Inspirational Critique: a conversation with Malik Gaines and Alexandro Segade of My Barbarian

15.02.10

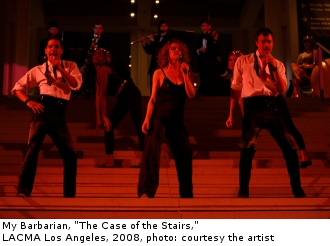

The L.A.-based artist collective My Barbarian has been creating kitsch-tinged site-specific plays, concerts, theatrical situations and video installations together for nearly ten years. Malik Gaines, Alexandro Segade, and Jade Gordon have combined their eclectic backgrounds in theater, theory, and contemporary art to create incisively intelligent work in a variety of media that encompasses references to mythology, social and political issues (both contemporary and historical), and popular culture with a sense of humor that is as biting as it is playful.

The L.A.-based artist collective My Barbarian has been creating kitsch-tinged site-specific plays, concerts, theatrical situations and video installations together for nearly ten years. Malik Gaines, Alexandro Segade, and Jade Gordon have combined their eclectic backgrounds in theater, theory, and contemporary art to create incisively intelligent work in a variety of media that encompasses references to mythology, social and political issues (both contemporary and historical), and popular culture with a sense of humor that is as biting as it is playful.

Unlike My Barbarian’s video Golden Age, which features the group booty-dancing in tricked-out sailor suits next to an equally agile audience mimicking a song and dance routine that grapples with the legacy of the African slave trade, a video clip from their Post Living Ante-Action Theater [PoLAAT] workshop at the Miami MOCA highlights one of the greatest challenges of interactive work: how to invite participation without being coercive.

The MOCA video shows a sight familiar to everyone that has ever dared to cross the threshold of inviting audience participation: a smattering of the generally enthused peppered with languid, half-hearted participants and a few stiff-lipped starers, bored in the name of culture.

Documentation is always slippery. What it cannot show are the ways that these exploratory workshops succeed, like facilitating active reflection upon participants’ positions within the field of representation promised by a democratic structure, as was the case in a workshop held during the Democratic primary, in which participants clapped their hands and publicly revealed their vote in chant form, punctuated by individual free-style justifications of their choice. Or simply creating new, multi-disciplinary connections, as a group of participants an Italian workshop in Trento did when they formed a temporary theater group that performed their own version of work they did with My Barbarian.

Collective members Alexandro Segade and Malik Gaines took the time to explain PoLAAT in more depth before heading off to Spain for PoLAAT Madrid, presented as part of ARCO’S spotlight on Los Angeles.

Fanzine: In the 1960s, many experimental theater groups saw direct, physical participation in artistic creation as a “precursor to social change.” Do you think this still holds true? In your opinion(s) what is the radical potential for contemporary experimental theater?

Malik: Theater is social change. The form is always collective, sometimes communal, occasionally communistic, and done over time. Because of the bodies that narrativize space, politics are immediately legible in theater. A history of radical leftist theater makes sense in my imagination, while histories of radical leftist visual art or music seem spotty. There’s [Augusto] Boal’s [founder of Theatre of the Oppresed] saying about theater: “not the revolution, but a dress-rehearsal for the revolution.” Of course there is a long tradition of ethical instruction in theater, and it’s not just in the 1960s or even with Brecht that politics entered performance.

Audience participation is difficult. Who wants to be compelled into someone else’s system, given false choices that prop up the spectacle, but offered nothing that really feels transformative? That’s the compulsory participation our democracies demand of us; why, even in the pursuit of realism, re-perform that? In participating, our deepest alienations become apparent to us. On the other hand, some participatory forms are very popular, like certain line-dances.

Participation should feel voluntary to the participant.

I tend to believe that acting out different possibilities for our lives can be radically transformative. I could imagine someday proving to myself that that isn’t true. But rather than imagining the 1960s as an era discontinuous with our own, lost on the other side of some major epistemological break, I think of that project as evolving.

I tend to believe that acting out different possibilities for our lives can be radically transformative. I could imagine someday proving to myself that that isn’t true. But rather than imagining the 1960s as an era discontinuous with our own, lost on the other side of some major epistemological break, I think of that project as evolving.

