2008 New York Film Festival

26.09.08

When a member of the 46th New York Film Festival’s selection committee says that “a festival can only be as good as what’s out there” is there anything left for your Fanzine correspondent to add? I’m a longstanding admirer of Village Voice critic J. Hoberman, one of NYFF 2008’s five programmers, as well as the gracious folks at Lincoln Center who run this annual garden of flickering delights. But Hoberman’s Tuesday preview of the festival, a two-week-plus slate of new movies he helped curate, doesn’t sound like much of an endorsement. Are high expectations to blame?

When a member of the 46th New York Film Festival’s selection committee says that “a festival can only be as good as what’s out there” is there anything left for your Fanzine correspondent to add? I’m a longstanding admirer of Village Voice critic J. Hoberman, one of NYFF 2008’s five programmers, as well as the gracious folks at Lincoln Center who run this annual garden of flickering delights. But Hoberman’s Tuesday preview of the festival, a two-week-plus slate of new movies he helped curate, doesn’t sound like much of an endorsement. Are high expectations to blame?

As usual, the roll call of foreign auteurs is long and stately—Jia Zhang-ke, Olivier Assayas, Lucrecia Martel, Hong Sang-soo, Arnaud Desplechin, Mike Leigh, and others—while in the Yankee column, upcoming releases from critical darlings Darren Aronofsky (Pi, Requiem for a Dream, The Fountain) and Kelly Reichardt (Old Joy) are on tap as well as Changeling, Clint Eastwood’s new period thriller starring Angelina Jolie. And yet, with the exception of Martel’s The Headless Woman (more on it later) your correspondent is feeling underwhelmed.

I had been excited, for example, about Frenchmen Assayas’s Summer Hours and Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale. Yet both turned out to be distastefully tasteful—mere family portraits made watchable by impeccable lead performances (from Charles Berling, and from Mathieu Amalric and Catherine Deneuve, respectively). The scope of these dollhouse films is narrowly bourgeois, which is a particular frustration in the case of Assayas. Although Summer Hours has been called a return to form, I am still one of those people who finds Assayas’s recent low-budget gonzo experiments in globalism—demonlover (2002), Clean (2004) and this spring’s uneven but white hot Boarding Gate—to be his strongest work to date.

I had been excited, for example, about Frenchmen Assayas’s Summer Hours and Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale. Yet both turned out to be distastefully tasteful—mere family portraits made watchable by impeccable lead performances (from Charles Berling, and from Mathieu Amalric and Catherine Deneuve, respectively). The scope of these dollhouse films is narrowly bourgeois, which is a particular frustration in the case of Assayas. Although Summer Hours has been called a return to form, I am still one of those people who finds Assayas’s recent low-budget gonzo experiments in globalism—demonlover (2002), Clean (2004) and this spring’s uneven but white hot Boarding Gate—to be his strongest work to date.

Like Assayas, Jia Zhang-ke is a victim of his own precedent. Still Life, Jia’s look at the luckless souls displaced by the Chinese government’s massive Yangtze River development, opened in American theaters in January, while Useless, his stream-of-consciousness documentary about the Chinese garment industry, was a highlight of last year’s NYFF. Jia has made a name for himself as an existential chronicler of the impoverished working class, and heretofore he has flown under Beijing’s radar by shooting independent productions that have no scripts and which classify, on technicalities, as documentaries. This has allowed him to circumvent China’s otherwise strict censorship laws. “First, you have to hand over your script. Then they go through your rushes, during the shooting,” Jia told a British newspaper in 2002. “I think if a film can pass such censorship, there can’t be true characters in it.”

The problem then with 24 City, Jia’s contribution to this year’s festival (along with a 19-minute short entitled Cry Me a River) is that it is the first movie he has made that was subject to official approval. An oral history of a Mao-era aerospace plant called Factory 420 that is in the process of being converted into luxury condos, 24 City mixes interviews of former workers with monologues by professional actors, including the director’s regular muse, Zhao Tao, and an unrecognizable Joan Chen (a.k.a Josie Packard). Jia’s cup may still runneth over with skepticism about the free market, but all the same 24 City exudes a discomforting nostalgia for Communist rule. The stories Jia’s characters tell are undeniably engrossing, but are these people, as the director himself put it, “true”?

