Jaws Revisited

15.09.08

With the advent of DVDs, the idea of a “final cut” is a thing of movie past. Now when thinking and writing about a film, one must look beyond the given frame and take into account a much larger cinematic space that includes deleted scenes, outtakes, interviews, featurettes, production photos, storyboards, and commentaries. In other words, what’s “in” and “not” in the film, what is or could have been the story. As a cinematic tribute to yet another summer nearing its apex, Jaws, the now tri-decade pop-culture phenomenon, was recently screened on TV as part of a four-day marathon on channel My9. After viewing Jaws on TV in New York City, I also watched the wide-screen 30th Anniversary Edition on DVD. Disc One contains thirteen minutes of deleted scenes and outtakes as well as an on-location featurette filmed on Martha’s Vineyard for British TV on May 6, 1974.

With the advent of DVDs, the idea of a “final cut” is a thing of movie past. Now when thinking and writing about a film, one must look beyond the given frame and take into account a much larger cinematic space that includes deleted scenes, outtakes, interviews, featurettes, production photos, storyboards, and commentaries. In other words, what’s “in” and “not” in the film, what is or could have been the story. As a cinematic tribute to yet another summer nearing its apex, Jaws, the now tri-decade pop-culture phenomenon, was recently screened on TV as part of a four-day marathon on channel My9. After viewing Jaws on TV in New York City, I also watched the wide-screen 30th Anniversary Edition on DVD. Disc One contains thirteen minutes of deleted scenes and outtakes as well as an on-location featurette filmed on Martha’s Vineyard for British TV on May 6, 1974.

In light of these deleted scenes and outtakes, and given Jaws’ infamous production history widely documented in a variety of forms, I’ve decided to revisit Jaws to reflect on the movie it could have been, and despite the now-included cuts, in an abstract way, still is. Even if scenes go unused and end up on the cutting room floor, they were still written, acted, and shot, and therefore occupy some spectral, or analogous, presence in the cinematic narrative, resulting in a film double or cinematic imaginary that deserves consideration. As a reprocessing of scenes, or, as the film critic Nigel Andrews put it in his book on Jaws, “scenes collected from the artist’s bigger canvas,” DVD extra-features result in a thematic and informational reassembly. Things are cropped, cut, panned, or reformulated to accommodate certain cultural or technological criteria endemic of any made-for, or made-to-fit, context. The pan-and-scan process, “whereby a widescreen film’s images are cropped, lopped, and otherwise mutilated to fit the full frame of the squarer television screen,” Andrews writes, can be seen as the reverse of the DVD auxiliary, which seeks to supplement the viewer with more, rather than less-than the original.

Up until a few years ago, when I experienced my first theater screening of Jaws in London (in conjunction with an ICA panel hosted by the film critic Antonia Quirke, who wrote a BFI Classic on Jaws, and the release of the wide-screen DVD 30th Anniversary edition of the movie), I had only ever seen Jaws on full-screen TV. Whereas the full-screen telefilm versions of movies conform to whatever-fits-the-frame, it can be argued that the widescreen DVD, in tandem with the extra-feature, is everything-that-didn’t-fit-the-frame-before or everything-we-can-now-cram-into-it-and-more. Further, while full-screen TV movie adaptations are guilty of artistic depletion and a “mono-dimensionality…[in order to] prioritize Primal Story Information and to let background, ambience and subsidiary visual detail, all the things that enrich a large-screen film, go hang,”(Andrews) the extra-feature, with its mythopoeic emphasis on production (behind-the-scenes and deleted footage), makes the frame frameless and infinitesimal in its variation. Panning-and-scanning, writes Andrews, “is what the audience must know to follow the plot or get its point…The effect of the pan-and-scan process is to reduce a large-screen movie to this elementary information feed.” That is, in pan-and-scan format, the movie Jaws gets reduced to the most literal definition of the shark (an eating machine chewing at the scenery). With the special feature additions, however, the movie is not just restored to its intended holistic glory, but to a life that extends far beyond the given (wide) screen and connects to not just cinema as a whole, but to the reception of and relationship we have to the stories behind cinematic images. As a movie that has had a powerful and reverberant cultural life off-screen, the same life that created the screen’s fictional response to begin with, Jaws’ context continues to be feverishly nourished and added to.

In an interview with Nigel Andrews, Steven Spielberg comments on the subject of cinematic alteration: “I’m sad seeing my movies on television or video because I don’t want my work altered and my work is altered the minute a widescreen movie, meaning a film I shot in Panavision, is shown on the small screen because you’re only seeing half my movie.” What is interesting about Spielberg’s, and by extension Andrew’s, comment, is that it only acknowledges modification as an exclusion or cut, while extra-footage (earlier cuts), which equally warp, are not perceived as a hypothetical re-rendering and stretching of the official border of a film text. Contrary to what Spielberg thinks, whether it’s taken out or put back in, new information modifies what we see and how we see it. “Happily, there is a small light at the tunnel’s end,” concludes Andrews. “…More and more feature films released on video today, including Jaws, are now appearing in wide-screen.” But more important than simply having extra, is the ability to understand what the extra means, how and where it fits, and what it does to the already existing and known.

