Invisible Missive Magnetic Juju: On African Cyber-Crime

24.10.10

“…my people simply told him to call me home with the power of his ‘Invisible Missive Magnetic Juju’ which could bring a lost person back to home from an unknown place, how far it may be, with or without the will of the lost person. So having paid him his workmanship in advance, then he started to send the juju to me at night which was changing my mind or thought every time to go home.”

“…my people simply told him to call me home with the power of his ‘Invisible Missive Magnetic Juju’ which could bring a lost person back to home from an unknown place, how far it may be, with or without the will of the lost person. So having paid him his workmanship in advance, then he started to send the juju to me at night which was changing my mind or thought every time to go home.”

-Amos Tutuola, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

I

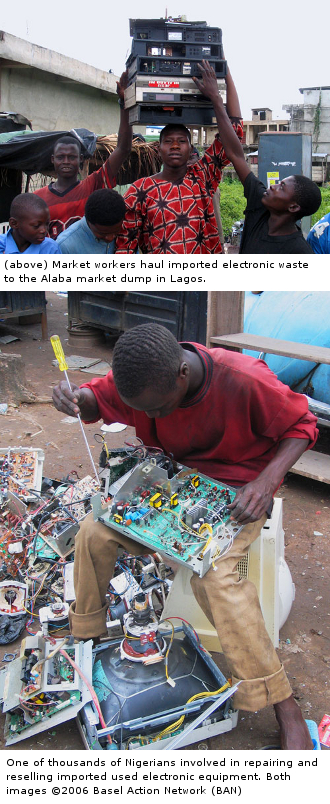

Many markets in Nigeria have areas called “computer village,” especially in places ranging from Alaba in Lagos on the West coast to Port Harcourt in the oil-ravaged Southern Delta, and over to the famous one in Onitsha in the East, where almost anything can be gotten—today’s catch from the river Niger, counterfeit medicine, locally made “foreign” goods, even dodgy airplane parts. Look through clouds of red dust for handwritten signs advertising, “computer repair,” “speedy programming” or “internet café.” Watch your step as you avoid scores of motorcycle taxis called Okadas because you could easily knock over a table scattered with the guts of cell phones which for a handful of naira will allow you to contact almost anywhere in the world. Computer village is where the detritus of Western and Eastern digitization either goes to pile up in jagged cathode ray mountains and die, or awaits repurposing in wiry bundles and circuit board batches spread across acres that simply beg for the eye of contemporary photographers like Andreas Gursky or Chris Jordan.

It’s fascinating to imagine how these blank-screened cadaverous wholes and frayed bits and pieces have all gotten here. There’s so much black glass that it is like the landscape of an indecisive volcano. These used computers have been donated by Western charity organizations and faith-based NGOs and given the Nigerian tendency to use things even beyond their given function or recognizability, their presence here is only temporary. A great many were brought from Ghana or up from South Africa while a steady stream arrived from China even before that country began its obsessive courting of West and Central Africa. But the vast majority of these machines, parts and components have been shipped by or brought in by enterprising Nigerians who since the late 1980s have known that what would mark this generation of West Africans more than blight, violence or corruption was a hunger for Web-based connectivity, that narcotic rush of shared information.

With almost no formal education whatsoever, many would learn how to rig, rewire, rebuild and master the essentials of computing in these glorified junkyards. They learned from ragged men with soldering irons in their pockets that pushed wheelbarrows filled with screens, wires and keyboards, with the wild-eyed look of juju men drunk on that vile moonshine called ogogoro.

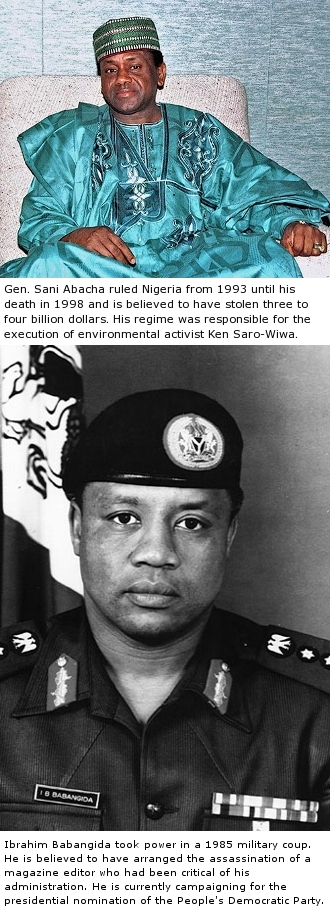

This hunger for information wasn’t generated simply by the dubious pleasures of globalization made available by satellite TV or the cloud of privilege that hovered above those lucky enough to travel back and forth between Nigeria and London, or West Africa and the United States. This desire for information was generated by decades of forced national myopia. And it was due to a series of military dictators who appeared on the scene just as the over-developed world was going digital. The government’s intense denial of information as well as the emerging access to it during that period had much to do with the hunger for global connectivity and lust for economic growth that has characterized these last thirty years of West African social and cultural life, this seemingly endless “mourning after.”