Mention must also be made of Afterschool. It was the only NYFF entry I actually despised and was also the only movie, of the nine press and industry screenings I have so far attended, to receive actual applause afterwards. Pitched as an exposé of sex, drugs, and violence among Manhattan teens marooned at a Connecticut prep school, Antonio Campos’s debut has going for it the affectless performances of its amateur cast combined with some inventive lensing from cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes. But Campos’s sophomoric observations about mass media and his woe-is-rich-kids vibe are off-putting. Anyone looking for a text that blames adolescent immorality on the hypocrisy of adults is better off sticking with Catcher in the Rye.

Mention must also be made of Afterschool. It was the only NYFF entry I actually despised and was also the only movie, of the nine press and industry screenings I have so far attended, to receive actual applause afterwards. Pitched as an exposé of sex, drugs, and violence among Manhattan teens marooned at a Connecticut prep school, Antonio Campos’s debut has going for it the affectless performances of its amateur cast combined with some inventive lensing from cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes. But Campos’s sophomoric observations about mass media and his woe-is-rich-kids vibe are off-putting. Anyone looking for a text that blames adolescent immorality on the hypocrisy of adults is better off sticking with Catcher in the Rye.

Anomie is also the subject of A Headless Woman (the original title, la mujer sin cabeza, is an Argentinian expression for a woman with no sense), though in contrast with Campos, director Lucrecia Martel envisions a world where everyone is culpable, if not accountable. In Woman’s first scene titular dentist Verónica (Maria Onetto), distracted by her cellphone while driving, runs over something or someone. She flees the scene, then tries to forget the incident ever happened, only to learn a week later that she may have killed a child. This prompts her family and friends to circle their wagons, methodically erasing any evidence that she was ever on that road. While Verónica is the one who commits the crime, her loved ones are the engineers of a cover-up that renders her imprisoned with her own guilt. Atmospheric, mysterious, and formally ethereal, A Headless Woman is a unnerving study of the price a society pays for silence.

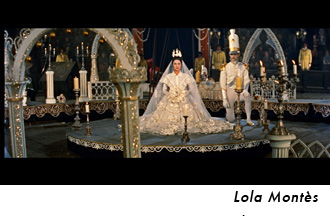

To say that NYFF 2008 is a total letdown would be overstating things. For one thing, the movie I have most looked forward to, Steven Soderbergh’s five-hour Benicio Del Toro-helmed biopic Che, hasn’t even previewed yet for critics (it will screen for the public on October 7). Moreover, the sidebars, as always, rule. On the avant-garde end alone, there’s theorist Guy Debord’s 1978 oddity, In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni, as well as James Benning’s RR, a two-hour feast of watching trains go by. And then restoration-wise, on October 4, the landmark Zeigfeld Theater will host NYFF’s screening of a new version of Max Ophul’s last film, the long chopped-up masterpiece, Lola Montès (1955).

To say that NYFF 2008 is a total letdown would be overstating things. For one thing, the movie I have most looked forward to, Steven Soderbergh’s five-hour Benicio Del Toro-helmed biopic Che, hasn’t even previewed yet for critics (it will screen for the public on October 7). Moreover, the sidebars, as always, rule. On the avant-garde end alone, there’s theorist Guy Debord’s 1978 oddity, In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni, as well as James Benning’s RR, a two-hour feast of watching trains go by. And then restoration-wise, on October 4, the landmark Zeigfeld Theater will host NYFF’s screening of a new version of Max Ophul’s last film, the long chopped-up masterpiece, Lola Montès (1955).

The only picture Ophuls ever shot in color, Lola Montès is also in CinemaScope. Lusty, overcooked, and fashionably jaded, it’s the story of a nineteenth-century femme fatale and the men she beds (who include a Prussian King, Franz Liszt, and a young Peter Ustinov) before ending up, in her later years, as a circus freak. Ophuls was purportedly interested in everyone but the title character (“that woman doesn’t interest me”), but the main attraction here is his gliding camera, which somehow manages to snake through complex interiors without ever seeming intrusive.

Eastwood’s Changeling is the festival’s nominal centerpiece selection, but it is Lola Montès that is the heart of this year’s program. It is therefore worth remembering that Ophuls’s swan song was a flop upon its initial release. NYFF 2008 may only be as good as what’s out there, but for better or for worse what’s out there isn’t going to look the same to us fifty-three years from now.

*cover image from Changeling directed by Clint Eastwood