In an interview with Nigel Andrews, Steven Spielberg comments on the subject of cinematic alteration: “I’m sad seeing my movies on television or video because I don’t want my work altered and my work is altered the minute a widescreen movie, meaning a film I shot in Panavision, is shown on the small screen because you’re only seeing half my movie.” What is interesting about Spielberg’s, and by extension Andrew’s, comment, is that it only acknowledges modification as an exclusion or cut, while extra-footage (earlier cuts), which equally warp, are not perceived as a hypothetical re-rendering and stretching of the official border of a film text. Contrary to what Spielberg thinks, whether it’s taken out or put back in, new information modifies what we see and how we see it. “Happily, there is a small light at the tunnel’s end,” concludes Andrews. “…More and more feature films released on video today, including Jaws, are now appearing in wide-screen.” But more important than simply having extra, is the ability to understand what the extra means, how and where it fits, and what it does to the already existing and known.

So what role do these cinematic additions play? Like diary entries or notes, deleted scenes and outtakes unveil connotative narrative and meaning. Further, threaded into the fabric of the “final cut,” one begins to see things that weren’t originally there. In The Shining, Scatman Crothers tries to explain Danny’s telepathy to him in a way that he can understand. “When something happens,” he tells him, “it can leave a trace of itself behind.” While watching the documentary Making the Shining last year I was struck by how the crew played music while shooting the movie’s denouement in which Danny runs through the Overlook’s outdoor snow-filled maze. As a child, and an untrained actor, Danny, played by Danny Lloyd, having no emotional context for the scene, needed some kind of representation of the fear he had to fake. Similar to the Jaws theme, where signature music is used to characterize or anticipate the shark, creating a context for horror even when it isn’t being explicitly shown, music, which is added to a film in post-production, is used in The Shining for the actual making of the movie, and in this case generates a scene or performance instead of the other way around. According to Stanley Kubrick, the film’s director, in an effort to “shield” the child actor from any knowledge of violence, Lloyd had no idea what he was shooting and didn’t even know he was in a horror movie the entire time he was on-set. The idea of making a film about fear without a context of fear is interesting. In the case of Jaws, seeing the behind-the-scenes takes the horror out of the horror, or the “real” out of the scene, reducing it to just plain reel. In Jaws, this is never more apparent than when the shark is shown unedited and un-scored, exposing it as nothing more than a poorly operated piece of clunky machinery.

Sometimes the reverse is true, or the horror of on-screen interfaces with the horror of off-screen. I was just as nervous, for example, while watching the documentary footage of The Shining as I was watching the actual movie. The psychosexual abuse and tension that Jack Nicholson and Stanley Kubrick inflict on Shelley Duvall, the female lead, is equally punishing. In some ways, Duvall the actress is treated just as badly as Wendy the fictional character, and one comes to realize that not only is the performance onscreen informed by Duvall’s experience “off”-camera—as both women are pushed to the edge—but, one wants to ask, what exactly is diegetic reality?

With Jaws, the picture Steven Spielberg not only made, but intended to make, becomes transparent through the recovery of erasure. Editing becomes not just a formal strategy of composition, but also a symbolic removal, or remolding, of one’s footprints in the sand, or, in the case of The Shining, the snow. As reinstated cuts, special features are a way of pretending what was on film never really was. As a disastrously famous production, even on-set script writer/doctor and author of the just as iconic Jaws Log, Carl Gottlieb, has concurred, Jaws also ended up being a movie about the making of a movie.

With Jaws, the picture Steven Spielberg not only made, but intended to make, becomes transparent through the recovery of erasure. Editing becomes not just a formal strategy of composition, but also a symbolic removal, or remolding, of one’s footprints in the sand, or, in the case of The Shining, the snow. As reinstated cuts, special features are a way of pretending what was on film never really was. As a disastrously famous production, even on-set script writer/doctor and author of the just as iconic Jaws Log, Carl Gottlieb, has concurred, Jaws also ended up being a movie about the making of a movie.