Should Nigeria ever get serious about developing a tourist trade, it shouldn’t present itself via clichéd sub-tropical idylls of heat, rhythm and sex: God knows Ghana and Kenya have made their inroads there, following on what could be cheekily called “the Caribbean model.” And it shouldn’t present itself via the equally idyllic but increasingly bizarre thing known as “heritage tourism.” This latter blurs the line between pilgrimage and tourism, catering primarily to African-Americans by appealing to that American lust for an identity that can be purchased and a history that can be exchanged. Nigeria should aim for the increasingly lucrative world of “eco-tourism.” No gawking at maudlin endangered species, fragile landscapes and eco-systems on display and no necessarily melodramatic rendering of slavery’s impact. It should show its visitors where all of their waste, all the once shiny products of America, Europe and China, inevitably ends up—the “computer villages” or the various computer graveyards that shadow them. With no means of recycling beyond the needs and imagination of those who sift through it, with no treated or prepared space for its dismissal, to confront this waste, our waste in a place like this is something that would tremble and humble Dante.

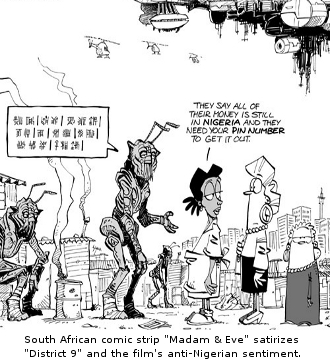

Two not unrelated things come immediately to mind in this setting. First, the contrast of shantytown Africa and alien machine technologies that inspired Neill Blomkamp’s brilliant but Nigeria-bashing film District 9; second, science fiction writer William Gibson’s now hackneyed yet still prescient “cyberpunk” mantra, “the street finds its own uses for things.” For those who have forgotten the latter, it’s from Gibson’s novel Neuromancer, famously the origin of the term “cyberspace.” In it he routes the “consensual hallucination” of the Web through a narrative of dizzying globality, a world where “the West” has been de-centered by pirated technological refuse and unceremoniously hacked networks of privileged information. That Nigeria has become the home of what many consider the greatest threat to the information super-highway, and that that threat emerges largely in and around these “computer villages” as well as shanty-ish Internet cafés suggests that it was no mistake that the first clear face we see in Neuromancer is that of a tribal-scarred West African, a silent witness to his/our future.

It is no stretch to suggest that Gibson’s Neuromancer and other “cyberpunk” texts helped make District 9 possible alongside any number of contemporary science fictions set in non-Western climes—China, Brazil, India, the Middle East and Africa. Because of this work, it became possible to imagine a world where the Internet would be appropriated and possessed—as with the Voodoo pantheon in his follow-up Mona Lisa Overdrive—by the spirit of alternate cultural imaginations. Gibson’s enigmatic use of Caribbean music and culture in the context of digital technology and web-piracy has much to offer in making sense of African cyber-crime.

But if Bangalore can be credibly called the “Silicon Valley” of India, it seems necessary to find some similar sobriquet for Nigeria because its place in the world and history of the Internet is equally assured. Granted, for different reasons and quite notorious purposes. India’s high tech edge was in part due to the colonial legacy of the English language and a massive, highly educated young population. For this generation of Indians, modernity and Westernization were not necessarily synonymous and the embrace of the latter came with few of those fears about the erosion of tradition that were present amongst the generation that led the fight for colonial independence. Nigeria’s Internet presence was fueled by that same dynamic.

The difference? Those dictators. This series of rulers eviscerated the nation’s educational system, fomented the “brain drain” and so over-committed the country to oil that all other possibilities for self-development seeped into red dirt before they could be fully fleshed. It was the birth of the kleptocracy. Corruption in this period, from the early 1980s to the very late 1990s, became so indigenized as to be indistinguishable from anything anyone could call “tradition.” Due to this series of catastrophes India has become a primary site of Internet outsourcing while Nigeria is home to the now legendary advance fee scam, or “419,” named for the Nigerian criminal code for fraud. These scams emerged following the trail of oil wealth during the era of the dictators but arrived fully developed at everyone’s doorstep with computers. That they began as local hand-written letters, then traveled globally with the introduction of fax machines and the Internet, and are now disseminating wildly with SMS and cell-phones shows their tandem evolution with communications technology in West Africa.

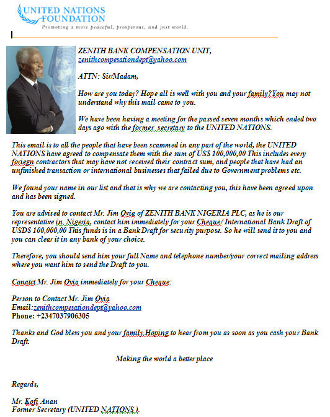

Though the 419 letters generally register as broken-formal versions of 19th Century epistolary narratives—the scammers have been dubbed “frustrated novelists-in-crime”—they are really the public face of West Africa’s intimacy with digital media and technology and of Nigeria’s refusal to wait passively for either justice from their political system or global charity. Few outside of Nigeria, however, take them seriously and are stunned to learn that so many people in so many countries and of all social and educational levels regularly fall for them. Yet official statistics suggest that they bilk the United States of billions of dollars per annum and even more in the UK. Now that they’ve set their sights on China and India after a generation assaulting Singapore, Australia, Ukraine and everywhere else in the world, there is more for them to gain. With the global economic downturn affecting not only foreign aid but also the remittances sent home by Nigerian immigrants that help sustain the country’s economy, we should brace ourselves—for more of those slightly comical, strangely earnest emails that clog our inboxes and promise us intimacy with a world that might be as excitingly unstable as it seems. They script a world as magical as it is profitable in its sprawl, in which a letter from, say, Ban Ki Moon and the United Nations, or the troubled wife of some beleaguered ex-president, or a pastor from a church whose parishioners are mightily oppressed by some vaguely familiar genocidal state could plausibly appear on your screen.

