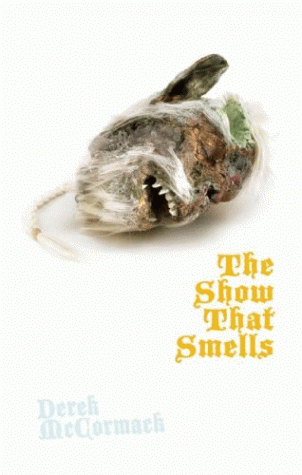

The Show That Smells by Derek McCormack

16.12.09

Derek McCormack’s books should come with a warning label:

Derek McCormack’s books should come with a warning label:

"Rising stars of country western beware! Derek McCormack is watching you. He’s making plans—fabulous, diabolical plans to kidnap, drug and in all likelihood sodomize you under the guise of ‘management.’ He’ll lull you into a false sense of security … perhaps invite you to his studio where he’ll perform grotesque procedures aided and abetted by those nearest and dearest to your poor bumpkin heart."

This detailed advisory would appear only on copies sold/purchased in Nashville and Austin, places where the next Hank Williams or Jimmie Rodgers might hit it big. Surely a public debate will rage –– critics will cry foul, citing censorship and freedom of speech, while authorities will retort that the label is a necessary precaution for the public safety.

His supporters will say, “Listen, you’ve got it all wrong. There are two Derek McCormacks—one is a highly acclaimed Canadian author/auteur; the other is his often sinister alter ego, also named Derek. The Derek of fiction is despicable. The Derek of real life is harmless (probably). He’s like David Sedaris with more Kewpie dolls and pathetic carnival freaks.”

OK. We’ll bite, but damn if McCormack doesn’t do a bang-up job playing puppeteer to a cast of characters straight out of any red-blooded American’s nightmare. In his fourth release, The Show That Smells—his latest in Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery series—McCormack continues to construct realities just south of the ones we recognize.

He deftly suspends the reader’s disbelief by using as few words as possible to establish his premise. His prose flows like poetry: a sequence of statements, almost like stage directions, at times choppy like Frank O’ Hara delivering lines about the day Lady died. In Dark Rides, McCormack writes:

“My room was a bed, a chair, a closet. A barred window. Streetcars sparked past in the night.”

In his first two works—now available in one collection, Grab Bag—McCormack applies his brief, poetic style to stories that look inward and tap his fascination with particular time periods. The characters’ experiences growing up gay in the 1950s or during the Great Depression are for the most part plausible. Alternately humorous and horrifying descriptions of “Derek” taking advantage of an open-minded friend or a homophobic redneck pulverizing a young man’s anus with a crowbar aren’t more than a stone’s throw from the realm of nonfiction.

Beginning with his third novel, The Haunted Hillbilly, McCormack explores his interest in high fashion, vampires, B-movies and Grand Old Opry headliners and The Show That Smells picks up where Hillbilly left off, returning to a dimension where haute couture vampires pursue country legends with tunnel-vision bloodlust. In the second of a promised three-book series, McCormack pits Jimmie Rodgers, his devoted wife Carrie and The Carter Family, against an undead version of Elsa Schiaparelli, famed designer largely credited for inventing hot pink. He rewrites history by embellishing on her claims to pop-culture infamy, turning a professional rivalry with Coco Chanel into a bitter battle of good versus evil, right down to their signature perfumes: Chanel No. 5 acts as holy water while Schiaparelli’s Shocking has the opposite effect.

It’s as if we’ve entered some strange sitcom where Fred Savage has been replaced as narrator by a celebrity journalist who’s all buddy-buddy with a bunch of narcissistic vampires. These undead divas lust after movie stars and country legends. They want to do them and eat them. They want to be them. The villains are always clever; the “heroes” a bit dim. Like Hank and his ladies, or the Jimmie Rodgers in The Show That Smells, they expect that because they are good they will ultimately have the upper hand, but all along the reader just wants them to give into the impeccably dressed dark side.

Or do we?

McCormack does a fine job messing with our heads. In The Show That Smells, he enhances his minimalist prose by experimenting with repetition and symbols. Each new scene starts fresh with a pattern:

“Jimmie Rodgers.

Carrie Rodgers. Jimmie Rodgers.

Carrie Rodgers. Jimmie Rodgers. Carrie Rodgers.

Jimmie Rodgers. Carrie Rodgers. Jimmie Rodgers. Carrie Rodgers. Jimmie Rodgers. Carrie Rodgers. Jimmie Rodgers.

Jimmie Rodgers and Carrie Rodgers and me in a Mirror Maze.”

The pattern shifts, evolving into an algorithm that propels the increasingly surreal, sexualized narrative. The pattern repeats and builds and builds until up is down, down is up. We’re falling through the looking glass, buried in sequins:

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

McCormack weaves an intoxicating web. Once you drink the Kool-Aid moonshine and wholeheartedly embrace McCormack’s world, his sense of gory whimsy is infectious. Reading him is like purchasing a ticket to the fun house or the house of horrors—either one, it’s all the same. He is a commanding ringmaster of an imagination run wild.

The landing page for Schiaparelli.com starts with a voiceover of the designer: “What would I like to be in another life, if that could happen?”

What would any of us be like in McCormack’s hands?

–––––

Related Articles from The Fanzine

McCormack offers a critical investigation of Santa costumes

McCormack’s history of the sequin

McCormack on tragic Hollywood costume designer Vera West

Jamie Gadette reviews Matty Byloos’ Smell the Floss

–––––

Read all of McCormack’s Fanzine articles here. Buy his new new book from Akashic here.