Rape

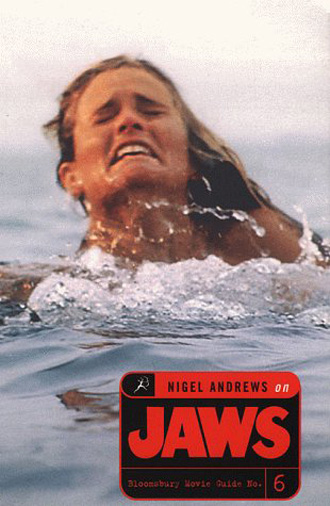

The water looks beautiful. It’s real, and so is that moon and so are those stars. You want to go in. You never doubt Jaws’ treatment of landscape—“a love poem to water—” (writes Antonia Quirke) because it breathes. Chrissie, the lone swimmer, is the movie’s exemplary female victim. Her death, which has been described as rape, touches upon a number of sexual scenarios, most notably, the sub-category date rape. Her death is literally a “date” gone awry. Though I’ve written about Chrissie before, I see new things this time around. The way she sheds her clothes, piece by piece, along the jagged “teeth” of the dune fence, like she’ll never need them again before running into the water. The way Brody collects them like crumbs that lead him to the shark the next morning. The way Chrissie sits in isolation at the beach, removed from the rest of the group. The way Tom Cassidy mirrors the predatory gaze and sexual assault the shark inflicts upon Chrissie in the water. Not only does Chrissie sit alone at the bonfire, she swims alone too. Her attack has been read as Cassidy’s displaced rage over Chrissie “running out” on him, as Chief Brody puts it the next morning when she goes missing. In one of the earlier drafts of the script, Chrissie’s last name is Worthington, but when asked, Cassidy says, “Worthingsly,” which sounds a lot like “worthless.” I also notice that the movie goes out of its way to spare Cassidy’s life—the preppy upper-class boy Chrissie wants to have sex with—while greedily taking hers. The film makes Cassidy too drunk to swim or have sex, and saves him by letting him pass out on shore while Chrissie swims brazenly into the “dark” ocean like a nubile siren (or, to use the date rape term, “tease”). As a woman who clearly loves to swim alone, Chrissie is punished for basking in her own eroticism. Her pleasure in the water is not contingent upon whether Cassidy joins her. And while her death is standard punishment doled out to girls who have, or in her case want to have sex, had Chrissie and Cassidy been attacked in the water together, they would still have suffered the death penalty that comes with being sexual in the horror genre. In the storyboard drawings, Chrissie and Cassidy fuck under a big, low moon that hangs over what looks more like a cityscape then a seascape. After which, Chrissie, seemingly possessed by the lunar light, walks solo into the water for a sacrificial swim. In the storyboard drawings of the shark attack, Chrissie’s breasts are bared, in the film version, the water sheathes her from top to bottom as the lower half (the sex organs) of her body gets ripped (fucked) apart.

Then there are the words. When the “nice” boy Cassidy passes out on shore, leaving Chrissie to metaphorically walk home alone, she runs into the bad boy. Think of Jodie Foster in The Accused showing up at the wrong bar. The shark is a bad fish, the immoral sailor, like the one who tries to rape Marnie’s mother in Marnie. In a bizarrely revealing assessment of cinematic value and coincidence, a time capsule containing five items was buried in 1989 on Universal’s 25th Anniversary. It was to be opened on Universal’s fiftieth. It contained: “a swatch of King Kong’s fur, the hat worn by Ernest Borgnine in the 1964 film McHale’s Navy, a seismogram from Earthquake, a tooth from the shark in Jaws, and Sean Connery’s bow-tie from Marnie.”

In addtion to screaming for help during her brutal attack, Chrissie also exclaims, “Oh God, it hurts. It hurts,” which are more than just straightforward exclamations of physical pain and torment. They are also allusions to sexual violation. Chrissie’s guttural cries are met with soft whispers from Cassidy, who is passed out on shore wearing nothing but his underwear by the end. “I’m coming, I’m coming,” he moans, leaving “his id to ventriloquize the ravishing passion of the shark.” (Andrews) In his drunken stupor, Cassidy has something between a wet dream and the vicarious pleasure of hearing Chrissie get fucked (punished) by something else. Chrissie’s cries for help also recall pubescent Regan MacNeil in the earlier horror flick The Exorcist. “It burns, it burns,” Regan tells her mother when the Devil has his way with her. “Burning” becomes synonymous with the pain of sexual penetration. Like The Entity, in which a malevolent male spirit repeatedly rapes Barbara Hershey, something neither the victim nor viewers can see rapes Chrissie. According to Chrissie portrayer Susan Backlinie, a fearless underwater stuntwoman, the scene was shot and re-shot thirty or forty times. And according to the documentary The Making of Jaws, Backlinie reveals that Spielberg himself was behind some of the key stunts she performs. Namely, the pulling of the severe cable harness Backlinie was strapped into in the water, and tugged at from opposite sides of the beach, as well as the sound of her drowning, which was looped in during post-production and achieved by positioning Backlinie, head upturned, in front of a microphone, while water from above was poured down her throat. In his essay, “Jaws, Ideology, and Film Theory,” British film scholar Stephen Heath argues that Chrissie’s murder is a symbolic act of female genocide. Like Shelley Duvall in The Shining, Backlinie goes through off-screen hell to enact Chrissie’s viscerally terrifying death. In my book Beauty Talk & Monsters I write about the time when, during the filming of Close Encounters in India, the Bombay press asked the movie’s producer, Julia Phillips, how Steven Spielberg “got the girl in the beginning of Jaws to go this way and that way so violently in the water?” She writes—but didn’t say—in her memoir You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again, “fearless stuntwoman, ten men, ten harnesses, pushpullpushpull, lacerations and bruises for years to come, don’t ask.” We know from interviews about the making of The Exorcist, as well as Peter Biskand’s tell-all about the movie industry of the 1970s, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, that Ellen Burstyn suffered her own harness horror in the hands of director William Friedkin.