By rendering the Web an unsafe bush of cross-cultural and economic exchange, these scams have become ingrained in our cultural landscape. It is stunning that they have become so easily normalized in the global popular imagination and media environment. We laugh at or about them. Some Americans collect and display them, going so far as to devote time and effort to equally theatrical and sometimes quite racist “counter-scams.” The strangest thing about these emails is this: they have become such a part of our lives and the lives of banks, lawmakers, the FBI, Interpol, Scotland Yard, The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, innumerable private citizens without us balking at the notion, the very idea of cyber-crime from a country that has no regular electricity, no running water, little access to computer technology, barely any complete roads to speak of and much of whose populace survives on less than one US dollar a day.

To put things in perspective, even with optimum access from an Internet café in Nigeria it can take many hours to download a single song from iTunes or may take days to retrieve a simple document. Yet a 419 pulled off the third largest bank theft in history: Banco Noroeste in Brazil in 1998. They have robbed Merrill Lynch, impersonated governments and hustled government officials, and done irreparable damage to the reputation of Nigeria and its legitimate business sector. They have come close to perfecting the art and skill of website construction and flooded the world with fake checks and dreams of illicit gain. Most recently they’ve begun roping in Americans as willing fronts to their activity. This industry is far more than just about the letters though it is true that as recently as 2002 the US Department of Justice in New York opened up every item of mail from Nigeria passing through JFK Airport by court order. Approximately 70% involved scams.

To put things in perspective, even with optimum access from an Internet café in Nigeria it can take many hours to download a single song from iTunes or may take days to retrieve a simple document. Yet a 419 pulled off the third largest bank theft in history: Banco Noroeste in Brazil in 1998. They have robbed Merrill Lynch, impersonated governments and hustled government officials, and done irreparable damage to the reputation of Nigeria and its legitimate business sector. They have come close to perfecting the art and skill of website construction and flooded the world with fake checks and dreams of illicit gain. Most recently they’ve begun roping in Americans as willing fronts to their activity. This industry is far more than just about the letters though it is true that as recently as 2002 the US Department of Justice in New York opened up every item of mail from Nigeria passing through JFK Airport by court order. Approximately 70% involved scams.

Internet 419 has merely been the advance guard of Nigerian gangs focused on international financial and electronic crimes. Though belied by the ramshackle modesty of Internet cafés that are deafening with the hum of portable generators and full of scammers from opening to close, it is an industry with innumerable outposts, masks and hierarchies. Arrests, scams, check- and money-laundering schemes and staggering losses have been identified in over thirty-eight countries. All orchestrated largely online and largely from what one journalist called “the most successful culture of financial fraud in history.”

It is hard not to be impressed. It should make us rethink commonly held assumptions about the “digital divide” as well as extant stereotypes of passive Africans whose suffering is their only virtue. These are the people Thomas Friedman forgot about in his much-lauded celebration of the wonders of globalization and the Internet, The World is Flat. And you know he must have received his share of the emails. One wonders if our casual acceptance of these scams and the ease with which they have been turned into humor might have something to do with how the Western world generally feels about Africa and Africans. It is possibly due to the fact that the scammers and their fake websites, counterfeit documents and intricate global network come from a place we are unused to linking to sophisticated technology or to this level of guile. So we still do not take them seriously. Many of the letters actually play on this combination of “African” innocence and venality. They push forward with a brash, hyperbolic naiveté that easily reduces the guard of those who fall victim to them. After all, could you really be duped by someone with such atrocious grammar?

It’s a classic con, the first rule of which is that you first convince the victim that you the conman are an utter idiot. This is easy because unlike in their relationships with African-Americans, most whites do not fear Africans. The second rule is to engage the victim in a conspiracy, one in which both of you are on the edges of guilt if not in the midst of full culpability. The scams generally spin out over long periods of time, requiring layers of deceit and increasing amounts of investment from the victim and performance from the hustler. That conspiratorial intimacy keeps them afloat over time and space. It is also responsible for one of the most curious psychological aspects of these scams. After investing x amount of money, it becomes easier and easier to invest more. Desperation mutates into an aggressive form of trust. Victims begin to flagrantly display their vulnerability, sending money blindly into the void. At a certain point of loss, all one can expect are miracles. Because these crimes are rarely reported to the authorities or admitted to anyone out of shame (this being one of the rumors why Japan has been so lucrative for the fraudsters in recent years), most estimates about the international scale of the letters and their profits are therefore conservative.

It’s a classic con, the first rule of which is that you first convince the victim that you the conman are an utter idiot. This is easy because unlike in their relationships with African-Americans, most whites do not fear Africans. The second rule is to engage the victim in a conspiracy, one in which both of you are on the edges of guilt if not in the midst of full culpability. The scams generally spin out over long periods of time, requiring layers of deceit and increasing amounts of investment from the victim and performance from the hustler. That conspiratorial intimacy keeps them afloat over time and space. It is also responsible for one of the most curious psychological aspects of these scams. After investing x amount of money, it becomes easier and easier to invest more. Desperation mutates into an aggressive form of trust. Victims begin to flagrantly display their vulnerability, sending money blindly into the void. At a certain point of loss, all one can expect are miracles. Because these crimes are rarely reported to the authorities or admitted to anyone out of shame (this being one of the rumors why Japan has been so lucrative for the fraudsters in recent years), most estimates about the international scale of the letters and their profits are therefore conservative.

