Santa Suits: McCormack’s Holiday Fashion Column

13.12.05

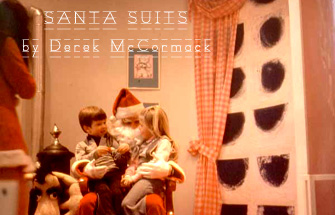

At Christmas, my parents pull out a picture. Me, sitting on Santa’s knee. Bawling. Santa’s skinny. His suit’s saggy and orange. It wasn’t machine washable. He machine-washed it. The photo’s from a department store in my hometown. I was five years old. I believed this man was Santa Claus. Now I think: Santa was a hack.

At Christmas, my parents pull out a picture. Me, sitting on Santa’s knee. Bawling. Santa’s skinny. His suit’s saggy and orange. It wasn’t machine washable. He machine-washed it. The photo’s from a department store in my hometown. I was five years old. I believed this man was Santa Claus. Now I think: Santa was a hack.

If only it had been Santa Victor. Santa Victor has a slew of Santa suits. In his closet: a red coat ornamented with gold braid and scores of antique brass buttons. Vintage black patent buckled shoes with Cuban heels. Stockings striped with candy-cane colours.

Santa Victor designs all his clothes. Has seamstresses sew them. It’s Christmas couture. Yves Santa Laurent.

In old Europe, St. Nicholas was a religious figure, patron saint of children. And pawnbrokers. And perfumers. A skinny, stern saint in long robes and mitres.

But not in North America. Canadians knew St. Nick from a poem, “An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas,” Clement Clarke Moore wrote in 1822. Clarke made him jolly, jelly-bellied, more elf than man. “He was dressed all in fur from his head to his foot and his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot.”

What kind of fur was it? What colour? Where did he get it cleaned? Moore didn’t say. An 1837 painting depicts a scene from the poem. Santa’s short, sinister. In a fur cape, brown pants and a navy-striped jacket.

The look never caught on.

In 1863, during the American Civil War, Santa got a make-over from Thomas Nast, an illustrator for Harper’s magazine. One illustration has him dressed in garments borrowed from Uncle Sam: a fur-trimmed, star-spangled coat, striped trousers.

In 1863, during the American Civil War, Santa got a make-over from Thomas Nast, an illustrator for Harper’s magazine. One illustration has him dressed in garments borrowed from Uncle Sam: a fur-trimmed, star-spangled coat, striped trousers.

When war ended, Nast put Santa in fur union suits. They came in brown, black and green. Santa wore them skin-tight, accessorized with patent pilgrim shoes. A tasselled hat. Holly sprays. It was Nast who first depicted Santa residing in a palace at the North Pole. An 1866 Harper’s illustration shows Santa spying on children with a telescope. His palace is made of snow and ice, ideal for storing furs.

“Thomas Nast was an observer of Parry and Franklin and other early Polar explorers,” Santa Victor explains. Franklin died in the Arctic in 1847. Parry, in Germany, in 1855. “Perhaps that’s where he got that look.”

Santa Victor wears red velveteen. Fun fur furbelows. For now. “I use fun furs ranging from short to medium to long shag,” he says. “Perhaps real fur will become acceptable again, and when it does, I’ll use that.”

Santa in furs.

Santa in short pants, argyle socks.

Santa in a tam, a capelet on his back.

Santa in a black oilskin coat with a black floppy hat.

I’m looking through ads in the Montreal Gazette. Old issues from the end of the nineteenth century. Santa’s depicted in a slew of styles.

Among the ads, an ensemble stands out: a suit with fur trim, black boots, and a broad black belt about the belly. Belt buckle big as a photo frame. Who created this suit? Who knows. But it cropped up with frequency across Canada and the States. In catalogues, on greeting cards. In colour cuts, the suit was scarlet. It became ubiquitous. “The orthodox costume,” a newspaper called it.