Alex: The Post-Living Ante-Action Theater [PoLAAT] is designed to address this question and this question is still open. While performance art has a tradition of spontaneous action presented as final work, theater is traditionally structured around rehearsal, with the goal of an ongoing but ‘finished’ product to be presented to the audience repeatedly. The structure of the PoLAAT is a series of performance workshops.

The final workshop is for a public audience, making the process visible, and I think that is the contribution made to the performers: another model for performance, one which privileges the social, temporal, spontaneous and even ephemeral, while still allowing for theatricality. It’s not social change, as such, but a proposition of a new set of priorities that includes the social in understanding what performance can do.

While the tenets of the Post-Living Ante-Action Theater do provide a means of processing, criticizing, discussing, challenging, informing and playing with the political and social and historical and contemporary, the actual effect of the workshop project is to make a space outside.

Fanzine: Do all of your works have a participatory element like the Post-Living Ante-Action Theater? How does the role of the audience change in each of your works? Similarly, how does my Barbarian conceive of spectatorship?

Alex: All of My Barbarian’s projects result from collaboration, whether simply among the three of us, or with other artists and the institutions/sites where the work is presented.

We have made performances and videos that do require, suggest or allow for audience participation, particularly Voyage of the White Widow, made in 2007 for de Appel, included in Performa 07 at the Whitney, which used play and audience participation in its unfolding narrative of Dutch sailors at the advent of capitalism, and the video The Golden Age (2007) which proposes that the viewer learn the dance routine ‘inspired’ by slavery, putting their body in a position outside subjectivity. In both cases, the work used play to bring the audience into an encounter with political and historical problems.

Participation is useful for creating a group out of an audience. In the Suspension of Beliefs performances, we get a group of people together to levitate each other. In that instance, the group is asked to ‘dis-believe’ in gravity, with the effect of making someone float. And sometimes, it works.

Much of our work is site- (or situation-) responsive. In those instances we do think of the audience as an audience, people who came to hear what we have to say, to receive us, as it were. But we do not conceive of them as the audience. There is no universal body of viewers for us. LA is not New York is not Cairo is not Vilnius. Just as we are framed by the situation in which the work is presented, so too is the audience. And when I say framed, I mean both how a picture is framed, and how someone can be framed for a crime they didn’t commit… When we make work for an audience that doesn’t speak English as a first language, we try to use as much of their language as possible within the piece. We bring people into the work who come from ‘there’ to bridge those gaps, to complicate and enrich the relationship.

Liudni Slibinai in Lithuania were my favorite example of this, as we needed to work closely with the young Lithuanian performers in order to get our ideas across, but also to understand what those ideas might mean in a place far from our own. To a certain degree, we are relating to the audience as stand-ins (surrogates?) for, or the products of, a national identity just as we, whether we like it our not, represent our own.

Liudni Slibinai in Lithuania were my favorite example of this, as we needed to work closely with the young Lithuanian performers in order to get our ideas across, but also to understand what those ideas might mean in a place far from our own. To a certain degree, we are relating to the audience as stand-ins (surrogates?) for, or the products of, a national identity just as we, whether we like it our not, represent our own.

We also relate to them as people who are interested enough in the arts to show up, and the familiarity with art world concerns, for example, can be used as a way to close some of the gaps; so there is both specificity and globality; otherness and sameness; sameness in otherness; action in the seemingly inactive role of audience; and the performers are watching the audience, too.

We are flexible with the ways in which we approach this question of the spectator – but prefer the idea of an audience, which has a performative function of its own. In any case, the audience is active in our conception. They make the performance. There is that neologism of Boal’s: the spectactor, that is, someone who watches and performs, who is active in a critical way, and may offer suggestions as to how the performance should unfold. In the PoLAAT projects, the participants are spectactors but the term sounds silly to me… Like Derrida’s hauntology, spectactor is maybe a bit too cute.