Most importantly this conspiratorial tone is crucial to the ethics of the scammers, locally called “yahoo boys” after their beloved ISP, one of the first to be freely available in Nigeria. Ethics, because if the success of the 419s depend a great deal on how the developed world sees Africa and Africans, so are they an index of how many Africans see the over-developed world. Yahoo boys certainly know they are breaking the law but are not necessarily convinced that what they are doing is a crime, especially if the so-called victim willingly participates in a clearly suspicious scenario. To respond is to comply, eyes-open, blinded by your own greed. The money offered you, after all, comes in sums far too large to be legal. The letters generally make clear that the transaction functions in some trans-national gray area, hence the need for haste and secrecy. This, however, is only true for the Advance Fee scams. There are myriad others that don’t function this way but it is the structure to which the yahoo boys almost all refer to for justification. To speak with them and move through the culture that has sprung up around them in Lagos—beer parlors and night clubs on Allen Avenue, Chinese restaurants in the suburb of Ikeja or on Victoria Island where real money displays itself—is to hear talk largely of the morality of it all.

In some ways this is not surprising. Nigeria is a barely secular country and the yahoo boys to a man are very religious, Christians mostly since it is in the South and South West that these crimes and this culture are largely clustered. The largely Muslim North has always been cautious of and resistant to Western education and technology, which is also why it is taken for granted that 419 must have been developed by Igbos. Igbos were among the first to embrace Christianity and Western education in Nigeria and are most often victims of the genocidal fury of the North. Since the Nigerian Civil War in which that fury was most notoriously expressed ended in 1969, they have felt kept from their share of the country’s wealth and political power.

This religious dimension is important to mention because a number of long-shot journalists and paranoid pundits in America have argued that since Nigeria had one of the largest Muslim populations in the world the scams were a form of cyber-terrorism to fund Al Qaeda. It didn’t help that Osama Bin Laden had around that time made it public that Nigeria should be targeted for radicalization. The yahoo boys however are more free-market fundamentalist than they are religious fundamentalist. Instead of bowing to Mecca, they are more likely to pray to Seattle, home of Bill Gates and Microsoft.

This religious dimension is important to mention because a number of long-shot journalists and paranoid pundits in America have argued that since Nigeria had one of the largest Muslim populations in the world the scams were a form of cyber-terrorism to fund Al Qaeda. It didn’t help that Osama Bin Laden had around that time made it public that Nigeria should be targeted for radicalization. The yahoo boys however are more free-market fundamentalist than they are religious fundamentalist. Instead of bowing to Mecca, they are more likely to pray to Seattle, home of Bill Gates and Microsoft.

Yet the obsession with ethics is also not surprising because to speak of morality in the context of Africa, the West and crime, is to speak inescapably of colonial history. However disingenuous or insincere their arguments may at times seem, most yahoo boys are clear about their relationship to continuing forms of economic and political domination. Or, at least, they are clear about their mastery of this language of guilt and innocence, global victimization and responsibility. So to speak of 419 is to speak inescapably to the fragile and dubious architecture of foreign aid, debt and charity that undergirds the West’s continuing under-development of the African continent. It is also to address the complex and often inadequate ways that many on the continent respond to their own predicaments.

II

“Oyinbo man I go chop your dollar,

I go take your money disappear

419 is just a game,

You are the loser I am the winner…”

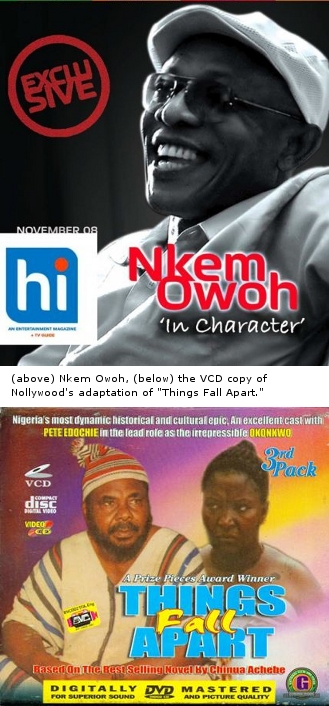

Nkem Owoh, “I Go Chop Your Dollar.”

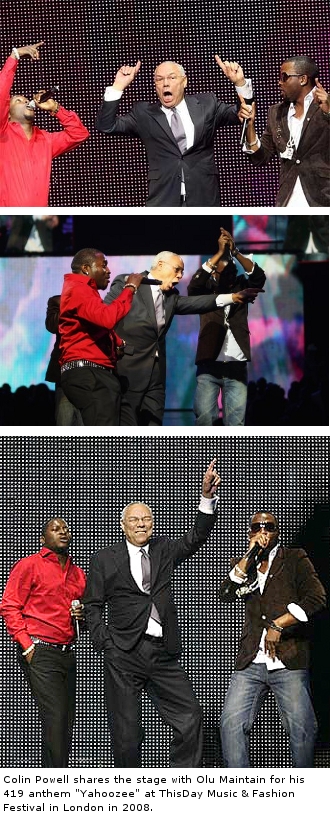

Although Olu Maintain’s hip hop flavored 419 anthem “Yahoozee” has spawned numerous imitators, the song that really put the yahoo boys on the map as urban icons was the actor/comedian Nkem Owoh’s “I Go Chop Your Dollar” (2005). “Yahoozee,” by the way, has become infamous in the Nigerian Diaspora as the song to which former US Secretary of State Colin Powell can be found online dancing to at a cultural event in London in 2008. Though clearly unaware of the song’s meanings or lyrical content, that Powell used the song and its accompanying dance as background to his statements about “black” or African pride makes the moment even more fantastic. The audience he was addressing was an Africa far different than the one in his august imagination.