In addtion to screaming for help during her brutal attack, Chrissie also exclaims, “Oh God, it hurts. It hurts,” which are more than just straightforward exclamations of physical pain and torment. They are also allusions to sexual violation. Chrissie’s guttural cries are met with soft whispers from Cassidy, who is passed out on shore wearing nothing but his underwear by the end. “I’m coming, I’m coming,” he moans, leaving “his id to ventriloquize the ravishing passion of the shark.” (Andrews) In his drunken stupor, Cassidy has something between a wet dream and the vicarious pleasure of hearing Chrissie get fucked (punished) by something else. Chrissie’s cries for help also recall pubescent Regan MacNeil in the earlier horror flick The Exorcist. “It burns, it burns,” Regan tells her mother when the Devil has his way with her. “Burning” becomes synonymous with the pain of sexual penetration. Like The Entity, in which a malevolent male spirit repeatedly rapes Barbara Hershey, something neither the victim nor viewers can see rapes Chrissie. According to Chrissie portrayer Susan Backlinie, a fearless underwater stuntwoman, the scene was shot and re-shot thirty or forty times. And according to the documentary The Making of Jaws, Backlinie reveals that Spielberg himself was behind some of the key stunts she performs. Namely, the pulling of the severe cable harness Backlinie was strapped into in the water, and tugged at from opposite sides of the beach, as well as the sound of her drowning, which was looped in during post-production and achieved by positioning Backlinie, head upturned, in front of a microphone, while water from above was poured down her throat. In his essay, “Jaws, Ideology, and Film Theory,” British film scholar Stephen Heath argues that Chrissie’s murder is a symbolic act of female genocide. Like Shelley Duvall in The Shining, Backlinie goes through off-screen hell to enact Chrissie’s viscerally terrifying death. In my book Beauty Talk & Monsters I write about the time when, during the filming of Close Encounters in India, the Bombay press asked the movie’s producer, Julia Phillips, how Steven Spielberg “got the girl in the beginning of Jaws to go this way and that way so violently in the water?” She writes—but didn’t say—in her memoir You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again, “fearless stuntwoman, ten men, ten harnesses, pushpullpushpull, lacerations and bruises for years to come, don’t ask.” We know from interviews about the making of The Exorcist, as well as Peter Biskand’s tell-all about the movie industry of the 1970s, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, that Ellen Burstyn suffered her own harness horror in the hands of director William Friedkin.

Interestingly, Jaws’ other major shark victim is the Kintner boy, Alex, the son of a single mother (most likely a widow) who in the storyboard drawings is young, fit, and bikini-clad, more a beach babe then the austere (sexless) older woman she becomes in the movie. It is Mrs. Kintner who publicly slaps, and therefore indicts, the already-emasculated Chief Brody. And it is her slap that induces Brody’s shark-hunt odyssey in an effort to reclaim his manhood. Brody’s fear of the water doesn’t need elaboration. His phobia is allegorical and part of the emotional economy of patriarchy: fear of the feminine, or the unknown primordial “deep.”

In the deleted scene that follows, Brody and Cassidy talk while looking for Chrissie on the beach. In this version, Cassidy is testy, his ego visibly bruised by Chrissie’s “disappearance” the night before. When Brody accuses Chrissie of “running out on” Cassidy, a line that exists in the script, theatrical version of the film and in the deleted scene, Cassidy’s reaction is played much more aggressively and defensively, and therefore fits the profile of a rape case. Could he have done it? Did she run out on him? The scene is edited around behavioral and gestural complicity. His body, and the signals it sends, will determine his guilt. But Spielberg decides to take this out. It isn’t necessary. He isn’t guilty, the shark is, so why even toy with blame? Men aren’t the problem in this story. Tom Cassidy is merely in the film to lead us to the shark and he has. When grilled by Chief Brody, Cassidy bites back, firing, “Look, I reported it, didn’t I?” Killers don’t report murders. In the deleted scene, when Cassidy plucks (we don’t see him do it) a single stake from the sprawling dune fence that resembles a row of teeth or the vertebrae “of some primeval monster,” (Andrews) and then snaps and throws the stick, it’s much more forceful than the way he breaks the stake in the released version. In the deleted version, the act actually interrupts the flow of dialogue with Brody—who notices it—and more importantly, Cassidy’s credibility. It makes him capable of violent retaliation. In the take that was used, Cassidy breaks the stick nervously because he’s anxious and needs something to do with his dread. Breaking the stick is presented as more of a nervous tic and goes unregistered by Brody, who keeps talking. In the deleted scene, however, Cassidy breaks the stick as a physical representation of his anger, to accent it, and then follows with, “Look, I reported it, didn’t I?” His voice higher and more petulant in this take. In another deleted scene, Chrissie’s body isn’t found by the young Deputy “Lenny” Hendricks, but by Brody, who espies it over a sand dune and then forces Cassidy to look for himself, as if charging him with guilt. Cassidy, who is essentially ambivalent about Chrissie’s death in the released film version, is nearly hysterical in the deleted scene.

In the deleted scene that follows, Brody and Cassidy talk while looking for Chrissie on the beach. In this version, Cassidy is testy, his ego visibly bruised by Chrissie’s “disappearance” the night before. When Brody accuses Chrissie of “running out on” Cassidy, a line that exists in the script, theatrical version of the film and in the deleted scene, Cassidy’s reaction is played much more aggressively and defensively, and therefore fits the profile of a rape case. Could he have done it? Did she run out on him? The scene is edited around behavioral and gestural complicity. His body, and the signals it sends, will determine his guilt. But Spielberg decides to take this out. It isn’t necessary. He isn’t guilty, the shark is, so why even toy with blame? Men aren’t the problem in this story. Tom Cassidy is merely in the film to lead us to the shark and he has. When grilled by Chief Brody, Cassidy bites back, firing, “Look, I reported it, didn’t I?” Killers don’t report murders. In the deleted scene, when Cassidy plucks (we don’t see him do it) a single stake from the sprawling dune fence that resembles a row of teeth or the vertebrae “of some primeval monster,” (Andrews) and then snaps and throws the stick, it’s much more forceful than the way he breaks the stake in the released version. In the deleted version, the act actually interrupts the flow of dialogue with Brody—who notices it—and more importantly, Cassidy’s credibility. It makes him capable of violent retaliation. In the take that was used, Cassidy breaks the stick nervously because he’s anxious and needs something to do with his dread. Breaking the stick is presented as more of a nervous tic and goes unregistered by Brody, who keeps talking. In the deleted scene, however, Cassidy breaks the stick as a physical representation of his anger, to accent it, and then follows with, “Look, I reported it, didn’t I?” His voice higher and more petulant in this take. In another deleted scene, Chrissie’s body isn’t found by the young Deputy “Lenny” Hendricks, but by Brody, who espies it over a sand dune and then forces Cassidy to look for himself, as if charging him with guilt. Cassidy, who is essentially ambivalent about Chrissie’s death in the released film version, is nearly hysterical in the deleted scene.

