabama’s ‘Magic City’ of Birmingham.

So, as far as television went, there was no such thing as a Sanford and Son. Or that fine figure of American Negritude, Dr. Huxtable, teaching black people how to talk, and make good on the advances of the civil rights movement (because, well, the civil rights movement hadn’t yet made an advance). There was no Fred ‘Rerun’ Berry pop-lockin’ on What’s Happenin’? Or Ted Lange’s bargain basement James Brown on That’s My Mama! No Linc with a blown-out ‘fro on The Mod Squad. Or World Wrestling Federation Stanley Crouch-Imiri Baraka grudge matches!

We didn’t even have a Huggy Bear! We was some iconically deprived Negroes!

At best, we had Harry, Sidney and Sammy. Mostly, we were handed the television equivalent of welfare cheese. Reruns of Amos ‘n Andy; the occasional appearance of Beulah; and endless episodes of those resourceful pickaninnies in The Little Rascals.

I watched any Sepia/Colored/Negro character doled out on the tv set: hankaheads whisking pancake batter in the kitchen; the bizarre, child-like antics of slow-witted yard help; liveried chauffeurs who, at the mere mention of ghosts, sped off in cyclonic clouds of dust tailed by bolts of lightning; snowy-headed retainers who, despite senility and advanced arthritis, could out dance Shirley Temple on their worse days; and, as described earlier, legions of grunting, glassy-eyed grotesques. And do you know why I watched? I wasn’t welcomed in Donna Reed’s house!

Who was Donna Reed? A Honky Bitch who didn’t even have a colored milkman that’s who! You know the milkman I mean. The one you’d see for a hot second. If you were lucky, he lingered long enough to set down the milk bottles and say: "Have a nice duh––" Cut his scene before he could get the ‘ma’am’ out his mouth. That milkman.

The Donna Reed Show was ‘whiteness’ hermetically sealed. Nothing in her world of domesticated blandness represented my own family’s black working-class reality. No drunken uncles. Or psychic grandmothers. No practical parental advice like ‘If you go out an’ getta job shovelin’ elephant shit you can buy your own goddam circus!’

My face was not reflected in her mirror. I could not participate. The disparity between our worlds created mental dissonance. I felt isolated from her world and alienated within my own.

And I know I had these feeling because Timmy lived in a house just like the one I saw on The Donna Reed Show. I once went there to play. And Timmy’s mother served a lunch of baloney and mayonnaise sandwiches on soft white bread with a handful of potato chips.

`Wow! They eat potato chips off of saucers an’ not out the bag! It really is like The Donna Reed Show!´

The next day, I asked Timmy if I could come to his house and play. He said no.

"My mother said you were a nigger and I shouldn’t play with you anymore."

But I didn’t know what a ‘nigger’ was. A three-pronged garden-trowel immediately sprang to mind. ‘Go get the nigger and dig behind the rose bush.’

Why did Timmy’s mother call me a garden tool? Was he saying my mother was a hoe? So, after I popped a couple of blood vessels in Timmy’s nose, I ran home and asked my father.

"What’s a ‘nigger’, Dad?" It was a Beaver Cleaver moment.

His gaze was long and thoughtful. Then he told me to look in a mirror. So I looked in the mirror screwed into the wall above the bathroom sink. Mantan Moreland looked back.

His eyes were pitted cataracts.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

"Son of Kong": Which of the three King Kong films is most relevant to today’s day and age? by Benjamin Strong

"Charlie Chan on Boot DVD" by Kevin Killian

Interview with Marco Williams, director of Banished