Unlike “Yahoozee’s” mimicry of the flash and bling of an early/mid-90s African-American hip hop video (an era and style which much Nigerian pop is sadly, still in thrall to), Owoh’s infectious song and rickety video actually frames the ethics of 419ers in the most accurate way; so accurate in fact it was quickly banned in Nigeria. It is worth noting that Owoh (a.k.a. Osuofia) first came to attention in the film of Chinua Achebe’s classic 1958 novel Things Fall Apart, the hands-down primary text in Nigeria’s—if not West Africa’s—framing of the historical terms of colonial debate. It is also worth noting that in 2007 Owoh was arrested by Dutch police for alleged participation in a massive 419 scam that included both lottery and immigration fraud, though he was later released pending further investigation.

For most Nigerians “I Go Chop—[I will eat]—Your Dollar” is a guilty pleasure or an outright embarrassment. For the yahoo boys it is a manifesto. It argues that for those for whom “poverty no good at all,” Internet hustling is not a crime, “just a game” in which the only ones who fall are the “mugu”—Nigerian pidgin-slang for mark, sucker, rube or fool. The taunting refrain “you be the mugu, I be the master” emphasizes the terms and the pleasures of a reversal of roles that in this case produces concrete dividends and no end of bragging rights. The historically greedy Oyinbo—“foreigner/white man”—is here the loser, the fool and the cunning African trickster using the white man’s machines finally is or can be the winner.

For most Nigerians “I Go Chop—[I will eat]—Your Dollar” is a guilty pleasure or an outright embarrassment. For the yahoo boys it is a manifesto. It argues that for those for whom “poverty no good at all,” Internet hustling is not a crime, “just a game” in which the only ones who fall are the “mugu”—Nigerian pidgin-slang for mark, sucker, rube or fool. The taunting refrain “you be the mugu, I be the master” emphasizes the terms and the pleasures of a reversal of roles that in this case produces concrete dividends and no end of bragging rights. The historically greedy Oyinbo—“foreigner/white man”—is here the loser, the fool and the cunning African trickster using the white man’s machines finally is or can be the winner.

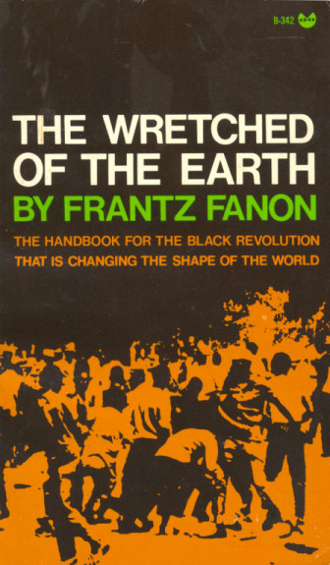

Whether yahoozee know it or not, this upending of values, as Frantz Fanon famously explored in The Wretched of the Earth, is central to the colonial mise-en-scéne wherein the “native” is always evil and the colonial power the source of all that is good. And hearkening back to the work of the great German anti-philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, Owoh’s reversal is a form of ressentiment, which if it sounds very like resentment to you was part of Nietzsche’s meaning. To resist any status quo is often to reverse its moral standards. It is to willingly if not joyfully do evil or at least upend the system of value that defines good or evil. That was the other part.

“I Go Chop Your Dollar” goes on to argue that “When Oyinbo play wayo”—“wayo” meaning tricks or games or hustle—they merely call it “a new style;” but when a common Nigerian does it “them go dey shout: bring ‘am, kill ‘am, die!” That, in Owoh’s view, is not only hypocrisy but was actually due to a first reversal in which Africans naturalized or accepted “corrupt” Western values in the first place. In less oblique words, from this perspective the Western world has no right to describe any country as corrupt; and it is naïve if it doesn’t acknowledge that resistance to its power includes if not demands crime.

If all of this seems a familiar form of self-justification and a dependence on racial or cultural innocence to advance a dubious cause, it should. You’ve read it before in existentialist literature from Dostoevsky to Camus to Jean Genet to Richard Wright. But you’ve heard it primarily in reggae and hip hop, forms of black music that often assert crime as an act or metaphor of resistance/liberation and where “oppression” is all too often claimed as a justification for almost anything. That a great many victims of these crimes are themselves black and from the trickster’s own community seems always ignored in these narratives. And yahoo boys generally don’t do redistribution. They rarely re-invest in the public good and instead become even gaudier members of an already gaudy West African elite. A real Robin Hood has yet to appear. This certainly betrays much of the colonial politics of their justification but not all of it, since it is hard to fault their historical logic. But that elite, which has directly participated in the under-development of Nigeria alongside Western colonialism is one the yahoo boys slavishly imitate and to which they quite nakedly aspire.

This latter point should also sound familiar, since for all their revolutionary gestures, reggae and hip hop often seem far more motivated by economic envy than by social justice. Reggae and hip hop (along with r&b) are, unsurprisingly, primary cultural influences on that transnational phenomenon of yahoozee. Admirably, this industry is still without the kind of violence that usually accompanies organized crime. Nigerians, it must be said, pride themselves on their general hostility to violence (barring, of course, the occasional religious/ethnic flare-up in the North or the lurid stoning and burning of market thieves which occurs far too often to even acknowledge). So for the yahoozee, theirs is a bling without the lethalness: it’s more Diddy than it is Fiddy. It is no exaggeration to say that for most of the yahoo boys Internet crime is merely a form of reparations—not necessarily for slavery, since their traumas are only tangentially connected to the concerns of African-Americans and Caribbean or European blacks. These “Diaspora” blacks are as much oyinbo as they are mugu. The only difference between them and whites is that they are most easily conned by the language of, well, “black” or African pride.