Hooper (“Think how off-putting this character could have been” -Nigel Andrews)

John Voight, Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges, even Cabaret’s Joel Grey could have played Matt Hooper. But they all said no. Universal Studios’ choice was Jan-Michael Vincent, who a few years later starred in another water movie, John Milius’ elegy to surfing, Big Wednesday. Milius has been credited with writing a version of Quint’s Indianapolis speech. Even Dreyfuss said no to playing Hooper, stating he would rather watch Jaws then make it. But then he saw himself on-screen in the 1974 Canadian film The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and was so mortified by the quality of his acting and the shock of seeing his face fifteen feet high, that he panicked over his prospects, and begged Spielberg for the part. In The Making of Jaws, Spielberg states that he wanted to audition the entire male cast of Peter Bodanovich’s The Last Picture Show—one of his favorite movies—for Jaws’ male leads.

In a deleted scene, shark expert Hopper and Chief Brody crawl under a landing pier together, flashlights in hand, to get to the Tiger shark Hooper plans to autopsy. The movie cuts from Hooper and Brody talking sharks at Brody’s house, to gutting one for evidence. In the released take, the shark remains primary; it’s the thing that bonds the two men, and the action continues along a straight line. In the deleted scene, however, the line takes a detour around the insides of Hopper. The effect is jarring. Hooper is caught not thinking about the shark, but rather bragging about the details of his erotic encounters, in particular obscene phone calls from ex-lovers, to an always-preoccupied Brody. In the unused scene, Hooper is callow, not just in age, but in soul. Driven by basic instincts, like the shark, he comes across as a man mentally off-duty and therefore strays from the A-Z story. This is the Hooper that has an affair with Ellen Brody, and since the producers David Brown and Robert Zanuck, as well as Spielberg, who, as the director, identifies with the character of Hooper, banned the affair from the movie version of Jaws, this small scene—the residual connective tissue of the affair—has to go to. “One of the key decisions we made early on,” informs Zanuck, “was to take the sex scenes out of the story of Jaws.” As Peter Biskand put it in his essay on the blockbuster, “The Last Crusade,” “Mark Hamill was not about to disrupt Star Wars by lisping (like Marlon Brando in Missouri Breaks), wearing a dress, and upstaging the robots.” If left in, Hopper would no longer be just an emblem of science and modernity, there to move the action along with the information/knowledge he possesses—one of the three tools employed against the marauding shark—but a man with extra-diegetic features and connotations. And since Jaws is a film in which the three models of masculinity hinge upon and reflect off each other like glass, the triptych they form must be palliated on screen in a delicate equilibrium of characterization. This triptych is introduced early on in the opening credits as a theme when the names Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Richard Dreyfus appear in the shape of a triangle (mirroring, as Nigel Andrews has pointed out, “the classic triangular figuration of the ego, superego, and id. The pointy-faced shark is also in the shape of the pyramidal ego structure”), like the now iconic shark maw rising out of the “deep” towards the surface of the water. If this version of Hooper had remained, the scales would tip too far to one side, and therefore something about Brody would have to shift. What’s more, Hooper’s sex life, like the dark passageway he’s shown walking through with Brody, moves his character beyond the given frame and into something inscrutable. Rather than shed light, it casts a shadow where shadows are not wanted.

In a deleted scene, shark expert Hopper and Chief Brody crawl under a landing pier together, flashlights in hand, to get to the Tiger shark Hooper plans to autopsy. The movie cuts from Hooper and Brody talking sharks at Brody’s house, to gutting one for evidence. In the released take, the shark remains primary; it’s the thing that bonds the two men, and the action continues along a straight line. In the deleted scene, however, the line takes a detour around the insides of Hopper. The effect is jarring. Hooper is caught not thinking about the shark, but rather bragging about the details of his erotic encounters, in particular obscene phone calls from ex-lovers, to an always-preoccupied Brody. In the unused scene, Hooper is callow, not just in age, but in soul. Driven by basic instincts, like the shark, he comes across as a man mentally off-duty and therefore strays from the A-Z story. This is the Hooper that has an affair with Ellen Brody, and since the producers David Brown and Robert Zanuck, as well as Spielberg, who, as the director, identifies with the character of Hooper, banned the affair from the movie version of Jaws, this small scene—the residual connective tissue of the affair—has to go to. “One of the key decisions we made early on,” informs Zanuck, “was to take the sex scenes out of the story of Jaws.” As Peter Biskand put it in his essay on the blockbuster, “The Last Crusade,” “Mark Hamill was not about to disrupt Star Wars by lisping (like Marlon Brando in Missouri Breaks), wearing a dress, and upstaging the robots.” If left in, Hopper would no longer be just an emblem of science and modernity, there to move the action along with the information/knowledge he possesses—one of the three tools employed against the marauding shark—but a man with extra-diegetic features and connotations. And since Jaws is a film in which the three models of masculinity hinge upon and reflect off each other like glass, the triptych they form must be palliated on screen in a delicate equilibrium of characterization. This triptych is introduced early on in the opening credits as a theme when the names Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Richard Dreyfus appear in the shape of a triangle (mirroring, as Nigel Andrews has pointed out, “the classic triangular figuration of the ego, superego, and id. The pointy-faced shark is also in the shape of the pyramidal ego structure”), like the now iconic shark maw rising out of the “deep” towards the surface of the water. If this version of Hooper had remained, the scales would tip too far to one side, and therefore something about Brody would have to shift. What’s more, Hooper’s sex life, like the dark passageway he’s shown walking through with Brody, moves his character beyond the given frame and into something inscrutable. Rather than shed light, it casts a shadow where shadows are not wanted.

