Talk Show 24 with Leah Hager Cohen, Joshua Ferris, Alice Mattison, and Ann Packer

30.04.09

Leah Hager Cohen was born in Manhattan in 1967. She has three children and has written seven books. Among the honors her books have received are New York Times Notable Book (four times); American Library Association Ten Best Books of the Year; Toronto Globe and Mail Ten Best Books of the Year; and Booksense 76 Pick. She is a frequent contributor to The New York Times Book Review and currently teaches writing at Lesley University’s M.F.A. program and at Boston University. Visit Leah at www.leahhagercohen.com.

Joshua Ferris is the author of Then We Came to the End, a National Book Award finalist and winner of the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award. Visit Joshua at www.thenwecametotheend.com.

Alice Mattison’s new novel, Nothing Is Quite Forgotten In Brooklyn, was published in September by Harper Perennial; an excerpt appeared a year ago in The New Yorker as a short story, “ Brooklyn Circle.” Her last book, In Case We’re Separated: Connected Stories, was a New York Times Notable Book of 2005 and won the Connecticut Book Award. Alice is the author of five novels—also including The Book Borrower, The Wedding of the Two-Headed Woman, and Hilda and Pearl—four collections of stories, and a book of poems. Her stories, essays, and poems have been in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Ploughshares, Best American Short Stories, the Pushcart Prize, and many other publications. She teaches fiction in the graduate writing program at Bennington College.

Ann Packer received the Great Lakes Book Award for The Dive from Clausen’s Pier, which was a national bestseller. She is also the author of Mendocino and Other Stories. She is a past recipient of a James Michener award and a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. Her fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and other magazines, as well as in Prize Stories 1992: The O. Henry Awards. She lives in northern California with her family. Visit Ann at www.annpacker.com.

––Where was your first apartment?

Cohen: It was on Lake Street in New Haven, just past the edge of Yale’s campus.

Ferris: My mother’s womb. A snug little efficiency, all utilities paid. No problem with heating or plumbing, though the landlord was a heavy smoker, to her eternal shame.

Mattison: The apartment was on Sacramento Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Three other women and I rented the second floor of a house that was behind another, larger house. Next to our building was the playground of an elementary school, though the school itself was across the street.

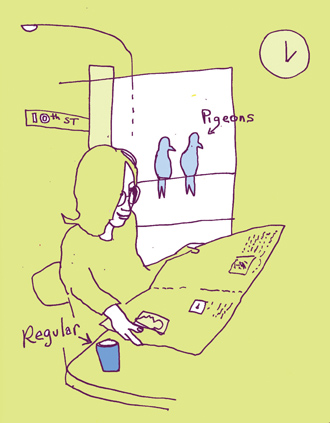

Packer: The first apartment that was mine alone was on West 10th Street in Manhattan––right in the heart of Greenwich Village, on the same block as the wonderful, quiet, literate bookstore Three Lives, where I stopped to browse 2-3 times per week; and the fabled gay bar the Ninth Circle, of which I was less aware, except at closing time (4 a.m.) when the party would spill raucously onto the street. Balducci’s, the now much-mourned food emporium, was two blocks away, and I bought more than my share of pasta salads there, and expensive pears. This was in the early 80s, and the foodie movement didn’t really have a name yet, but it was thriving on the corner of 6th Avenue and 9th Street. The other part of the immediate neighborhood that I remember vividly is the Greek coffee shop where I bought coffee every morning on my way to the subway. There’d be a line of 10-15 people at all times, but it moved quickly, and within minutes of arriving it would be my turn. “Regular coffee” was my order––this meant coffee with a specific but indefinable amount of half-and-half: more than there would be in “dark coffee” and less than in “light coffee.” I’d never asked for coffee that way before, and never have since. I guess we add our own half-and-half these days, saying “Coffee with room for cream” or even just “Coffee with room,” to keep the word count low and the line moving at Starbucks.

Cohen: I was all but panting with the desire to play grown-up. That’s what it felt like: I was twenty, fresh out of college, desperate to put on the clothes of independence. What to do? It was a bit like that folk song: “When I first came to this land, I was not a wealthy man. So I got myself a farm; I did what I could.” Well, I got myself a job; I did what I could. That turned out to mean working at the African American Studies department and renting an apartment for $340 a month.

Ferris: I didn’t have much choice in the matter, though I don’t have many complaints. The smoking, as I’ve mentioned. But in general, the landlord was solicitous, the neighbors were supportive, the area of town secluded and warm, and there was ample space to grow.

Mattison: I was in graduate school at Harvard, studying English literature and working as a teaching fellow. I’d been living in a series of university-owned buildings in which a bunch of women would each have her own room but share a living room, kitchen, and bathroom. At the end of my third year, four of us from the house decided to rent an apartment together. We wanted more independence than we had with the university as our landlord, we enjoyed one another, and I think we were ready to get past enforced friendliness with whoever else happened to be in the house with us.

Packer: There were some definite disadvantages to this apartment, probably the most significant of which was that it was a fifth-floor walkup, no elevator. But it had exposed brick walls and a working fireplace, and across the air shaft an apartment with a kitchen I could see into at night, to admire my unknown neighbor’s collection of tiny painted animals, arrayed on every available shelf and ledge. It was in a great location, I could afford it––those were reasons aplenty to rent in Manhattan.