This latter point should also sound familiar, since for all their revolutionary gestures, reggae and hip hop often seem far more motivated by economic envy than by social justice. Reggae and hip hop (along with r&b) are, unsurprisingly, primary cultural influences on that transnational phenomenon of yahoozee. Admirably, this industry is still without the kind of violence that usually accompanies organized crime. Nigerians, it must be said, pride themselves on their general hostility to violence (barring, of course, the occasional religious/ethnic flare-up in the North or the lurid stoning and burning of market thieves which occurs far too often to even acknowledge). So for the yahoozee, theirs is a bling without the lethalness: it’s more Diddy than it is Fiddy. It is no exaggeration to say that for most of the yahoo boys Internet crime is merely a form of reparations—not necessarily for slavery, since their traumas are only tangentially connected to the concerns of African-Americans and Caribbean or European blacks. These “Diaspora” blacks are as much oyinbo as they are mugu. The only difference between them and whites is that they are most easily conned by the language of, well, “black” or African pride.

It was the former military dictator Ibrahim Babangida who helped mature the 419. In deregulating the foreign exchange market and the Nigerian banking system in 1990, the already fragile local currency—the naira—spiraled downwards. As the naira lost value, foreign currency became absolutely necessary. The 419s then began to aggressively engage the far ranges of global capital as an outgrowth of the now legitimate culture of the “shady deal” in Nigeria. The reparations the yahoo boys claim are rooted in the values of that moment, for their portion of the “national cake.” In a culture where tradition can mean both entitlement and extortion, they set out for a cut of the aid money squandered by corrupt leaders like Babangida whose billions are still untraceable and who has currently threatened to become “president” again! The yahoo boys want their share of the oil money that has been stolen and siphoned off so often and so openly; and likewise, of the gold, copper, rubber, tin. And like so many in the Congo region, they are claiming the coltan (columbite-tantalum) so important to our cellular phones, video games and laptops and which makes sections of certain “computer villages” so dense with trade and wreckage as to be truly forbidding.

That these songs and videos have only appeared in the last few years when the scams date back to the 1980s suggest that the iconic self-identity of 419 has emerged only recently as the term has moved from a humble legal classification into a worldview and a lifestyle. For some time now 419 has meant far more than fraud in Nigeria or Internet crime. It describes a cunning gambit or an unorthodox, shady but impressive way of doing things, as in “don’t 419 me-O!” or “did you see the way he 419-ed her?” It is also used to describe people who live a life far beyond their means and whose obsession with flash, style, cash and cars—what used to be called the “high life” back in Nigeria’s oil-boom 60s and which was also a form of popular music—can only be suspicious in a country with such a dramatic division between those who have and those who just stare.

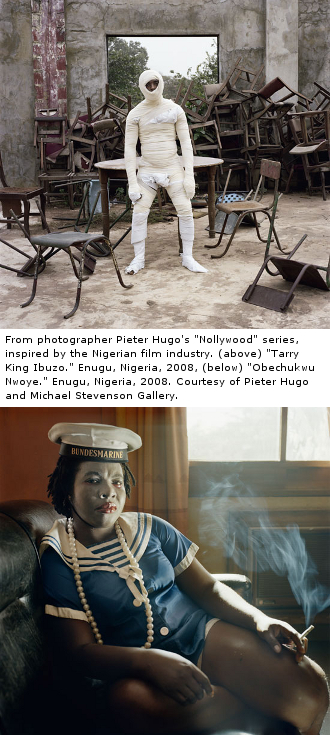

The disdain or ambivalence that most Nigerians feel for the 419ers is belied by the fact that those scams and the resultant culture have had a broad impact on its contemporary culture and society. This is especially the case now that many in other African countries are setting up their own cyber-crime franchises. The term 419 speaks not just to a sensibility but an entire generational coming-into-being. Just follow the trail of money. Chart all that the money has either triggered or shared social or historical space with. The generation of 419 is that of Nollywood films, for example, which really began humbly on VHS in the very early 90s and has since outpaced the U.S. film industry to become second only to India’s Bollywood in scale. That the dictators helped shut down access to information only made Nigerians turn to their own resources. And like Bollywood, it is an industry symbiotic with the rabid pirating of American films, music and media that is also a lucrative part of the Nigerian movie business. 419 also evolved alongside an exploding indigenous urban popular music and culture that is no longer dependent on external influences for mimicry or validation and now has the impact on the rest of sub-Saharan Africa that African-America once had upon the world. Nigeria may have failed sub-Saharan Africa in the expectation that it would become the continent’s great economic and political super-power alongside a free South Africa; but with its current cultural influence, it might be finally living up to at least a part of its promise.

In truth, the yahoo boys do have sympathizers. Not simply those who benefit from their stimulating of the local economy, there are also those who admire the ingenuity necessary to pull off some of these elaborate scams and who can’t help but feel some nagging sense of historical justice at work. Again, it’s hard not to be impressed, especially when you know that bank presidents and erstwhile highly educated Westerners have disembarked in Lagos to deliver money and sign oil contracts not worth the red dirt clumping beneath their shoes; or if you’ve seen the pin-point performance of those who greet them, and whisk them from airport to hotel in limousines while dropping the name of rock star Bono or quoting his mentor the economist Jeffrey Sachs when in truth they have barely a high school education.