As a movie, Jaws is intensely diegetic. It doesn’t want its audience to stray from the world of the fiction for even a second. And, unlike the entirely banal Jaws 2, Jaws is a narrative of archetypal economy. This is where Spielberg’s penchant for fantasy and escapism (total immersion in the film world) borders on an imperial takeover of the cinematic imagination. While George Lucas and Steven Spielberg undermine authority in their films, notes Biskand, they do it in order to delve deeper into fantasy. In their films, the disaffected era of the Vietnam generation was repossessed into the cinematic fold, and social reality was retreated from altogether. In the deleted scene, Matt Hooper’s character is extended beyond its utilitarian and diegetic purposes. If left in, the film would start to take on the quality of a paranoid 1970s conspiracy thriller (note the mayoral corruption in Jaws hinting at Watergate) in the vein of All The Presidents Men, The Parallax View, The Conversation, or Serpico. But, as Antonia Quirke rightly points out in her BFI Classic on Jaws, the film doesn’t go in that direction because Spielberg is trying to “brin[g] everything down out of the neurotic 1970s into a Boys’ Own adventure story.” While the films of The New Hollywood are products of the rebellion movements of the 1960s, and therefore attempted to reformulate genre by blurring the line between diegetic and non-diegetic (and in the process, calling attention to the construction of film, as well as opening the movie narrative to the socio-historic realities of the non-diegetic world), Spielberg, along with George Lucas, restored the hermeticism of the cinematic frame in the same way that thematically his movies attempt to reconstitute the nuclear family. (Tellingly, in The Making of Jaws Spielberg states that one of the main reasons he chose Martha’s Vineyard as the film’s location was because he could easily obscure terra firma from view in the third act, making both the men on the Orca and the viewers in the theater feel stranded at sea.)

As a movie, Jaws is intensely diegetic. It doesn’t want its audience to stray from the world of the fiction for even a second. And, unlike the entirely banal Jaws 2, Jaws is a narrative of archetypal economy. This is where Spielberg’s penchant for fantasy and escapism (total immersion in the film world) borders on an imperial takeover of the cinematic imagination. While George Lucas and Steven Spielberg undermine authority in their films, notes Biskand, they do it in order to delve deeper into fantasy. In their films, the disaffected era of the Vietnam generation was repossessed into the cinematic fold, and social reality was retreated from altogether. In the deleted scene, Matt Hooper’s character is extended beyond its utilitarian and diegetic purposes. If left in, the film would start to take on the quality of a paranoid 1970s conspiracy thriller (note the mayoral corruption in Jaws hinting at Watergate) in the vein of All The Presidents Men, The Parallax View, The Conversation, or Serpico. But, as Antonia Quirke rightly points out in her BFI Classic on Jaws, the film doesn’t go in that direction because Spielberg is trying to “brin[g] everything down out of the neurotic 1970s into a Boys’ Own adventure story.” While the films of The New Hollywood are products of the rebellion movements of the 1960s, and therefore attempted to reformulate genre by blurring the line between diegetic and non-diegetic (and in the process, calling attention to the construction of film, as well as opening the movie narrative to the socio-historic realities of the non-diegetic world), Spielberg, along with George Lucas, restored the hermeticism of the cinematic frame in the same way that thematically his movies attempt to reconstitute the nuclear family. (Tellingly, in The Making of Jaws Spielberg states that one of the main reasons he chose Martha’s Vineyard as the film’s location was because he could easily obscure terra firma from view in the third act, making both the men on the Orca and the viewers in the theater feel stranded at sea.)