In trying to figure out what I meant by the 5th principle of the PoLAAT, Inspirational Critique, for a recent essay, I wrote this about collaboration:

Hence, a useful complication is collaboration: by undermining the authority of the signature/brand, we forge a collective identity that cannot be collected. Collaboration must be critiqued too: museums increasingly support collaborative projects and so are imbricated within these artistic productions. Everyone is implicated: artists become collaborators in an uncomfortable sense: they are working for a regime. Many artists who mobilize critique toward liberation fashion themselves the resistance, yet our circumstances are such that artists must collaborate with the establishment in order to be seen/heard.

Ah paranoia and ambivalence…

Fanzine: How has your position on the usefulness of irony as a critical tool changed (if at all) over the ten years you have been working as a collective? Any thoughts on the backlash against irony in recent years?

Malik: I’m not sure I know of this backlash. There was that moment after 9/11 when irony was declared dead by New York media, a mournful wish. But the American government/media narratives that followed were hardly unironic. To this day, my favorite Washington D.C. news sources (other than the very literal radio program “Democracy Now!”) are a snarky blog called Wonkette and Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show. Their irony frames a criticality that is quite effective.

Maybe there are some critical strains now against irony? There are certainly curators and scholars who prefer not to make jokes. But there are others concerned with play, others thinking about the creative dissonances of transnational experience, others still theorizing queer aesthetics; all of these must contend with the critical distances irony opens up.

Alex: Part of the reason I am allergic to the notion of ‘irony’ as something that can be either ‘in’ or ‘out’ is that what people mean by it is unclear to me. Irony, strictly speaking, is a literary device. Like most rhetorical forms that are adapted for use in art discourse, its use becomes tied to very specific aesthetics, and the danger is that the meaning gets lost in the (market) exchange of ideas/buzzwords/memes. This has happened with metonymy & metaphor too…

What does irony look like? I’ve never seen irony. There’s that Alanis Morissette song where she describes a series of situations that she calls ‘ironic’ but which are, in fact, more like, ‘inconvenient.’ The fact that a song about irony is not about irony is ironic. That song is from the 90s and may be to blame for the backlash?

Yes, and picking up what we started in another email, the move to ‘sincerity’ is pretty insincere. So, it’s ironic.

As you noted, there is no dichotomy between the ‘sincere’ and the ‘ironic,’ unless you simplify both terms to mean the least of what they can: sincerity is meaning what you say, and irony is implying a distance between what is said and what is meant. But it wouldn’t take long to see how one can be sincere in their irony; and vice versa.

What interests us within this flawed structure is that it clarifies the sense that the excess of dichotomies are interesting and productive. Ambivalence may turn out to be the place to be. Or maybe not…

One reason that people may get us confused on the fake ironic-sincerity chart is that camp, with its melancholic relationship to the past (sincere?), and its dead-pan alienation from the defunct structures it claims (irony?), is confusingly culturally specific, slippery, wrongful and infused in our every gesture.

If we are going to implement literary devices to describe what we do, I would like to point to the use value of puns and rhymes, two technical feats of language that we use all the time because they are about bringing ideas together through arbitrary, potentially absurd, but nonetheless motivated, connections, which make meaning in meaninglessness and help us remember the words.

Fanzine: What’s next for My Barbarian?

Alex: Literally, PoLAAT Madrid, which begins February 8th at El Matadero Madrid / ARCO.

After Madrid, we are doing projects in San Francisco MOMA and MOCA in Los Angeles, both of which will be about how these institutions function, from the P.O.V. of the personnel who work there. We are re-presenting The Night Epi$ode as a project at the Hammer Museum this summer/fall 2010. There’s other stuff like that, so to a certain degree, the answer is: continue.

We have some teaching jobs, together and apart, and I have been working on a project outside the group, a series of performances which address the battles over gay marriage in California through a science-fiction allegory. The first part premiered at LAXART last week.

I would like to answer this question more broadly, but like a troupe of strolling clowns in a herky-jerky wagon, it is always hard for us to see over the next hill.

After ten years of collaboration, with the last five being prolific, a large part of what we have to do is archive the work. Before we are finished doing this, we have some dreams that should be un-deferred.

But I know that when this is over, I will be left with some regrets no matter what.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

We Was Voodoo: a Conversation with Karsten Krejcarek and Matthew Ronay