It is tragic and hilarious to know that so many of them boast of having their own NGO, funneling money into their own pockets after becoming fluent in the language of international aid-speak and Western guilt-charity. It is hard not to experience a combination of awe and disgust at the fuzzy tears on webcam of men and women from the American Midwest or English Home Counties pining away for their one true love there struggling against the elements or the godless, or who works so hard for their church/the U.N./the government/the Peace Corps that sending them a mere hundred dollars seems woefully inadequate.

419ers also know that a great many of their most prominent critics benefit from their exploits. Due to the success of these scams, they are in effect an economy parallel to oil, which is to say that in a country like Nigeria, all of these large-scale activities can be traced upwards into the elite and into the government. This is something rudely discovered by Nuhu Ribadu, the former head of the Nigerian Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and possibly the most trusted and therefore feared man in Nigeria. It was he who pointed out that despite the fact that hundreds of Nigerians had been jailed for these scams in scores of countries, his country had failed to prosecute or convict just one. His subsequent campaign against the 419 cartels as well as generalized corruption not only regularly almost cost him his life, it eventually had him ignominiously “redeployed” by the President in 2007. He dared look and burrow too far upwards. He dared make public what was already public: a culture in which 419 is not the crime but the most globally recognized symptom.

419ers also know that a great many of their most prominent critics benefit from their exploits. Due to the success of these scams, they are in effect an economy parallel to oil, which is to say that in a country like Nigeria, all of these large-scale activities can be traced upwards into the elite and into the government. This is something rudely discovered by Nuhu Ribadu, the former head of the Nigerian Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and possibly the most trusted and therefore feared man in Nigeria. It was he who pointed out that despite the fact that hundreds of Nigerians had been jailed for these scams in scores of countries, his country had failed to prosecute or convict just one. His subsequent campaign against the 419 cartels as well as generalized corruption not only regularly almost cost him his life, it eventually had him ignominiously “redeployed” by the President in 2007. He dared look and burrow too far upwards. He dared make public what was already public: a culture in which 419 is not the crime but the most globally recognized symptom.

These scams are now old enough and have been lucrative enough that the yahoo boys almost comprise an actual class in Nigeria. The cars, the clothes, the parties, the celebrity culture, the magazines, nightclubs; some of them have even managed to achieve prominent legitimate positions, in some cases in banks. This proto-class includes those who are not themselves scammers but aspire to, benefit from and partake of the lifestyle. For example those very many lovely young women used as fronts for romance scams in which your email correspondence or Instant Message is being scripted by a 419er, but when you ask for photos or web-cam images she shows up smiling (that is if you’re lucky: many just cop images of models and pop stars from the internet). It also includes women who engage in these romance scams themselves, a long-distance form of celibate prostitution.

This lifestyle now includes people like Nkem Owoh and Olu Maintain; those who sing songs that manage to help generate the mythic swagger of yahoozee. If you keep in mind the parallels with reggae and its long love affair with “rude-boys,” or hip hop and its obsession with thugs, gangstas and hustlers, this swagger may not be unfamiliar; it might even be trite.

However, like most thugs, gangstas, rude-boys, Trinidadian bad-johns and South African tsotsis, yahoo boys really are on the low end of the totem pole. In the larger context of things it is hard to begrudge them their fantasies and public pleasures. Almost none of them even own computers. The ones driving hummers through the dirt and barely paved roads of Lagos blasting D’banj, P-Square, Olu Maintain or R. Kelly, are either very lucky or too far up the totem pole to visit cyber cafés for fear of random EFCC raids or the occasional presence of a foreign news crew. True yahoo boys are just a few steps above those “area boys” who lurk around Lagos hungry for any opportunity to score some cash. They are the ones in the trenches. They spend hours and hours from dawn till nighttime phishing with customized email extractors, sending out thousands of emails per day and waiting for that one “hit” that may lose the victim a few dollars, pounds or yen but is enough to keep them going for weeks.

Because the numbers in each scam are astronomical—you are promised billions in exchange for hundreds—and even though the scams bring in billions (one estimate for last year put it at $9.3 billion from America alone), most of what each individual yahoozee gets is much more modest. They may score in the hundreds if they are organized and if connected, possibly thousands. Most victims actually back off from the scam after losing, for example, the $200 that they’ve been asked for to cover a “processing fee” so that the “agent” or “Madame ex-First Lady” can get the untold millions to you which, of course, you are only holding in your account and will be paid interest on those untold millions.

Because the numbers in each scam are astronomical—you are promised billions in exchange for hundreds—and even though the scams bring in billions (one estimate for last year put it at $9.3 billion from America alone), most of what each individual yahoozee gets is much more modest. They may score in the hundreds if they are organized and if connected, possibly thousands. Most victims actually back off from the scam after losing, for example, the $200 that they’ve been asked for to cover a “processing fee” so that the “agent” or “Madame ex-First Lady” can get the untold millions to you which, of course, you are only holding in your account and will be paid interest on those untold millions.