Outtakes

The domestic outtakes and deleted scenes of Roy Scheider and Lorraine Gary outwardly display a stifled marriage as well as Chief Brody’s professional and personal dissatisfaction, an unhappiness that the final version of Jaws only skirts around. “To dispense with dialogue in order to establish character,” writes Antonia Quirke, “to find both narrative and poem in silence, marks the young Spielberg.” One could also argue the same with the movie’s handling of, and in this case, omission of weighty domestic scenes. Had the film included more of them, the movie’s script would have certainly had to accommodate the extramarital affair that Ellen and Hooper have in Peter Benchley’s novel. Left out, however, their frustrations must be suppressed and evoked as silences and omissions. In light of Spielberg’s obsession with the theme of familial dissolution, this is a notable absence. Spielberg, who started out as a TV director, once stated that “television replaced the father” in America. There are problems, yes, says Spielberg, but in Jaws, there are bigger fish to fry (in Jaws 2 this is literally the case when the shark is electrocuted using a power cable). The outtakes reveal what Brody could have been as a character had Spielberg chosen to keep certain scenes. Plagued by transparent doubt, fear, and inadequacy, Martin Brody would turn into a man far less benign and emotionally peripheral. If we knew too much about him, or the things the deleted scenes tell us, we wouldn’t believe him capable of transcending his fears to overcome the shark. We know Brody is afraid, but we don’t really know to what extent or why. After all, this film is, in large part, about evasion, the greatest evasion being death. We want to sense Brody’s fears but we don’t want them spelled out because they are also our fears. On Hooper’s boat, an extraterrestrial “floating laboratory,” (foreshadowing Dreyfuss’s role in Close Encounters) Brody, drunk due to his fear of the water, mumbles, with bottle in hand, about the ineffectuality of being a New York City cop in the early 1970s, a popular story line widely explored in many 1970s films. Brody left New York City so that he could “make a difference.” A big fish in a little pond rather than a small fish in a big pond. Scale is relevant to ego. He left a place that he feared literally (NYC) only to be engulfed by a landscape (Amity Island/water) that characterizes those fears symbolically. Brody doesn’t go in the water because of a bad childhood experience (“there’s a clinical term for it,” says Ellen) that he doesn’t let his wife reveal to Hooper (us). In a film about the opacity of symbols rearing their ugly heads, men, like the shark, cannot risk full disclosure.

The line “the gun won’t fire,” uttered by Roy Scheider after each failed take, concerns a series of close-up outtakes. In them, Scheider is shown being more Scheider than Brody in his frustration as on- and off-camera merge in a fascinating way. It’s the scene where Brody, the cop on the boat, tries to shoot the shark with his pistol. Since Scheider never gets to enact the “scene” in these takes due to a faulty prop gun, he acts out his frustration as actor instead. With each take, Scheider becomes more and more angry while still trying to remain in the scene (the diegetic world). By the fourth or fifth outtake, however, Brody’s hesitance is gone, leaving only the costume of Brody. Scheider is cursing, overwhelmed by yet another technical malfunction on set on the long shoot, and a voice from the crew can be heard calming him down. Scheider’s anger is see-through and reactive; on the surface the way Brody’s never is. “The rage and anxiety of the actors fighting the shark in the last act is honestly arrived at,” writes Carl Gottlieb in Jaws Log. “It’s not only a visualization of the character’s emotions in the script, it’s a very real expression of the discontent with the process of filming.”

Quint

In the recent TV version of Jaws, Quint enters the story differently. He appears earlier, at a point I’d never seen before on TV or in the theater. In the 30th anniversary DVD edition, that I watched the day after I saw the film on TV last month, the scene is catalogued as deleted. On full-screen TV, however, the scene suddenly becomes part of the narrative. In it Quint walks over to the Amity music shop to purchase piano wire for fishing, and while waiting, cruelly taunts a young boy playing the clarinet. This was also the case with a deleted line between Cassidy and Brody, in which Cassidy tells Brody that he’s rented a house on the Vineyard with four other guys for a thousand dollars a piece. This line was included on full-screen TV, but is catalogued as a deleted scene in the 30th Anniversary DVD version. In the deleted Quint footage, the effect is caricature. A performance of male symbolism and discord, played for controlled effect, becomes over-the-top when consistently on onscreen. Like the shark, Quint is more powerful as an archetypal menace. An allegorical figure, Quint cannot be woven into the narrative by being immersed in the daily fabric of Amity. As Antonia Quirke has pointed out, Quint is the only non-diegetic character in the film. “He doesn’t come from fiction, he comes from fact. The Indianapolis. And it would be a fracturing of the rules of fiction to rehabilitate Quint because his story doesn’t belong to the film but history.” Like the shark, Quint chews the scenery, but can’t afford to chew into it too much (that’s the shark’s job after all), and, like the movie’s famous two-note ostinato, DUM DUM, DUM DUM, if overused and played exclusively, the music, along with Quint, risks becoming a straight gag. Instead, the film’s composer, John Williams, does remarkable things with the score. The music is, as Lorraine Gary puts it in the documentary The Shark Is Still Working: The Impact and Legacy of Jaws, “the movie’s extraterrestrial script.” Music, along with the shark, is both present and absent in the film.

In another deleted scene, Quint is introduced even earlier—anthropomorphically via his purple clogs, while stepping out of his truck on the way to the music shop. The unusually shaped wooden shoes resemble the body of a shark, and become parodic as they force the viewer to focus too much on Quint’s obvious expository eccentricities. In the DVD version, along with nearly all the versions I’ve seen on TV, which has comprised the bulk of my viewings, Quint is introduced at the schoolhouse meeting via a suicidal chalkboard drawing that he famously drags his nails across, making him a deus ex machina, rather than a member of the Amity community. The chalkboard drawing shows a behemoth shark swallowing a man whole. The drawing also foreshadows Quint’s death, letting us know not just that he will die, but how it will happen. He even munches on what resembles a Holy Communion wafer, or, as it’s known in the Roman Catholic Church, a host, while he tells Amity’s residents what he will require in order to slay the shark. In the Roman Catholic Church, the word host is derived from the Latin, hostia, which means “victim” or “sacrificial animal.” Out of the three men, he will be the one to perish.