So why did the red suit stick? Cultural critic Karal Ann Marling calls it a “highly decorated business suit.” It appealed, she argues, to an American sense that Santa was a businessman, an entrepreneur overseeing a successful toy factory. I don’t know if that’s true. What I do know is Santa’s a winter. Scarlet suits his complexion.

“The early department store Santas took their costumes out of tickle trunks,” says Santa Victor, “or what the store had lying around for them to wear. Ads and promotions in the early days were usually local in nature, and as such there was no standard look,” Santa Victor says. “That’s why perhaps you see a wide range of outfits, from fur coats to tuxedos. It took Coca-Cola’s international marketing campaign in the early 1930s to give everyone a standard Santa look.”

Haddon Sundblom drew Santa for Coke. Santa, to Sundblom’s mind, was a big man—big, broad, and burly. “I prefer the look of Norman Rockwell’s Santa,” Santa Victor says. “He’s an elf, not a human. It’s more true to who I think Santa is.”

By the late nineteenth century, Canadians were dressing up as Santa. Surprising their kids, amusing church groups. Most men didn’t own scarlet suits. They put on togas, swaths of red felt or muslin tied at the waist. Boots were bolts of black oilcloth wrapped around shins. Any trousers would do.

Some Santas wore red bathrobes. Some wore whatever. “We heard a great noise, and the boys, they said it was old Santa Claus come,” said a Blackfoot boy in a letter to the Calgary Herald in 1894, “and we all ran out and there he was coming over from the Mission house with a long white beard, and a dress like an old woman, and a bundle of things on his arm and we all laughed at him ….”

“To make a Santa Claus costume is quite easy, inexpensive and creates endless fun,” wrote Mrs. E.F. Ashby in Farm and Ranch Review in 1928. Mrs. Ashby lived near Edmonton. She recommended buying red flannel, white buttons, and scarlet thread. All other costume components, she said, “may be had for the making.”

The coat. Mrs. Ashby patterned hers on a man’s dressing gown. She cut it large, so it could be stuffed with pillows, or worn by men of varying widths. The tuque she stitched from scraps. Ditto the stockings.

“On our farms are wild rabbits which are now turning white,” she wrote. A Santa suit required seven skins, fat and meat removed. Preferably tanned. “Trim off the ragged edges (the tail and legs) and with a sharp knife carefully cut the skin into a long strip.” Strips adorned cuffs and cap. A single skin was used for a collar.

In 1915, a Prairie newspaper printed a recipe for readers—a simple solution: alum and water. The solution wasn’t pricy, wasn’t poisonous. It fireproofed fabric. “The use of this solution is a safety measure which should be employed for pageants, carnivals, and receptions … and as a safeguard at all amateur Christmastide and New Year displays.”

The alternative could be agonizing. In 1905, a teenager in Victoria dressed up as Santa for her high school holiday pageant. Her robe grazed a candle. Students stampeded. It took her teacher minutes to smother Santa’s suit. In 1929, a union of travelling salesmen sponsored a pageant for Winnipeg children. Santa lit a smoke while waiting to go onstage. His beard caught fire. Fire spread to the suit. Flannel burned fast, fur trimmings took some time. Spectators tore off the costume. Santa was sent to hospital suffering burns to his face, legs, arms, torso, and hands. He survived. Scarred.

According to Santa Victor, the first professional Santa suits became available in the 1930s. “Charles Howard was the first department store Santa,” he says. Howard had trouble buying quality Santa suits, so he started the Santa Claus Suit & Equipment Co. The first firm specializing in Santa suits, red velvet with real rabbit furbelows. He sold them to students of his Santa school. He sold them to Macy’s. Santas sported them during Macy’s annual Thanksgiving Day Parade.

“Some of those suits still survive,” Santa Victor says. Santa Victor relishes comparisons between himself and Howard. Like Howard, he makes expensive suits. Expensive but enduring. Like Howard, he sells accessories—spectacles, with or without prescriptions; double-stitched toy sacks; hand-stitched stomach pads. Shabby Santas stuffed pillows in their coats. The swankiest suits had inflatable rubber stomachs sewn into them.