Success is not an Option: Postmodern Crime and Comedy in L.A.

07.05.10

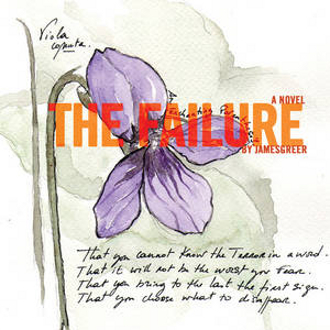

The Failure

James Greer

Akashic Books

220 pages

$15.95

Guy Forget––careening across Larkin Heights in a stolen Mini Cooper––suffused with bloodlust and baring a grin full of teeth, failed to hear the polyphonic belling of his cell phone.

The opening sentence of James Greer’s neo-noir, The Failure, published in March of this year by Akashic Books, is crammed with information. There’s the protagonist with the Paul Auster-esque name, both pulp-sounding and ontologically loaded; the absurd image of a Mini Cooper doing something other than look adorable; the schizoid description of Forget with murder on his mind and a smile on his face; and the homophonic pairing of “belling” and “cell phone” that turns an everyday irritant into something elegant. There’s so much going on, the hilarious central image––a clown car tearing down the road––almost gets lost in the shuffle.

Greer lays all his cards on the table. Each new chapter is announced with a descriptive chapter title that does much of the heavy lifting. For instance, the first chapter is called “How Guy Forget Ended up in a Coma” revealing Forget’s fate from the get-go. The story’s plot hinges on his disastrous decision to rob a Korean-owned check-cashing establishment, which is truncated as “the Korean check-cashing fiasco.” The narrative follows a linear structure, but the chapters are all out of sequence, so the reader comes to depend on the overly verbose descriptions to orient herself in the story. Greer realizes how heavy-handed this is, and provides the occasional meta-fictional wink:

What Guy Needed and Why: In which the Not Entirely Omniscient Narrator Explains the Korean Check-Cashing Fiasco and Its Inciting Incident, about Two Weeks before the Actual Fiasco. For those interested, Guy Is Sitting on the Couch in His Apartment, which the Reader Will Never See Again and So We Will Not Bother to Describe It.

Guy Forget is a harebrained scheme addict of the highest order. He doesn’t just cut corners, he slices them off with lasers. Instead of going from points A to B, Forget concocts an easier, faster route. Arriving at the alternative, however, requires an investment that far exceeds the effort it would take to follow the original path. Forget’s motivation for robbing a check-cashing joint is to fund the prototype of a new kind of “subsensory advertising” that uses possibly nonexistent and most likely illegal technology to influence consumer decisions without their being aware of it. That this will make Forget insanely rich is a foregone conclusion; but he needs $50,000 to kick-start his company, Pandemonium, Inc., into the stratosphere.

It matters little that the reader knows the outcome from the onset, for the caper’s irregular course is fueled by Forget’s astounding capacity for self-delusion.

Money, as a thing itself, does not exist. It’s an extended metaphor for a complex system of commodity exchange. Thus, to think of money as “belonging” to someone or something is a pathetic fallacy, in the literal sense. It’s our jobs, as stewards of the language, to liberate money from its normative bounds.

Obviously, Forget is not your typical bandit. After all, what kind of “criminal” employs a stolen Mini Cooper as a getaway car?

Forget’s “gang” consists of a cast of characters of the only-in-L.A. variety: his love interest, Violet, the femme fatale with a libido stuck in overdrive; Forget’s nemesis, Sven Transvoort, a wealthy programmer-playboy who is far more successful at the former than he is at the latter; Forget’s brother Marcus, a professor of “quantum photodynamics,” who refuses to come to Guy’s aid until it’s too late; and Billy, Guy’s best friend, drinking buddy, and somewhat-reluctant partner in crime.

Their friendship is the book’s most important relationship, and the ways they betray one another is the key to what Greer is trying to accomplish. Incredibly, Billy is even less clueful than Forget, which makes the simplest task an adventure. The chapters that feature the two, usually set in a bar, are laugh-out-loud funny, and call to mind the dumb-and-dumber literary high-jinks of Patrick DeWitt, Sam Lipsyte, Tony O’Neill, Jack Pendarvis and Jerry Stahl. Consider the following exchange, which occurs after an argument between the two friends:

––I mean, I’m sorry. I said I was sorry. Nothing else I can say will help. I should never have called you a… well, it’s no good repeating it, is it? The more you say, “A duck shits out more brains in five seconds than you’ll ever hold in your peanut-sized cerebellum,” the worse it sounds.

––You said baby duck.

Amidst the hilarity, there are a few flat notes. Greer, a musician who frequently writes about Guided by Voices, a band to which he once belonged, works in the occasional musical anecdote that feels out-of-place in the otherwise feverishly plotted book. Forget even composes a song shortly before slipping into a coma. Because of the novel’s frenetic structure, these scenes don’t disrupt the story. What’s a mystery without a few red herrings?

Ultimately, Forget is a conman whose skewed approach to conning others succeeds in fooling only himself. As a result, we see in Forget what he can’t see in himself: a fundamental earnestness that no amount of cynicism can ever stamp out. Guy Forget was born to lose, but who isn’t?

“There was only one flaw in the system, and that flaw, as with all flaws and all systems, was human.”

_______________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Jim Ruland’s short story “The Lever”

Sex and Micro-Prose: Trinie Dalton on Kevin Sampsell and Joanna Ruocco