In another deleted scene, Quint is introduced even earlier—anthropomorphically via his purple clogs, while stepping out of his truck on the way to the music shop. The unusually shaped wooden shoes resemble the body of a shark, and become parodic as they force the viewer to focus too much on Quint’s obvious expository eccentricities. In the DVD version, along with nearly all the versions I’ve seen on TV, which has comprised the bulk of my viewings, Quint is introduced at the schoolhouse meeting via a suicidal chalkboard drawing that he famously drags his nails across, making him a deus ex machina, rather than a member of the Amity community. The chalkboard drawing shows a behemoth shark swallowing a man whole. The drawing also foreshadows Quint’s death, letting us know not just that he will die, but how it will happen. He even munches on what resembles a Holy Communion wafer, or, as it’s known in the Roman Catholic Church, a host, while he tells Amity’s residents what he will require in order to slay the shark. In the Roman Catholic Church, the word host is derived from the Latin, hostia, which means “victim” or “sacrificial animal.” Out of the three men, he will be the one to perish.

Lorraine Gary (Sea of Men)

Lorraine Gary, who reprised the role and made a woman central to the Jaws story in Jaws 4: The Revenge (her marine biologist son is even the father of a little girl in the movie), is allowed to do so only as a mother protecting her cub and confronting her female rival in the form of a shark, who is also an angry mother chasing her enemy across oceans in the fourth installment. As another woman, the shark in Jaws: The Revenge is on par with a slew of other cinematic feminist backlash. Think of the maternally territorial Ripley when she calls the feminized Alien a “bitch” in Aliens and Annabella Sciorra and Rebecca de Mornay fighting over nature vs. nurture in 1992’s The Hand That Rocks The Cradle. Gary is only permitted to take center stage in the film’s fourth sequel as mother and widow. Not only were many of Gary’s outtakes and story lines cut in Jaws (in particular her character’s affair with Hooper), which she openly laments in The Making of Jaws documentary, but in the movie she is often obscured. Ellen Brody’s affair is cut not only to salvage the integrity of Hooper’s manhood and the homosocial camaraderie between him and Brody—Brody would fail to rise to the heroism that is required/destined of him without the help of both men—but because in a film that purges itself of the feminine, as Stephen Heath argued, Ellen is stripped of material, and thus, screen time. She is either shot from the back, a feminine specter and witness in a male parable, or in profile, a window to it. Gary’s deleted “otter monologue,” her biggest talking-scene, was cut entirely from the movie. Interestingly, the marginalization that Gary suffers as “wife” in the film bleeds into her marginalization as actress in a male-dominated story, and the expression of boredom and mild irritation on Brody’s face when Gary does the otter monologue, is virtually indistinguishable from Roy Scheider’s.

The Child As Father To Man

A paternal role reversal is illustrated in the dinner table scene between Chief Brody and his youngest son Sean in the form of gestural mirror-play. Directly following the scene in which Mrs. Kintner publicly shames Brody for her son’s death by slapping him, the film cuts to a sepulchral Brody sitting across from his own son, drunk and silently wallowing in a shame so deep he cannot speak. Here Brody, immersed in an emasculating despair, shrinks to child-size, and Sean, as his father’s pocket-mirror, becomes the symbolic representation of that regression to infantilism. As a mock child, Brody’s fears are physically caricaturized (using symbols) and copied by his son. In Brody’s urge to evade responsibility as police chief, father, husband, and shark fighter, a mirror-image is produced and Brody becomes the little boy looking into it. The role reversal, with its early signs of Spielberg’s man-boy leitmotif—fully fleshed out in Close Encounters and ET— is complete when Brody asks his son, who has become the father, to “Give us a kiss.” While Antonia Quirke has argued that Brody asks his son for a kiss because he is too ashamed to ask his wife, I would argue that Brody asks his son because in that moment he is not a man and therefore seeks paternal, rather than marital, solace. And finally, the monster gurn Brody makes at his son, and that his son mirrors back, is the monster maw (death) Brody fears in the shark.

Hunt in The Water (The deleted version)

Whenever anyone but the three male leads go out to look for the shark, they come up empty-handed. When half of Amity’s local fisherman and resident misfits go hunting for the water monster (Dirty Harry-style) to collect the $3,000 Kintner award and do not so much as even spot the otherwise ubiquitous killer, it is proven that the movie’s shark is not a literal monster but a symbolic one. Not just anyone can catch it, or even see it for that matter. For, as Quint points out at the schoolhouse meeting, it’ll take $3,000 just to find him.

The Shark Is Still Working

Since Jaws is a movie about men, it’s not surprising that its fan base, which the three-hour (still unreleased) documentary The Shark Is Still Working: The Impact and Legacy of Jaws testifies to, consists primarily of men (white men) too—ranging from directors, producers, and screenwriters to actors and viewers. When Carl Gottlieb was interviewed for a six-part, year-long tribute to the films of Steven Spielberg on the blog talk radio program Movie Geeks United! and asked if, during the production of Jaws, he believed in Spielberg’s talent as a director, Gottlieb states that he believed in “Spielberg’s commitment to movies.” Given that tapes and DVDs weren’t available back then, explains Gottlieb, a director’s body of work was often inaccessible. If, he informs, you wanted to watch a movie, it had to be a projected screening at a film studio or at someone’s house in Laurel Canyon. And if you wanted to collect commercial film, he laughs, you had to break the law.