Or in the case of the “over-capitalization” frauds, you will be paid in an amount far more than you initially charged for whatever item you posted on eBay or Craigslist, for example. Just be sure to send them the difference since U.S. dollars are so hard to come by in Nigeria and you simply cannot trust local banks. Then after you deposit the frighteningly authentic looking check (bank seal, correct president and all) in your American account and have sent the item and the difference, you discover that the bank has funded the check from your own monies only to discover its falsity.

Don’t laugh: it works.

Not to mention the scams that interrupt scams to alert you that you have been scammed and that for such and such amount of money you will get back your money from these illicit fraudsters who are ruining the name and reputation of Nigeria…signed by the EFCC or Nuhu Ribadu or even the Nigerian head of state.

These are just the basic ones for those at the bottom of the totem pole to handle. They are the ones most outside of Nigeria are exposed to. They are not what broke Banco Noroeste, or that route millions through accounts in the Cayman Islands or which allow some 419ers to purchase prime international real estate that rival only that purchased by the dictators and their wives. These big scams require planning, a full cast and crew, research and a level of organization that were it ever applied to Lagos itself would transform that city into a self-sustaining, debt-free nation. The main point is that it only takes a handful of dollars from outside Nigeria to capitalize a week of yahoozee; and if you are dealing in bulk with people either unaware of the scams or who simply couldn’t imagine them being anything but true you will realize that in a global market, there is a mugu born every minute. Millions of them log on every day.

Sadly and despite the considerable merits of their nation and their diaspora, Nigerians will always be linked in some way to the 419. The younger generation in particular: they now controversially define themselves as “Naija,” signaling a departure from an older generation stuck between Western charity and local authoritarians. This younger generation rolls with a swagger disdainful of global pity and deeply suspicious of “big man” politics. However, the very term “Nigerian” has come under fire by nations for whom that swagger is seen as criminal despite the overwhelming number of Nigerians contributing healthily to their cultures and economies. It is not uncommon for Nigerian hustlers in South Africa to pass as Ghanaian, or for legitimate and law-abiding migrants to cringe when asked for their passports. The term now has as complex and touchy a meaning as “Jamaican” did in the North Atlantic world during the 1970s and 1980s. This was of course when the spread of reggae music and culture became at times perniciously linked to the spread of the infamous transnational drug posses. That reggae went digital in that period while its pan-Africanism or Afro-centrism began to fade should also recall the timing and the narrative of Neuromancer with its stateless Rastafarians in deep space exile, listening to digital dub and waiting in vain for a Zion that they’d expected to find in Africa.

Given the ability to pirate, download and master everything from sound production software to film/video editing programs, this Naija generation continues to redefine the African continent just as the 419 have redefined the virtual “eighth continent” of the Internet. It is this sense of continental competition that motivates the xenophobia of District 9, which was promptly banned in Nigeria. Admittedly this representation of Nigerians was aided and abetted by the presence of a Nigerian criminal class that began crossing into South Africa the very moment apartheid was struck down. That this African science fiction would represent Nigerians as so brutally primitive, however, goes directly against their known sophistication. It is partly their tech savvy that made them initially welcome in South Africa as it attempted to reinvent its economy along non-racist lines. To describe Nigerian criminals as prone to the level of psychopathic violence that the film depicts is beyond hyperbolic. It manages to equate Nigerian crime with the kind of violence that accompanied the dispersal of Jamaican drug posses. This is perhaps why the main Nigerian crime lord in District 9 looks like a reject from Stephen Seagal’s paranoid 1990 anti-drug posse film Marked For Death, in which he battles drug-crazed, voodoo-worshipping Rastafarians prone to human sacrifice.

Given the ability to pirate, download and master everything from sound production software to film/video editing programs, this Naija generation continues to redefine the African continent just as the 419 have redefined the virtual “eighth continent” of the Internet. It is this sense of continental competition that motivates the xenophobia of District 9, which was promptly banned in Nigeria. Admittedly this representation of Nigerians was aided and abetted by the presence of a Nigerian criminal class that began crossing into South Africa the very moment apartheid was struck down. That this African science fiction would represent Nigerians as so brutally primitive, however, goes directly against their known sophistication. It is partly their tech savvy that made them initially welcome in South Africa as it attempted to reinvent its economy along non-racist lines. To describe Nigerian criminals as prone to the level of psychopathic violence that the film depicts is beyond hyperbolic. It manages to equate Nigerian crime with the kind of violence that accompanied the dispersal of Jamaican drug posses. This is perhaps why the main Nigerian crime lord in District 9 looks like a reject from Stephen Seagal’s paranoid 1990 anti-drug posse film Marked For Death, in which he battles drug-crazed, voodoo-worshipping Rastafarians prone to human sacrifice.

Yet the connection between African cyber-crime and Jamaican music and culture might ultimately be prophetic. That a country like Jamaica with very little technological infrastructure has had such an unpredictable impact on high tech sound production makes the 419s a phenomenon impossible to ignore. And that a city as crime-ridden and economically deprived as Kingston would be where a colonial people use digital and electronic media to spin their own myths of liberation, memory and desire and erect a legitimate culture industry of its own—that must be kept in mind as we prepare for whatever inevitably will come next. And something will. After all, despite their growing intimacy with computers and the Internet and despite new generations being spawned in the red dirt of computer village, no yahoo boy has ever directly hacked a system.

Well, none so far.

As previous empires used to say, Ex Africa semper aliquid novi— “From Africa always something new.”

____________________

Images on p. 9 thanks to Pieter Hugo and Michael Stevenson Gallery.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

Louis Chude-Sokei on modern black face, fiction across borders and Alain Mabanckou