––What was the worst feature of the apartment?

––What was the worst feature of the apartment?

Cohen: The worst feature was also the best, and that was the loneliness that seemed to breathe it. I had almost nothing with which to appoint the three rather generously proportioned rooms. In the kitchen, I took a door from its hinges and laid it on milk crates: that was my table. In the corner room, I spread a futon on the floor by the three large windows: that was my nest. In the middle room, I put my computer on another milk crate, and a cushion on the floor in front of it: that was my desk. I had no television, little money, no friends. I lived on peanut butter crackers, apples and milk. The time I spent drifting through those rooms, alone with my thoughts, was both maddening and glistening.

Ferris: They refused to give me a full year’s lease.

Mattison: The worst feature of our apartment—which was rickety but spacious and convenient, with four bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and a bathroom, all off a long hallway—was that it needed to be renovated when we rented it in June, and when we returned in September, the renovation of the bathroom was just beginning. During the whole month of September, while we scrambled around trying to teach and write and study, we had a series of workmen invading the bathroom from early in the morning until night on weekdays, and for much of the month we had no shower. I remember walking into a friend’s party and asking her if I could please take a shower. After a while my roommates and I talked about nothing but bathrooms. The nearest bathroom in a public building was blocks from our apartment, and we’d trek there in the morning, or take our toothbrushes and head for the library. Of my three roommates, the boldest and most elegant, Renie, perfected the art of dressing up in heels and nylons and quietly entering the school across the street to use the teacher’s bathroom there. Meanwhile, a friendly but painstakingly slow series of old-world craftsmen of various nationalities glued tiles on the bathroom floor, one by one, and installed slightly nicer fixtures than had been there before.

We complained to the landlord, but it didn’t help. We’d barely noticed the landlord’s name when we rented the place, but we belatedly realized that he was a lesser member of an old, distinguished Massachusetts family. His brother was the governor, and his mother was a bigshot at the UN, and his ancestors had been around for centuries. At the end of the month we had a decent though ordinary bathroom, and we felt we should pay less rent or no rent for the month, but the landlord—though we’d learned he was on the Fair Rent Commission—insisted. Renie put on her high heels again and consulted a lawyer, who said, “You mean you girls [he may even have said ‘You little girls’] intend to take on the Xs of Massachusetts?” We gave up and paid the rent.

Packer: Pigeons roosted on the ledge outside my bathroom window. This window looked onto a grimy airshaft, and the pigeons were there at all times, sighing and twittering and emitting a stink that made it absolutely impossible ever to open the window. They were, in a word, gross.

––What is your outstanding memory of the apartment?

––What is your outstanding memory of the apartment?

Cohen: I slept with the windows open. I liked the city sounds, the voices in the street, the sirens well into the night. In my memory, the windows were huge. They extended up nearly to the ceiling and came down almost to the floor. One windy night, the cross breezes churned up so wildly they lifted the covers right off me. Up they’d go, the covers, hovering a good quarter-inch above the surface of my body; then they’d settle once more. Over and over, the wind made this dance, made the pale sheet and the thin blanket levitate in the darkness and float back down. I lay awake a long time, enchanted.

Ferris: All the kicking. I’ve never found another place like it for all the kicking.

Mattison: My outstanding memory is of the pleasure of living with those three women. The apartment itself was nondescript, but I do remember cockroaches in the kitchen. I also remember the playground of the nearby school, which was under my window. I’d be awakened by the shouts of children, and I’d watch them. The littlest ones chased one another like puppies, randomly, running in one direction until something made them run in another direction. They were so different from graduate school!

Packer: I lived there for five years, so I don’t think I have a single outstanding memory. Two images come to mind: I’m sitting at my little gate-leg table and reading the vast Sunday edition of the New York Times, always in the same order: Arts and Leisure first, then Magazine, then Book Review. I must’ve done this two hundred times. The second is cooking in the tiny kitchen. There was only just room to turn around from the stove and sink and chop or stir something on the butcher block cart I’d installed. But I threw my first dinner parties in that apartment and I remember assembling multi-course complex dinners in that kitchen, despite having to put the dirty dishes on the floor sometimes to make room for my work.

––How did your tenancy end?

Cohen: The loneliness, the self-made loneliness, began to unnerve me. My slide into an almost monkish existence came to seem like it might be an unhealthy indulgence. I picked up and moved to Brooklyn.

Ferris: In tears, heartache, superstition, anguish and death.

Mattison: At the end of the academic year, all my roommates got married. I wrote a poem I didn’t show them, of which the first line was “Three roommates had I, and they all got married. . . .” We were bridesmaids in one wedding in Kentucky, and we all went to the second one in New Jersey, but I was spending the summer traveling in Europe—which cost almost nothing in those days—and I missed the third. As they announced their engagements, one by one, I felt a little strange, but only a little. In the fall I rented a studio apartment of my own, a block away. and finally lived alone.

Packer: I let go of the apartment when I decided to leave New York and enroll in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Much of the furniture wasn’t worth trying to move, so I got some friends to help me carry it down to the sidewalk. When we went back downstairs a little while later, every piece had been taken––by some recent arrival, I’d like to think, furnishing her first apartment.